Lama to All — Jetsunma Tamdrin Wangmo (1836–96) — biographical chapter from The Sakya Jetsunmas: The Hidden World of Tibetan Female Lamas

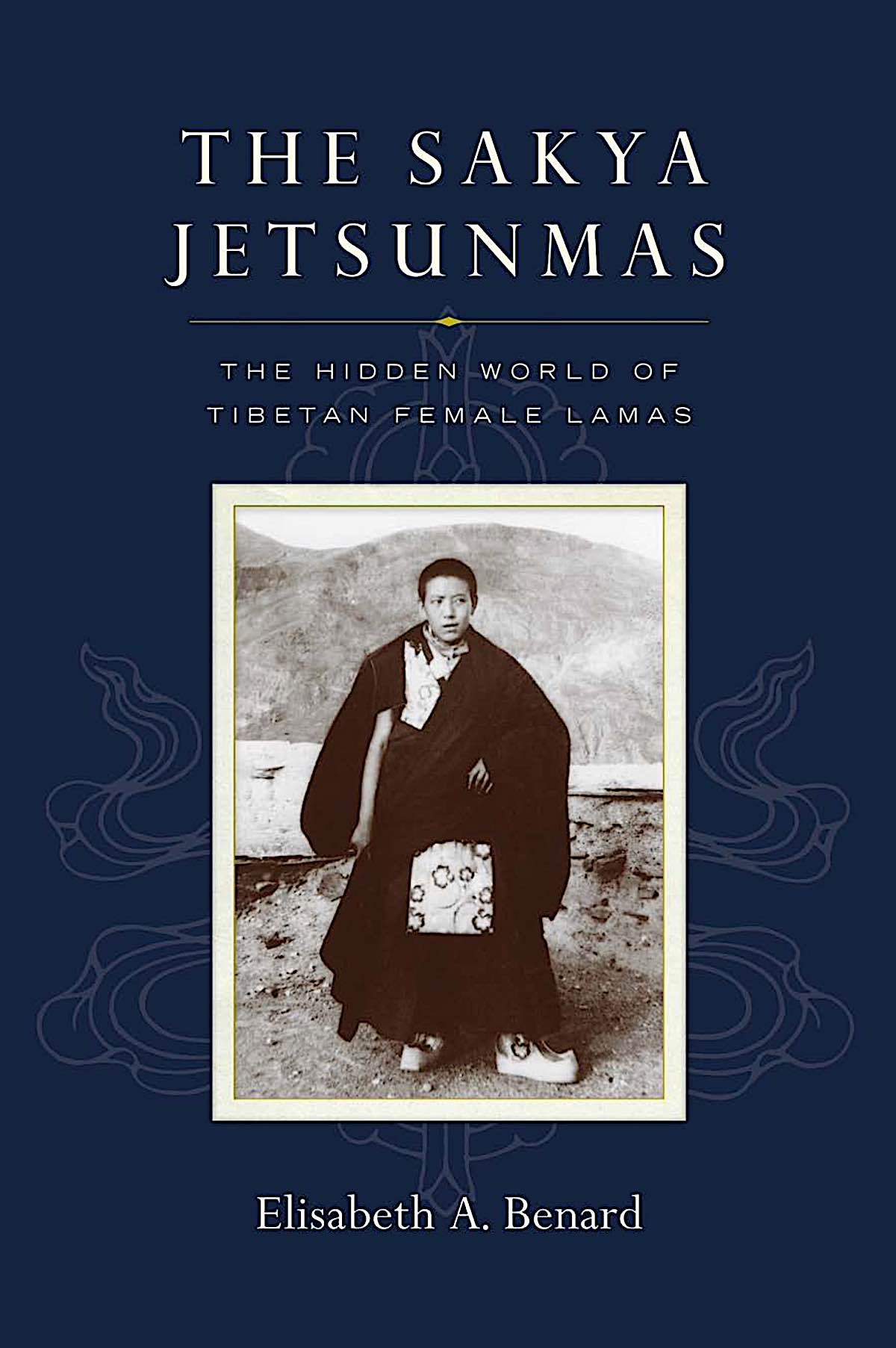

“Extraordinary” hardly seems an adequate label for the historical lives of the great Tibetan Buddhist Female Lamas of the Sakya lineage. These were highly realized teachers, known not only for wisdom, but for “activities” and “accomplishments.” Elisabeth Benard’s highly readable account of the female lamas of Tibet — The Sakya Jetsunmas: The Hidden World of Tibetan Female Lamas — brings these precious histories to life.

We requested permission to excerpt the chapter from the book “Lama to All: Jetsunma Tamdrin Wangmo (1836 – 96).”

- Available from your favorite bookseller, or Amazon (details below.)

