What’s with all this consort union in Tantric Buddhism? No, it’s not about sexual fantasies. The psychology of Yab-Yum consorts, union of wisdom and compassion

Tibetan Buddhism is above all practical. In Vajrayana, practice, practice, practice is the mantra of progress. Practical means, step-by-step progress, and that means daily meditation involving body, speech, and mind, in the form of mudras (body), mantras (speech) and visualization (mind). By involving all three, progress is rapid, particularly by involving mind with complex visualizations with deeply meaningful symbols designed to trigger subconscious revelations.

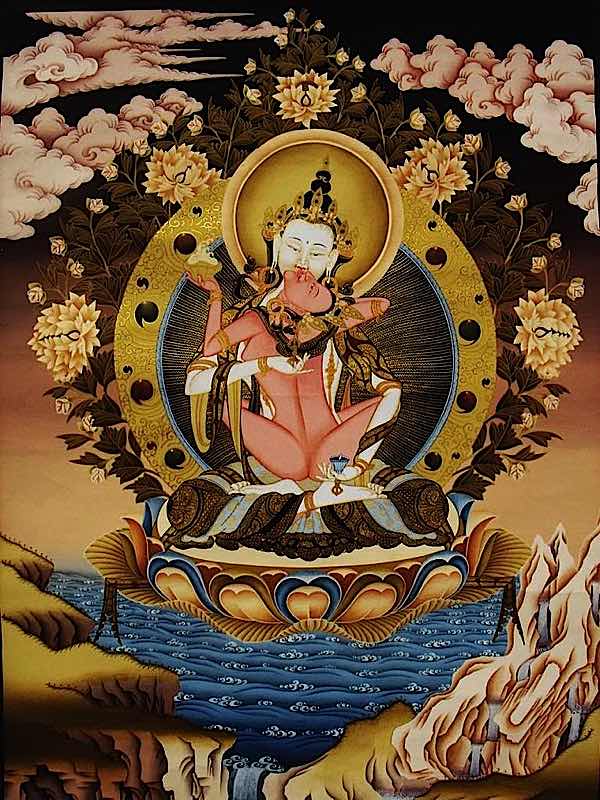

The concept of union — union of wisdom and bliss — is represented by Father (compassion) and Mother (wisdom) in intimate union. A simple handshake wouldn’t be symbolically up to the task of conveying “union as one.” Yet, sometimes, those visual metaphors are misunderstood — and even lead to controversy.

Historically, as little as a few decades ago, when British explorers first arrived on the Tibetan plateau, they were shocked by all the sex they saw displayed in Buddhist temples. They were quick to brand Tibetans primitive, shamanistic or Demon-worshipers. Until the seventies, this contempt for Tibetan Buddhism continued — except amongst a growing group of Western students. Instead of understanding the profound symbolism of Karuna (compassion) and Prajna (wisdom) in perfect union, many saw only lust.

Words versus symbols

Western culture tends to lean towards the expression of ideas in words; eastern cultures tended more towards images as metaphor. Even Chinese calligraphy is image-based. Ultimately, Tibetan Buddhism teaches the language of the mind, which is visual metaphor and symbol. The most famous symbol in Mahayana Buddhism is the lotus, a flower that grows in the filth (muck) but emerges from the waters in a burst of glorious floral perfection. The lotus symbol speaks more than a book full of words: it’s a symbol of our own Buddha Nature emerging from the obscurations of our current lives; it is a symbol of compassion; ultimately, it has many hidden meanings as well.

In part, words are inadequate to the task of teaching Buddhism by their very nature: they are “labels” — which is discouraged in Buddhist philosophy. Labels give rise to attachments and cravings. Labeling one thing “good” and another “bad” leads to coveting the “good” and “avoiding” the bad.

Attachment to labels

Attachment to “labels” go to the very heart of Buddha’s teachings on the Eightfold Path. The great Tibetan Buddhist teachers — instead of trying to describe with words — expressed using visual symbols recognized by the mind. In theory, symbols convey with more precision than words. Union of mother/father becomes:

- the union of compassion (male) and wisdom (female)

- skilful means (male) and insight (female)

- relative truth (male) and ultimate truth (female.)

Even in written form — as with elaborate spoken sadhanas used in practice — the teaching was still visceral and visual. A sadhana (words) would be largely a very detailed description of a visual symbol, down to the colour of hair, the expression on the face, and gesture of the hands, and the many specifics of the background mandala.

Not carnal — inspired by practicality

The horror some Westerners felt, before the liberating sixties (or even today), might have had to do with overall prudishness, puritanical zeal. This is also the reason why the Dalai Lama famously advised teachers not to openly discuss these higher visual practices, except with students who received teachings, due to the likelihood they would be misunderstood. In part, this is the rationale behind empowerments and teachings and authorization.

