Chenrezig: the many faces of Avalokiteshvara’s compassion — sometimes we need a father or mother, sometimes a friend, sometimes a warrior

Sometimes we need the gentle mother or father to guide us. We often need a best friend to console us, pat our back, pick us back up and inspire us to work harder. Or, we might need the strength of a warrior to help us. Other times we are best helped by the stern king — to get us back on track with rules and enforcement. When we are fearful, maybe we need to take shelter in the arms of our own wrathful monster — a beast other monsters fear.

The faces and manifestations of compassion, of Avalokiteshvara, comes in many forms: father (Chenrezig), mother (Guanyin or Tara), warrior (Mahakala), king (Hayagriva), or — all of these, embodied in 1000-armed, 11-faced Avalokiteshvara. These are the many faces of the Enlightened Bodhisattva Deity.

Buddha of Compassion

An Enlightened Bodhisattva Deity, by definition, IS compassion. Technically, an Enlightened Bodhisattva Deity equally combines compassion and wisdom, but to simplify, we often just say “compassion.” Metta, kindness, compassion are defining characteristics of Bodhisattvas. No Bodhisattva or Buddha is more iconic of compassion than loving Avalokiteshvara (Chenrezig, Guanyin, many other names).

“Meditating on the deity Chenrezig, the Buddha of compassion, helps cultivate a more loving, accepting and caring sense of self-worth,” writes Psychologist Rob Preece, author of The Psychology of Buddhist Tantra. [1]

What is a Bodhisattva Deity?

Understanding Bodhisattvas and Buddhist Deities for what they truly represent — more our own enlightened potential, than a supernatural being — is already a difficult topic. Why, then, do most Bodhisattvas have so many faces? Why not just settle with Avalokiteshvara for compassion? Why have dozens of Avalokiteshvaras and hundreds of Bodhisattvas? The answer lies, in part, with mind — and Buddha is known to have pioneered the deep exploration of the mind, long before science and psychology.

Noted teacher Stephen Batchelor explains the psychology: “In contrast to the approaches of conventional religion… the practitioner chooses to confront the bewildering and chaotic forces of fear, aggression, desire, and pride, and to work them in such a way that they are channelled into creative expression… and wisely engaged forms of life.” [1]

For each of these — fear, aggression, desire, pride, anger, and so on — there is an Enlightened form of Chenrezig. (Or other Bodhisattvas, but that is a different story.)

Bodhisattva’s Faces

Avalokiteshvara (Guanyin, Chenrezig), whose very name inspires compassion, is the very face of Buddha-nature — its penultimate expression. The kind face of Chenrezig is unmistakably compassionate: serene, smiling, relaxed, emitting an almost palpable energy of soothing comfort. In some countries, venerated as Guanyin (Kuan Yin) She is known by the gentle, smiling face of a caring mother. Avalokiteshvara isn’t limited by appearance, sex or other human weaknesses. He or She embodies perfection and compassion.

How, then, is it reasonable to have yet another compassionate emanation, Hayagriva, portrayed with a warrior-snarling face, a screaming horse head bursting from his skull, surrounded by flames, stomping on people with massive red feet, and embracing a naked consort Vajrayogini? Hayagriva is none other than Chenrezig in wrathful form, and his consort Vajrayogini (representing Wisdom in union with Compassion) is none other than an emanation of glorious Tara.

We All Have Buddha Nature

Diversity, in fact, is the point. When we think in terms of devotion in Buddhism, we use language like “taking refuge.” Conventionally — relative truth — we take refuge in the Three Jewels: Buddha, Dharma (the teachings) and Sangha (the Enlightened Sangha of Bodhisattvas.) Ultimately, we take refuge in our own innate Buddha Nature. “The one who bows and the one who is bowed to are both, by nature, empty,” is a popular one-line Buddhist praise.

Since every mind, amongst the billions of sentient minds, is different, clouded by different obscurations, the deity we take refuge in is likewise unique to each of us.