Excerpt: Chapter four

Lama to All:

Jetsunma Tamdrin Wangmo (1836–96)

Another of the great jetsunmas in the Sakya tradition is the distinguished scholar, teacher, practitioner, and yogi Jetsunma Tamdrin Wangmo Kalzang Chokyi Nyima (1836–96). Her full name means the revered female master (jetsunma), an emanation of the horse-necked deity who is a wrathful manifestation of compassion (tamdrin), powerful woman (wangmo), good fortune (kalzang), the one who rejoices in the Buddhist teachings (chokyi), and the sun (nyima). Tibetans give auspicious names to their children because it is believed that one should begin with the positive in order to ensure a beneficial beginning and, hopefully, a wonderful life. In the case of Jetsunma Tamdrin Wangmo, each name foreshadowed an aspect of her extraordinary life.

Early Life

In many Tibetan Buddhist biographies of great teachers, one finds stories of unusual circumstances during the pregnancy, foretelling dreams, and easy delivery at birth. None of these is found in the biography of Jetsunma Tamdrin Wangmo written by her great-nephew the 39th Sakya Trizin Dragshul Trinlei Rinchen (1871–1935), who was also one of her main disciples and who regarded her as one of his root gurus. In fact, he records nothing of her early life except who her parents and early teachers were. Her father, Ngawang Kunga Rinchen (Ngag dbang kun dga’ rin chen, 1794–1856), had shared a wife with his older brother Pema Dudul Wangchuk (1792–1853), who reigned as the 33rd Sakya Trizin from 1806 to 1843. In his early adult life, however, Ngawang Kunga Rinchen decided to remarry and build a new home for this new family in Sakya. This home became known as the Phuntsok Palace. As in most Sakya Khon marriages, the family selected a young woman from a noble family—in this case, Nyima Dawa Wangmo (Nyi ma zla ma dbang mo) from the Samte (bSam lte) noble family. We know virtually nothing about her except that she had three daughters and two sons.

Of the five, Jetsunma Tamdrin Wangmo was the oldest. The second child was Jetsunma Kalzang Tenzin Wangmo (n.d.), and the fifth and youngest was Jetsunma Tsultrim Wangmo (n.d.). Nyima Dawa Wangmo’s first son was Ngawang Kunga Sonam (Ngag dbang kun dga’ bsod nams, 1842–82), who reigned as the 36th Sakya Trizin from 1866 to 1882, and her second son was Kyabgon Chokyi Langpo (Phyogs kyi glang po, 1844–66). This was Jetsunma Tamdrin Wangmo’s immediate family.

Her Early Teachers

In the Sakya Khon family, it is frequently a father or uncle who chooses the teacher for a child. In Jetsunma Tamdrin Wangmo’s case, her paternal uncle, Pema Dudul Wangchuk, appointed the Lopon Loter Zangpo (n.d.) as her main tutor. Lopon Loter Zangpo taught her how to read and chant prayers, laying an excellent foundation for her.

Like every member in the Sakya Khon family, she was given empowerments of important deities whom Tibetan Buddhists believe will help them throughout this life and future lives. In the Sakya tradition, these include Hevajra (Kye Dorje), Vajrayoginī (Naro Khachod), Vajrakīlaya (Dorje Phurba), and Sarvavid Vairocana (Kunrig Nampar Nangdze). Each of these deities has various empowerments according to different transmission lineages, and each has particular teachings and commentaries. She learned the history of the deity; the meditative practices, or sādhanas (mngon rtog); how to make appropriate mandalas (dkyil ’khor) to represent the residence of the deity in a precise mathematical manner and with decorations; the correct sacrificial offerings (gtor ma); daily offering chants (bskang gso); and dedication prayers. In addition, she learned all the traditional chants and accompanying music for each practice. This involved a tremendous amount of effort, years of sustained commitment, and a compelling desire to attain enlightenment for the sake of all beings (bodhicitta).

The Teachings

Jetsunma Tamdrin Wangmo had numerous teachers. Her biography relates how her father and his brother, her paternal uncle Pema Dudul Wangchuk, imparted many teachings to her. For instance, she received empowerments and explanations of how to practice and perform the rituals of Vajrakīlaya. Vajrakīlaya is a deity who is portrayed as a wrathful emanation so as to remove obstacles and eliminate forces that are inimical to fostering compassion and wisdom. The Khon family has been following this ancient practice of Vajrakīlaya since the eighth century, when the great Indian yogi Guru Padmasambhava came to Tibet; among his students who received this teaching was Khon Nagendra Raksita, a very early member of the Khon family. The Sakyas celebrated Vajrakīlaya every year throughout the entire seventh lunar month, and despite all the upheavals in 1959, when many Tibetans fled into exile, including the Khon family, these rituals were performed, clearly indicating the paramount importance of Vajrakīlaya in the Sakya tradition.