Unfortunately, along came the internet, and it was too late to “hide” images that might be misunderstood. Now, all teachers can do is explain them. Similarly, mantras were freely published on the internet — without accompanying teachings.

Back in those days, especially before the liberal 1960s, sex just wasn’t talked about in the west. To the people of Tibet, sex was just a function of life, and it was also a reasonable non-ambiguous symbol of union — therefore, a highly practical visual symbol. Even in the sexually liberal sixties, when Buddhism flowered in the West, Vajrayana was still “exotic.”

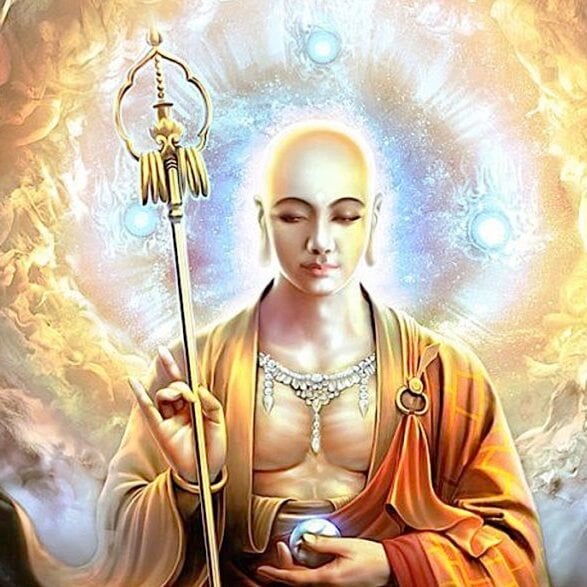

Yab Yum means Father Mother

Deities visualized in consort union are Yab Yum. Yab means literally “father” and Yum means literally “mother.” This gives a sense of the concept of YabYum as a higher emanation of Buddhas — it’s the highest of visualized practice, Highest Yoga Tantra — because it is a complete visualization combining the Enlighted Compassion and Wisdom as Father and Mother, not just one, or the other.

In Tibet and other countries where Vajrayana flourished, even monks and nuns — who renounced sex in the same way they renounced any other craving or attachment (including food) — would not have felt arousal from the symbol. It is true, that in Highest Yoga practices, the notion of “bliss” is important — clear light and bliss — but here again sex is a precise metaphor, since the pleasure of sex is instantly recognized as “blissful” (therefore, the mind instantly recognizes it), and not carnal. These images did not encourage rampant sex; they merely conveyed a clear message.

The transformative symbol — transforming ordinary appearances

The key difference between Mahayana Buddhism, and advanced Tantric practices is the objective of “transforming ordinary appearances.” Vajrayana is advanced Mahayana, and includes all the sutra-based practices; then, adds advanced visualization practices designed to help the mind transform.

So, in addition to being a symbol of the union of compassion (male) and wisdom (female), the symbol is also an expression of transformation. In Tibetan Buddhism, the transformation is a key practice. We try to transform our incorrect perceptions of the “real” world and open the way for intuitive, wisdom perception.

There’s also a sense of “union” with the divine (which is ultimate clear light or realizations of Emptiness). As psychologist Rob Preece explains:

“…an intimate union with the divine… We sense the potential of totality that is only possible through this union, but fail to recognize that this is an inner experience, not an external one. Animus and Anima are known as the Daka and the Dakini in Tantra.” [1]

Images that prejudice

As late as 1959, Richard Nixon (then Vice-President) reportedly refused to consider helping those Tibetan “Demon-worshipers”— this apparently because he saw an image of Yamantaka with consort. Of course, the symbolism of Yamantaka is wrathful compassion — as the foe of death — in union with his wisdom consort.

In 1962, this reputation persisted, when in a book titled Buddhism, Christmas Humphreys wrote: “Nowhere save in Tibet is there so much sorcery and ‘black’ magic, such degradation of the mind to selfish, evil ends.”

Later, as refugees from Tibet migrated around the world, the perceptions changed from “primitive and demonic” to “compassionate and wise.” How could this perception so radically transform, and so quickly?

The perception changed because, instead of judging from words in a book written by Victorian scholars, we experienced compassionate wisdom first hand — exemplified in teachers such as the his holiness the Dalai Lama, Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche, Lama Yeshe, among many others.