[See “In Buddhism, Who Do We Pray to?”>>]

Thich Nhat Hanh, the great Zen master, puts it this way: “You and the Buddha are not separate realities. You are in the Buddha and the Buddha is in you.” [2]

Rob Preece elaborates: “Our innate Buddha potential is said to be like a priceless jewel buried beneath our home, while we live our lives in ignorance of it … the intention of Tantra is to gradually awaken the seeds of our innate wisdom as a source of health, power, love, and peace that can live through every aspect of our lives. We can engage in life more fully and confidently because we are in relationship to our true nature, personified in the deity.”[1]

Psychology of Visualizing Deity Forms

The skillful method of visualizing different forms of Enlightenment is soundly based in Psychology, even though it dates back more than two thousand years in Buddhism. “The deity in Tantra can be understood as a gateway between two aspects of reality,” writes Psychologist Rob Preece. [1] “Buddhism has no concept of a creator God… The deity is not to be viewed as a god in the sense of an entity that has autonomous existence beyond human consciousness. Rather, the deity is a symbolic aspect of forces that arise on the threshold between two dimensions of reality, or two dimensions of awareness. In Buddhism, we speak of ‘relative truth’, the world of appearances and forms, and ‘ultimate truth,’ the empty, spacious nondual nature of reality.”

Visualization is a proven method of engaging mind. While breathing and focusing on mindfulness is a powerful method of contemplation, guided deity visualization is a different and proven technique. Because these are guided meditations, from great masters who have attained Enlightenment, we follow in their great footsteps. By meditating as they did, we remove a lot of wasted effort in our own quests for Enlightenment. But — these same footsteps do not work for everyone.

Many different Yidams and guided meditations were handed down through these great lineages — each the same, yet different. The elements of generation/completion and so on are contained in each. But the emphasis is different, depending on the Yidam you choose. And that’s the whole point.

Yidams in Tibetan Buddhism are translated as “Heart Bond Deities” and are tuned and aligned to an individual’s needs. An angry person might seek out Yamantaka pratice to resolve his emotions. An overly attached or sensuous person — most of us today, attached as we are to the latest consumer products — might take refuge in Vajrayogini. There is a finely tuned “Yidam” for everyone. Within the many names and faces and emanations of Chenrezig is a form for almost anyone. Here, we’ll look at a few of the most popular emanations of Avalokiteshvara, and then list some more for reference.

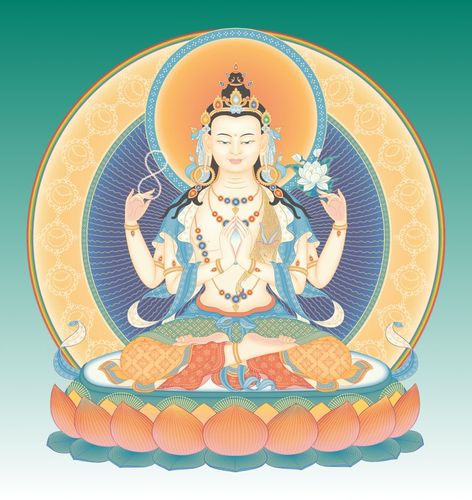

Four-Armed and 1,000-Armed Chenrezig

Avalokiteshvara with four caring arms is, perhaps, the most approachable form. The extra arms connote how busy Chenrezig is, reaching out with caring hands to compassionately help all beings. Possibly even more recognizable is the great 1,000 Armed Chenrezig (or Guanyin) — with countless arms and heads.

When missionaries first reached Tibet and Nepal, they were shocked by these 1000-armed “creatures” (and even more so by wrathful Buddha forms), labelling them demonic. In fact, the symbolism is very clearly compassion. Whether we are a missionary helping others, or a mother helping a child, we reach out with our arms to actively help people.

Unlike some other forms, notably wrathful forms, where it is advised the student seek the guidance of a teacher (to avoid misunderstandings, such as those of the missionaries above), the four armed and 1,000-armed Chenrezig or Guanyin is accessible to all. Simply imagine His (Chenrezig) or Her (Guanyin) face, and chant the famous mantra:

Om Mani Padme Hum

The mantra, and the gentle visualized face, are immediately soothing. You can feel Chenrezig’s loving arms wrap around you.

