Kucchivikara-vattha: The Monk with Dysentery (Sutra teachings) “If you don’t tend to one another, who then will tend to you?”

A Buddha Weekly reader requested we highlight the teaching of “The Monk with Dysentery”.

“I read somewhere that once Buddha came back to his monastery after a usual walk and found one of the monks was suffering while none of the other monks who were meditating came to help this suffering monk. Buddha chastised the meditating monks for not helping their suffering brother monk. I would like to know the complete story and a reference to it. Thanks.”

The famous story of The Monk with Dysentery is found in Mv 8.26.1-98, the Kucchivikara-vatthu. [Full Kacchuvikara-vatthu: The Monk with Dysentery in English below.]

In this wonderful story — one of the earliest compassionate teachings on “treat others as you would have others treat you” — Shakyamuni Buddha came across a sick monk “fouled in his own urine and excrement,” with no one attending to him. As Buddha questions the other monks he discovers that no one is helping the monk because the monk had never helped them in return, leading to his famous teaching:

“If you don’t tend to one another, who then will tend to you? Whoever would tend to me, should tend to the sick.”

The Buddha’s words are very reminiscent of Jesus Christ’s words in the Book of Matthew:

“Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me.”

Although Buddha spoke these words hundreds of years before Jesus, these words are a core truth of all great religions — compassion.

[Full text below.]

Kucchivikara-vatthu: The Monk with Dysentery

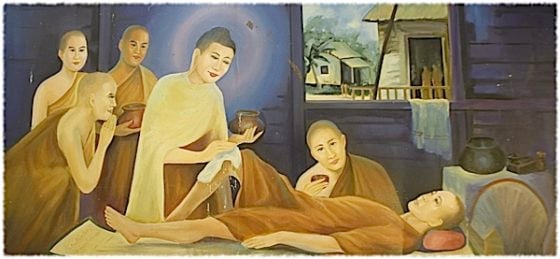

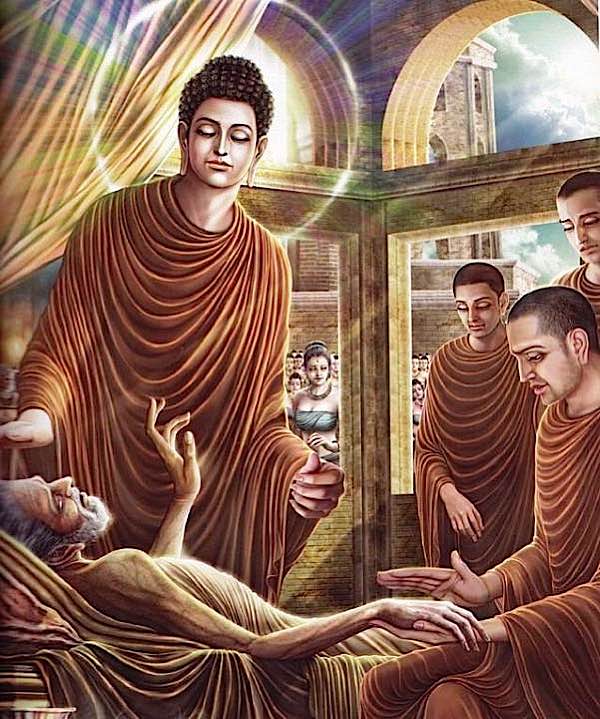

Now at that time a certain monk was sick with dysentery. He lay fouled in his own urine & excrement. Then the Blessed One, on an inspection tour of the lodgings with Ven. Anandaas his attendant, went to that monk’s dwelling and, on arrival, saw the monk lying fouled in his own urine & excrement. On seeing him, he went to the monk and said, “What is your sickness, monk?”

“I have dysentery, O Blessed One.”

“But do you have an attendant?”

“No, O Blessed One.”

“Then why don’t the monks attend to you?”

“I don’t do anything for the monks, lord, which is why they don’t attend to me.”

Then the Blessed One addressed Ven. Ananda: “Go fetch some water, Ananda. We will wash this monk.”

“As you say, lord,” Ven. Ananda replied, and he fetched some water. The Blessed One sprinkled water on the monk, and Ven. Ananda washed him off. Then — with the Blessed One taking the monk by the head, and Ven. Ananda taking him by the feet — they lifted him up and placed him on a bed.

