Bodhidharma, One-Shoed sage: The Towering and Profound Life and Teachings of the Legendary Zen Master and Martial Artist

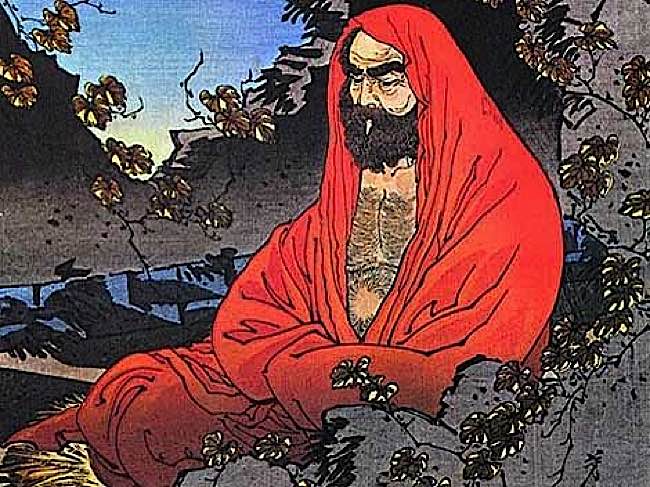

Aside from Gautama Buddha himself, no one rose to the level of epic, towering fame and Buddhist history greater than the one-shoed sage of Shaolin fame, Bodhidharma. Like Buddha, his life is both historical and legendary. Like Buddha, he was a prince who renounced the worldly.

Bodhidharma not only brought Chan Buddhism to China, but he is also credited with Shaolin martial arts and a profound lineage of extraordinary teachings.

A Teacher with One Shoe and Very Few Words?

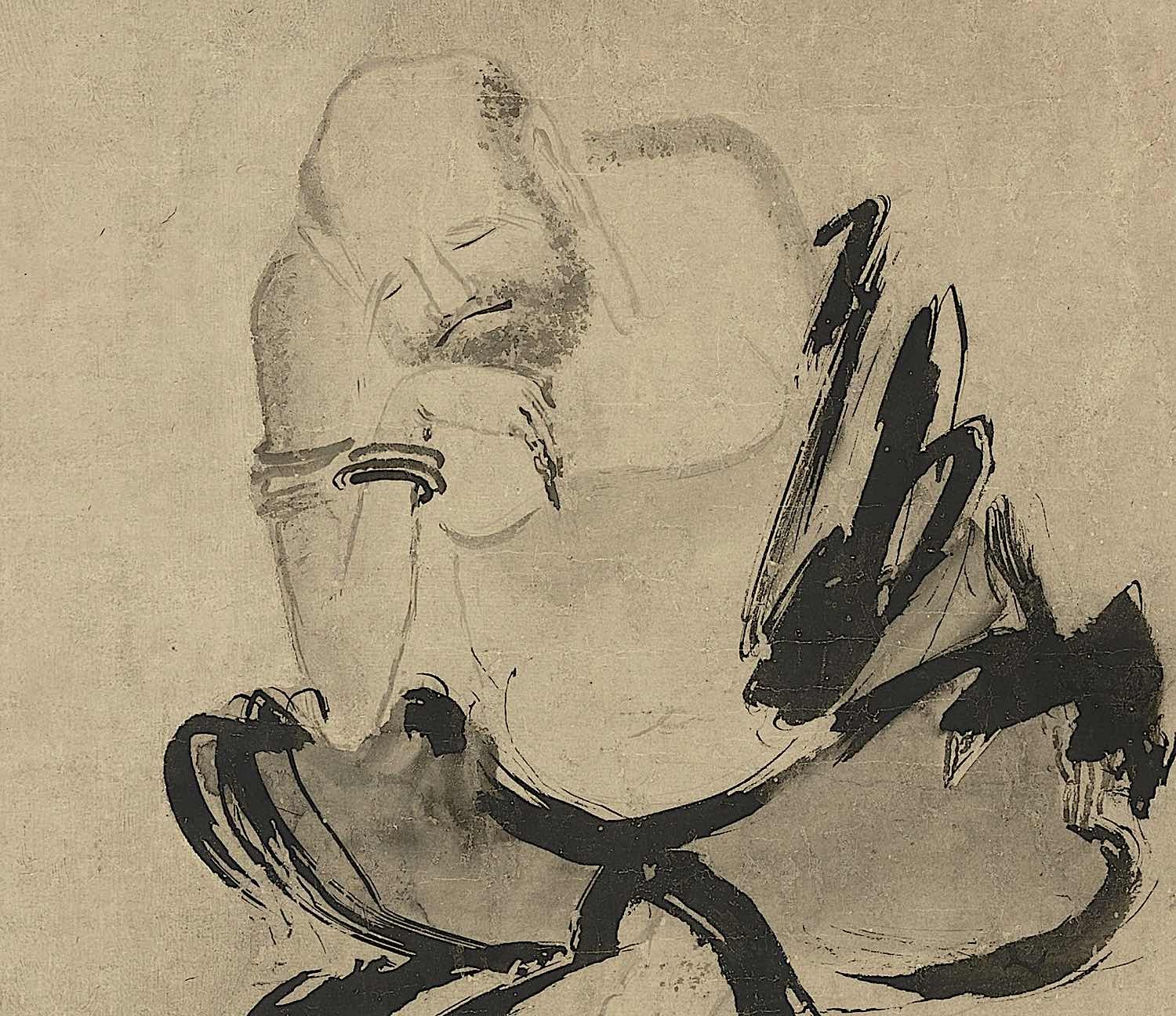

The stories of his life sound both mystical and deceptively bland at the same time, like the legend of his one-shoed hike over the mountain pass, or the years of his life he spent staring at the cave wall. He became a famous teacher by using very few words. The few words he spoke were often riddles or rebukes. He’s famous for cutting off his eyebrows to ensure he stayed awake when meditating. He taught stillness but inspired the rise of strenuous Shaolin martial arts. He reprimanded emperors for seeking fame, yet he, himself became one of the most famous people of his time. He would have thrown his other shoe at you if you told him he was famous.