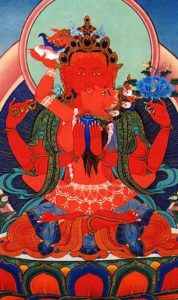

Hayagriva, the Horse-Headed

Hayagriva (Bato Kannon in Japan) is undoubtedly one of the most popular emanations of Chenrezig in Tibet and Mongolia, both horse-oriented cultures. He is also very popular because He was strongly encouraged by the great Atisha. He combines all three of Compassion (Red Hayagriva), Wisdom (Blue Vajrayogini, his consort) and Activity (of compassion and wisdom — the hero nature, represented in the green horse head.) Sometimes, He is said to be an emanation of Amitabha, the head of the Padma Family, other times he is an aspect or emanation of Avalokiteshvara — which amounts to the same thing.

He is the Heruka of the padma (Lotus family of Amitabha and Chenrezig). As a Heruka — often translated as “Hero” — His practice is a Highest Yoga Tantra practice, highly restricted and requiring permission and empowerment. This is for the protection of the practitioner, since His practice is very powerful, complex and profound — but only if fully understood.

Erupting from Hayagriva’s fierce head is one, three or more horse heads — their mouths wide apart as they scream their terrible stallion’s roar. For those who have not heard a stallion enraged, it is a frightening sound, at least as ear-splitting as a predator roar. The stallion will lay down his life for his herd, ears pinned back as he rears up, screaming, roaring and fighting to the end against an entire pack of wolves — and chances are the horse will win. The horse head, is usually green for “wind” since he is very much an action hero — action Heruka.

And that’s just for starters. Hayagriva’s own face (or faces if he has three faces) are ferocious. He has the most amazingly penetrating three eyes of any Bodhisattva. In any Thangka, Hayagriva always seems to have the most intense eyes. He is Hulk-like in body, all muscle and sinew, but then his belly bulges — symbolic of his profound inner chi and energy. The symbolism is powerful.

His concern is another Highest Yoga Tantra deity, the great Vajrayogini (Vajra Varahi) — here usually blue instead of red, since Hayagriva is himself crimsom. Their Yabyum union represents the inseparable nature of wisdom and compassion in Buddhism.

Hayagriva is a beloved healer as well, known to be aggressively powerful in stopping deadly, incurable diseases such as cancers. His power over diseases is because he overcomes all nagas.

Black Mahakala

Black Mahakala is an Enlightened Dharma Protector — however, not for the uninitiated. For general protection we might turn to Green Tara; Black Mahakala is the big gun.

Despite that, he is possibly the most popular of the wrathful Dharmapalas (or second only, perhaps, to Palden Lhamo, the great ferocious emanation of Tara). See this feature on Wrathful Deities>>

The various forms of Black Mahakala are not for the faint of heart, since one of the reasons we call on Dharmapalas is to keep our own practice on track. You can count on a “snap back” if you neglect your practice!

Again, the question arises, why does compassion take on such ferocious forms? Because we all “backslide” in our practices, we need that ferocious kick in the rear end once in awhile. When your practice (or your village, or your country) are in trouble, you want a ferocious warrior peace-keeper or a soldier on your side. The “Great Black”, as he is nicknamed, emanates unimaginable power.

The power can be used in many ways, provided you have the karma — and, that karma includes having the good fortune to have initiation — and especially if it involves removing an obstacle to practice (such as sickness, poverty or doubt):

- heal and pacify sickness

- increase life, good qualities and wisdom

- bring what is needed (including good fortune) into our lives to help overcome the obstacle of poverty or stress

- remove confusion, lack of faith and ignorance.

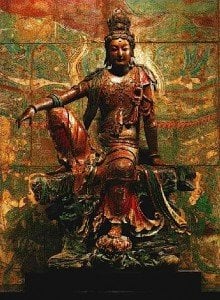

Guanyin (Kuan Yin, Kannon in Japan)

Without doubt, Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy, is among the most popular Bodhisattvas in the world, honored by countless millions. She is Avalokiteshvara. Her sutra is Avalokiteshvara’s. Her activity is compassion.