Jetsunma Tamdrin Wangmo also received the empowerment of the deity Cakrasaṃvara (Tib. ’Khor lo bde mchog) according to the lineage tradition of the Indian adept (siddha) Krishnapada. Cakrasaṃvara can be translated as “Wheel of Supreme Bliss”; supreme bliss is a sign that one has attained the realization of reality. Furthermore, Cakrasaṃvara is classified as one of the highest of tantric empowerments. Sometimes one must have received a major empowerment in the highest tantra classification in order to receive other initiations, so this paved the way for her to receive other major empowerments in the future.

In Tibetan Buddhism, many deities have different forms. Cakrasaṃvara has fifty different forms, and some of his forms are the father/mother or yab/yum one, depicting two deities in sexual union. The “father” aspect represents the method—namely, the compassion—needed to sustain a lifelong commitment to striving for the goal of helping all sentient beings. But, of course, compassion is not enough on its own. The “mother” aspect therefore represents wisdom. If one does not have the proper understanding, or wisdom, to know how to help a sentient being effectively, one can create more problems and confusion. It is essential to have both compassion and wisdom in order to help others.

Cakrasaṃvara is seen as a male deity, and his female counterpart is the great goddess known as Vajrayoginī or Vajravārāhī. Though she is his counterpart, for many practitioners Vajrayoginī is paramount, and in many depictions of Vajrayoginī she is represented as a sole goddess, without a visible partner.

This leads us to next empowerment and teachings Jetsunma Tamdrin Wangmo received: the extraordinary Vajrayoginī from the Indian mahāsiddha Nāropa lineage. As seen in Chapter 3, this lineage has been passed down from one generation to the next in the Sakya Khon family for almost a thousand years, and some of the great Sakya jetsunmas are considered to be an emanation of Vajrayoginī. Jetsunma Tamdrin Wangmo received this empowerment and its extensive teachings from her family. She conferred these teaching very often in her lifetime, according to her biography. This teaching and her transmission of it were one of her main legacies.

Now that she had received the foundational empowerments, Jetsunma was instructed by her older half brother, Dorje Rinchen, in the Sakya’s main practice of Lamdre, or the Path with the Result. She received both the exoteric, more public teaching and the esoteric or “uncommon” teaching. She practiced the teachings of both these levels throughout her life and became a recognized master of these teachings by giving them numerous times.

Knowledge concerning these deities and the teachings associated with them may be overwhelming for most people, but for a future teacher, it is imperative to receive as many empowerments and teachings as one is capable of understanding—and also to be able to practice them. Since people have a wide variety of inclinations, temperaments, abilities, and interests, a skillful teacher must have the means to tailor the teachings to each individual student. This does not mean that the teachings are changed, but rather that the teacher’s knowledge is vast, so that she or he is well equipped to select the appropriate approach for each disciple. Thus, in Tibetan Buddhism, one encounters a pantheon of deities, both extensive and varied. The forms they assume are numerous: some appear to be very wrathful, for those beings who need to be subdued; others are extremely peaceful, for those who need kindness and love; others are in the father/mother union, to emphasize the importance of the union of compassion and wisdom in attaining enlightenment; and still others are semi-wrathful form, for those who need a jolt to keep them on the spiritual path.

In Tibetan Buddhism, one finds compendiums of meditational deities that can include a hundred deities or more. A popular one among the Sakyas is One Hundred Methods of Accomplishment (Grub thabs rgya rtsa). Jetsunma received these empowerments from her older half brother Dorje Rinchen. He also gave her the blessings and transmissions of two other important deities, Yamāntaka (Destroyer of Death) and Mahākāla (Great Black One).

Retreats and Religious Commitments

One of the obligatory practices for those who undergo these initiations is a solitary retreat for each of the deities from whom one has received a major empowerment. One of the most extensive retreats is the one dedicated to Hevajra, which lasts from seven to eight months. Most others are shorter but still of significant duration, such as the Vajrayoginī retreat, which lasts from three to four months. Some are only a month long, or less. Jetsunma Tamdrin Wangmo did retreats on Hevajra, Vajrayoginī, Vajrakīlaya, Pañjaranātha Mahākāla, the powerful subjugator-goddess Kurukulle, and Vajrapāṇi Bhutaḍāmara. These many retreats require a considerable amount of time. Only a great practitioner would be able to accomplish so much. Furthermore, she kept her daily commitments, which are known as the Four Unbreakable Practices (Chak mey nam zhi): the practices of Hevajra (Lam dus), the profound path of Guru Yoga (Lam zap), Virūpa protection meditation (Bir sung), and Vajrayoginī (Naljorma). On the eighth, fourteenth, twenty-third, and twenty-ninth day of each lunar month, she made offerings to the beings that protect the Dharma, the Buddhist teachings.