Then the Blessed One, from this cause, because of this event, had the monks assembled and asked them: “Is there a sick monk in that dwelling over there?”

“Yes, O Blessed One, there is.”

“And what is his sickness?”

“He has dysentery, O Blessed One.”

“But does he have an attendant?”

“No, O Blessed One.”

“Then why don’t the monks attend to him?”

“He doesn’t do anything for the monks, lord, which is why they don’t attend to him.”

“Monks, you have no mother, you have no father, who might tend to you. If you don’t tend to one another, who then will tend to you? Whoever would tend to me, should tend to the sick.

“If one’s preceptor is present, the preceptor should tend to one as long as life lasts, and should stay until one’s recovery. If one’s teacher is present, the teacher should tend to one as long as life lasts, and should stay until one’s recovery. If one’s student is present, the student should tend to one as long as life lasts, and should stay until one’s recovery. If one’s apprentice is present, the apprentice should tend to one as long as life lasts, and should stay until one’s recovery. If one who is a fellow student of one’s preceptor is present, the fellow student of one’s preceptor should tend to one as long as life lasts, and should stay until one’s recovery. If one who is a fellow apprentice of one’s teacher is present, the fellow apprentice of one’s teacher should tend to one as long as life lasts, and should stay until one’s recovery. If no preceptor, teacher, student, apprentice, fellow student of one’s preceptor, or fellow apprentice of one’s teacher is present, the sangha should tend to one. If it does not, [all the monks in that community] incur an offense of wrong-doing.

“A sick person endowed with five qualities is hard to tend to: he does what is not amenable to his cure; he does not know the proper amount in things amenable to his cure; he does not take his medicine; he does not tell his symptoms, as they actually are present, to the nurse desiring his welfare, saying that they are worse when they are worse, improving when they are improving, or remaining the same when they are remaining the same; and he is not the type who can endure bodily feelings that are painful, fierce, sharp, wracking, repellent, disagreeable, life-threatening. A sick person endowed with these five qualities is hard to tend to.

“A sick person endowed with five qualities is easy to tend to: he does what is amenable to his cure; he knows the proper amount in things amenable to his cure; he takes his medicine; he tells his symptoms, as they actually are present, to the nurse desiring his welfare, saying that they are worse when they are worse, improving when they are improving, or remaining the same when they are remaining the same; and he is the type who can endure bodily feelings that are painful, fierce, sharp, wracking, repellent, disagreeable, life-threatening. A sick person endowed with these five qualities is easy to tend to.

“A nurse endowed with five qualities is not fit to tend to the sick: He is not competent at mixing medicine; he does not know what is amenable or unamenable to the patient’s cure, bringing to the patient things that are unamenable and taking away things that are amenable; he is motivated by material gain, not by thoughts of good will; he gets disgusted at cleaning up excrement, urine, saliva, or vomit; and he is not competent at instructing, urging, rousing, & encouraging the sick person at the proper occasions with a talk on Dhamma. A nurse endowed with these five qualities is not fit to tend to the sick.

“A nurse endowed with five qualities is fit to tend to the sick: He is competent at mixing medicine; he knows what is amenable or unamenable to the patient’s cure, taking away things that are unamenable and bringing things that are amenable; he is motivated by thoughts of good will, not by material gain; he does not get disgusted at cleaning up excrement, urine, saliva, or vomit; and he is competent at instructing, urging, rousing, & encouraging the sick person at the proper occasions with a talk on Dhamma. A nurse endowed with these five qualities is fit to tend to the sick.”

More articles by this author

Profound simplicity of “Amituofo”: why Nianfo or Nembutsu is a deep, complete practice with innumerable benefits and cannot be dismissed as faith-based: w. full Amitabha Sutra

“Torches That Help Light My Path”: Thich Nhat Hanh’s Translation of the Sutra on the Eight Realizations of the Great Beings

Maha Mangala Sutta, Life’s Highest Blessings, The Sutra on Happiness, the Tathagata’s Teaching to Gods and Men

Miracles of Buddha: With the approach of Buddha’s 15 Days of Miracles, we celebrate 15 separate miracles of Buddha, starting with Ratana Sutta: Buddha purifies pestilence.

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Josephine Nolan

Author | Buddha Weekly

Josephine Nolan is an editor and contributing feature writer for several online publications, including EDI Weekly and Buddha Weekly.