She who hears the cries of the world, is Avalokiteshvara (Chenrezig) visualized in Chan and Zen and some other Mahayana schools as Divine Feminine (except in Japan, where Kannon is mostly male). Some teachers in Tibet say that Guanyin is either Tara, or Tara combined with Chenrezig, but in China and Japan She is thought of strictly as Avalokiteshvara. Since Tara emanated from the same root as Chenrezig, it doesn’t matter. Sex is largely symbolic. In China and Japan female is associated with compassion, while in Tibet, Nepal and India, male is thought of as symbolic of compassion.

Guanyin is a Goddess, and by many is venerated in this way. Such praise and worship is not in conflict with Buddhist belief, and people born and raised with Guanyin traditions see no contradiction between Guanyin the compassionate Goddess in Samsara and Guanyin the Enlightened Bodhisattva. Just calling Her name or mantra — can bring salvation.

Guanyin is, like Chenrezig, active compassion. In the stories and legends it is Guanyin who is the rescuer, the compassionate and loving one. The rescuer role is why She is often thought of as Tara.

Guanyin, Herself, is known by many, many names herself. On top of these, She also has countless unique emanations. In other languages she is known as:

- In Japanese, Guanyin is Kannon (観音), occasionally Kan’on, Kwannon or more formally Kanzeon (観世音, the same characters as Guanshiyin) the spelling Kwannon

- In Tibetan, the name is Chenrezig or Chenrézik (Standard Tibetan: སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས).

- In Korean, Guanyin is called Gwan-eum (Hangul: 관음) or Gwanse-eum (Hangul: 관세음)

- In Thai, she is called Kuan Im (Thai: กวนอิม), Phra Mae Kuan Im (Thai: พระแม่กวนอิม), or Chao Mae Kuan Im (Thai: เจ้าแม่กวนอิม)

- In Burmese, She is Kwan Yin Medaw (Burmese: ကွမ်ယင်မယ်တော်).

- In Vietnamese, the name is Quan Âm or Quán Thế Âm

- In Indonesian, Kwan Im or Dewi Kwan Im. She is also called Mak Kwan Im or Mother Guanyin

- In Malaysian Mandarin, the name is Kwan Im Ma “Mother GuanYin”, GuanYin Pusa (GuanYin Bodhisattva), Guan Shi Yin Pusa (GuanYin Bodhisattva).

- In Khmer, Preah Mae Kun Ci Iem.

- In Sinhalese, Natha Deviyo (Sinhalese: නාථ දෙවියෝ).

- In Hmong, the name is Kab Yeeb.

Glimpsing the Faces of Compassion

The expression of Enlightenment is not limited by form, face or name. The names and forms visualized tune into our own personal perspective on Enlightened Compassion. We can’t understand, yet; our minds create our own obstacles, such as doubt, stress, fear, emotions — obscuring our Buddha Nature. The visualizations, images, names, mantras are keys and locks that allow us to gradually unlock our Buddha Nature, by clearing away the obscurations and obstacles.

In the silent moments, in mindfulness practice, or when we sit and imagine Chenrezig or Guanyin, we tap into little moments of spontaneous insight. The many faces and stories of Enlightened Compassion help us tune our internal mind-radios to a frequency a little closer to our Buddha Nature.

NOTES

[1] The Psychology of Buddhist Tantra, Rob PreecePublisher: Snow Lion; 1 edition (Nov. 8 2006) ISBN-10: 1559392630, ISBN-13: 978-1559392631

2 thoughts on “Chenrezig: the many faces of Avalokiteshvara’s compassion — sometimes we need a father or mother, sometimes a friend, sometimes a warrior”

Leave a Comment

More articles by this author

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Lee Kane

Author | Buddha Weekly

Lee Kane is the editor of Buddha Weekly, since 2007. His main focuses as a writer are mindfulness techniques, meditation, Dharma and Sutra commentaries, Buddhist practices, international perspectives and traditions, Vajrayana, Mahayana, Zen. He also covers various events.

Lee also contributes as a writer to various other online magazines and blogs.

Thanks. That article was great.

❤❤❤ Thank you ❤❤❤