Also, it was standard that all blood members of the Sakya Khon family take the three religious vows—prātimokṣa, bodhisattva, and tantra. The first vow, prātimokṣa, is the promise to avoid all nonvirtuous actions that impede individual liberation from cyclic existence. Jetsunma Tamdrin Wangmo received the three vows from the abbot Tashi Chopel of the Great Temple in Sakya. She is remembered as one who kept her vows vigilantly and continuously.

Other Buddhist Activities

In addition to receiving initiations and teachings of various deities and taking vows to follow spiritual practices, Jetsunma Tamdrin Wangmo read spiritual texts. For instance, she managed to read the Kangyur two times completely. For Tibetans, the Kangyur is the sacred canon comprising the “translated words” of the Historical Buddha. Different versions of this sacred canon exist, consisting of between 101 to 120 volumes, with a total of over 70,000 pages. In addition, she read the genealogies of Sakya Khon families, the spiritual biographies of great Sakya masters, and many other biographies of spiritual adepts. When she read these, she often cried. In his biography of Jetsunma Tamdrin Wangmo, her great-nephew the 39th Sakya Trizin Dragshul Trinlei Rinchen notes that her tears showed that she had a strong faith and the heart of bodhicitta. In Buddhism, anyone who aspires to help others needs to develop bodhicitta—the compassionate wish to attain enlightenment for the benefit of all beings.

Dragshul Trinlei Rinchen comments further, noting that whoever reads these books and has this kind of feeling is rare, for most people do not have this feeling. Moreover, he writes, “these days” lamas make false claims. They pretend to have clairvoyance, so as to understand past and future lives, but they have none of these powers. Jetsunma Tamdrin Wangmo was the opposite. She never claimed to have such powers. Yet when she practiced the art of divination by using dice, her interpretation of the outcome was accurate and correct.

There is a long tradition of divination in Tibetan Buddhism. A diviner or lama may use dice, a rosary, or a bronze mirror to assess a particular situation and to look into someone’s future. There are even people who have the ability to go into a trance and become mediums for oracles. Most lamas carry with them a small circular metal or wooden box that holds dice because their devotees regularly request a divination when they see their lama. After receiving a request, the lama prays to a particular deity, then rolls the dice in the box and interprets the result for the devotee.

Many lamas are trained at an early age to interpret the reading of the dice. Different lamas rely on different deities, depending on their connection to a particular deity. One popular deity is the Bodhisattva of Wisdom, Mañjuśrī. Each die has six sides, and each side corresponds to one of the letters in the mantra of Mañjuśrī. Before throwing the two dice, the lama must visualize Mañjuśrī and feel that Mañjuśrī is revealing the outcome through the dice. Once the dice are thrown, the lama needs to interpret each letter. This can take years of experience. Some lamas are considered much better than others in pronouncing the correct result. Clearly, Jetsunma Tamdrin Wangmo was esteemed as a lama who gave accurate outcomes.

Author Bio: ELISABETH BENARD (Ph.D. Columbia University) is a professor emerita of religion at the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington. She is the author of Chinnamastā: The Aweful Buddhist and Hindu Tantric Goddess (Motilal Banarsidass, 1994) and numerous scholarly articles. She is a longtime student of H.H. the Forty-First Sakya Trizin (now Trichen) and H.E. Jetsun Kushok.

About the Book

- Title : The Sakya Jetsunmas: The Hidden World of Tibetan Female Lamas

- Publisher : Snow Lion (March 1, 2022)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 320 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1645470911

- ISBN-13 : 978-1645470915

- Available in paperback and kindle

- On Amazon>> (this is an affiliate link), or at your favorite book seller.

- On Shambala’s site>>

More articles by this author

Offering Light for Saga Dawa Duchen and the Month of Merits: Buddha’s Birthday, Enlightenment and Paranirvana 100 Million Merit Day

Who is my Enlightened Life Protector Based on Tibetan Animal Sign Zodiac in Buddhism? According to Mewa, Mahayana tradition and Kalachakra-based astrology (with Mantra Videos!)

Bodhisattva Vow and the Bonding Aspiration of the 5 Buddha Families: Reversing Dharma Downfalls, Purifying Karma, and Restoring Commitments

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Lee Kane

Author | Buddha Weekly

Lee Kane is the editor of Buddha Weekly, since 2007. His main focuses as a writer are mindfulness techniques, meditation, Dharma and Sutra commentaries, Buddhist practices, international perspectives and traditions, Vajrayana, Mahayana, Zen. He also covers various events.

Lee also contributes as a writer to various other online magazines and blogs.