Psychology of Union

The eminent psychiatrist Carl Jung, early on, helped clarify the language of symbols — and helped us understand the sound psychological base of Tibetan Buddhism. But, still, it was difficult to put aside the urge to unfairly characterize sexual union. In Ganpat, the Road to Lamaland (a derogatory book set in the time of the first British explorers), the author wrote:

“The Tibetans, a mountain people with the natural superstition common to all ignorant races who live under the high snows, with the terrors of gale and snowfall and avalanche ever before them, and the bleak solitude of the heights about them, inevitably come under the thumb of the Lamas, and so today the Lama is the most important person in Tibet, and the Tibetan’s life is literally one unceasing round of devil-dodging from birth to death.”

Highest Yoga Tantra symbolism

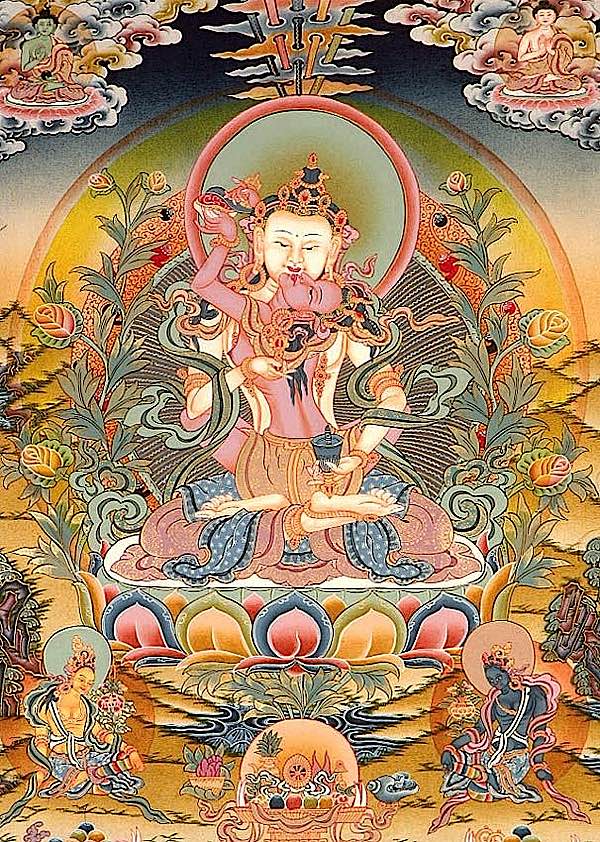

In Vajrayana, the Highest Yoga Tantra deities are “aspects” or “emanations” of Buddha. Ultimate truth — prajna or wisdom — speaks the language of oneness and emptiness of ego. In conveying this truth, instead of portraying the Buddha seated under the Bodhi tree, then “telling” us about these higher practices, the great teachers instead visualized the deities in wrathful forms (skillful means) and in union with consorts (wisdoms). Rob Preece, in his breakthrough book The Psychology of Buddhist Tantra explains:

“In Highest Yoga Tantra, the deities that embody masculine and feminine are known as dakas (Tib. khadro) and dakinis (Tib. khadroma)… In order to understand the daka and dakini, we can look in the Western parallel found in Jung’s view of the Animus and Anima and their influence both individually and in relations… In our projection of Anima and Animus we may have been beguiled into a relationship — not in the outer world, but with an inner reality… In the [Western] myth of Tristan and Isolde, Tristan falls irretrievably in love with a female figure who is not a real woman. She is like a chimera or muse. When he meets a real woman who is able to help him back to some semblance of normality, he cannot love and accept her for who she is… He is pulled so strongly to the romantic image that he chooses to return to imaginal reality…

“This story depicts something each of us years for — an intimate union with the divine… We sense the potential of totality that is only possible through this union, but fail to recognize that this is an inner experience, not an external one. Animus and Anima are known as the daka and the dakini in Tantra.”[1]

Body, Speech and Mind: three Vajras

Another reason images, symbols and activities are incorporated into Vajrayana practice is that Tantra incorporates all three of the “vajras”: body, speech and mind. Mudras and gestures are activities, for example, are body; mantras and praises and dedications are speech; meditation and visualization are mind.

NOTES

[1] The Psychology of Tantra, by Rob Preece.

More articles by this author

Mo Dice and Mo Mala, Bamboo Sticks, and other “divinations” — “Mo could prove beneficial…” HH Sakya Trizin

Lama Zopa Rinpoche and other teachers recommend Kṣitigarbha mantra and practice for times of disaster, especially hurricane and earthquake, because of the great Bodhisattva’s vow

50 Songs of Milarepa and the Grand Epic Story of Mila the Cotton Clad: Murder, Evil, Revenge, Redemption, Ordeals, Doing What’s Right

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Josephine Nolan

Author | Buddha Weekly

Josephine Nolan is an editor and contributing feature writer for several online publications, including EDI Weekly and Buddha Weekly.