The End of the Story is the Beginning

You’re curious about the shoe, right? We might as well start this story at the end in that case. This is the ending of the story, but also the beginning. You’ve probably seen images of Bodhidharma hiking up a mountain pass with a pole on his shoulder, walking barefoot, his only remaining shoe hanging from the pole.

What made this incident famous was not that the great Sage was barefoot. It was all about the timing.

At that time, the Chinese diplomat, Songyun was headed back to court, through a pass in the Pamir Mountains. On his way, he saw the Great Sage, who by now as famous in the area, climbing the pass, alone. What struck Songyun as odd, was that the sage walked barefoot on sharp rocks. His one shoe was hanging from a pole on his shoulder.

Respectfully he asked the sage where he was going. The answer suprised Songyun. The Sage said, “I am going home.”

This puzzled the diplomat, since Bodhidharma had been in the area for as long as he could remember. When he tried to ask, Bodhidharma just abruptly told Songyun that the reason would become clear once Songyun arrived in Shaolin. Before he left, he instructed Songyun to keep the encounter a secret.

Of course, Diplomats aren’t known for keeping their mouths closed. As soon as he returned to the court, Songyun told the Emperor proudly, that he had encountered the great sage. The Emperor was enraged, and had the poor diplomat arrested for lying to court. Poor Songyun found out, as he was hauled away, that Bodhidharma died one week earlier.

Screaming and shouting his innocence, Songyun stood firm on his claims and the Emperor finally ordered the tomb to be opened, even though countless witnesses saw the Sage buried.

Typical of Bodhidharma’s mysterious life, they found his tomb empty. The only contents were a single shoe. The other shoe was hiking across the mountains on the way to home.

Even Bodhidharma’s death became a riddle. The entire nation was transfixed by the astonishing story of Bodhidharma’s after-death pilgrimage.

This was typical of Bodhidharma’s life. His every teaching was a challenge, a provocation, or a shocker.

Related Features on Buddha Weekly:

- Bodhidharma the Epic Journey to China

- Bodhidharma’s breakthrough teaching: Shastra on Eradicating Appearances>>

- Bodhidharma – Who Stands Before Me?

- Our Full Chan and Zen Feature Section with Many Feature Stories>>

Back to the Beginning: Confronting Emperor Wu

We wind the way-back clock to years earlier, when Bodhidharma first met the emperor. He had just left his home after his teacher Prajna Tara passed away. He decided to carry the teachings to China, and undertook the arduous journey on foot. When he finally arrived, Emperor Wu, who was a devout Buddhist, summoned Bodhidharma for an audience, excited by the prospect of learning from a great teacher.

Emperor Wu began their audience by having his subjects recite his long list of meritorious and charitable acts. Bodhidharma stared at the wall, unblinking, as the steward recounted all the money the Emperor spent on monasteries. They droned on endlessly about the Emperor’s efforts to translate Buddhists scriptures and texts, and his gracious permission for his subjects to ordain as monks and nuns.

At the end of this virtual inventory, the Emperor asked Bodhidharma:

“What merit have I accumulated by all this wholesome action?”

He must have felt secure in his positive karma. No matter what evil deeds he might have committed in his life, inevitable for kings and emperors, his vast treasure chest of donations must have paved the way to Nirvana?

To the Emperors shock, Bodhidharma replied: “None whatsoever!”

To say he was spitting mad might have understated it. The Emperor must have glared at the serene pilgrim, a dirty man in rags, covered in dust from hundreds of miles of travel. We can imagine the Emperor’s fists clenching and unclenching, sputtering, glaring.

Bodhidharma’s Quiet Fame

Long after he tossed the ungrateful Sage out of his court, instructing Bodhidharma never to return, his advisors finally calmed him down and explained that there is no “merit” to good deeds when you’re motivated by your own self-interest. The king’s greed for fame, acclaim and good karma had not only erased any possible thought of merit, it had actually created negative karma.

Poor Emperor Wu. Through his reign, Bodhidharma’s fame would haunt him. Many times he asked Bodhidharma to return for another audience, but Bodhidharma never responded. Even after Bodhidharma passed away, the one-shoed sage appeared to mock the Emperor “on his way home.”

Bodhidharma Wall

Both his arrival, and exit were shocking. And, both were teachings, with virtually no words spoken. This exemplified Bodhidharma’s life and teachings. He had little to say — yet what he said spoke profound volumes.

He taught Buddha Dharma, but did not teach from scriptures or sutras. He taught compassion but was famous for his temper, as depicted in his scowling face in paintings and statues.

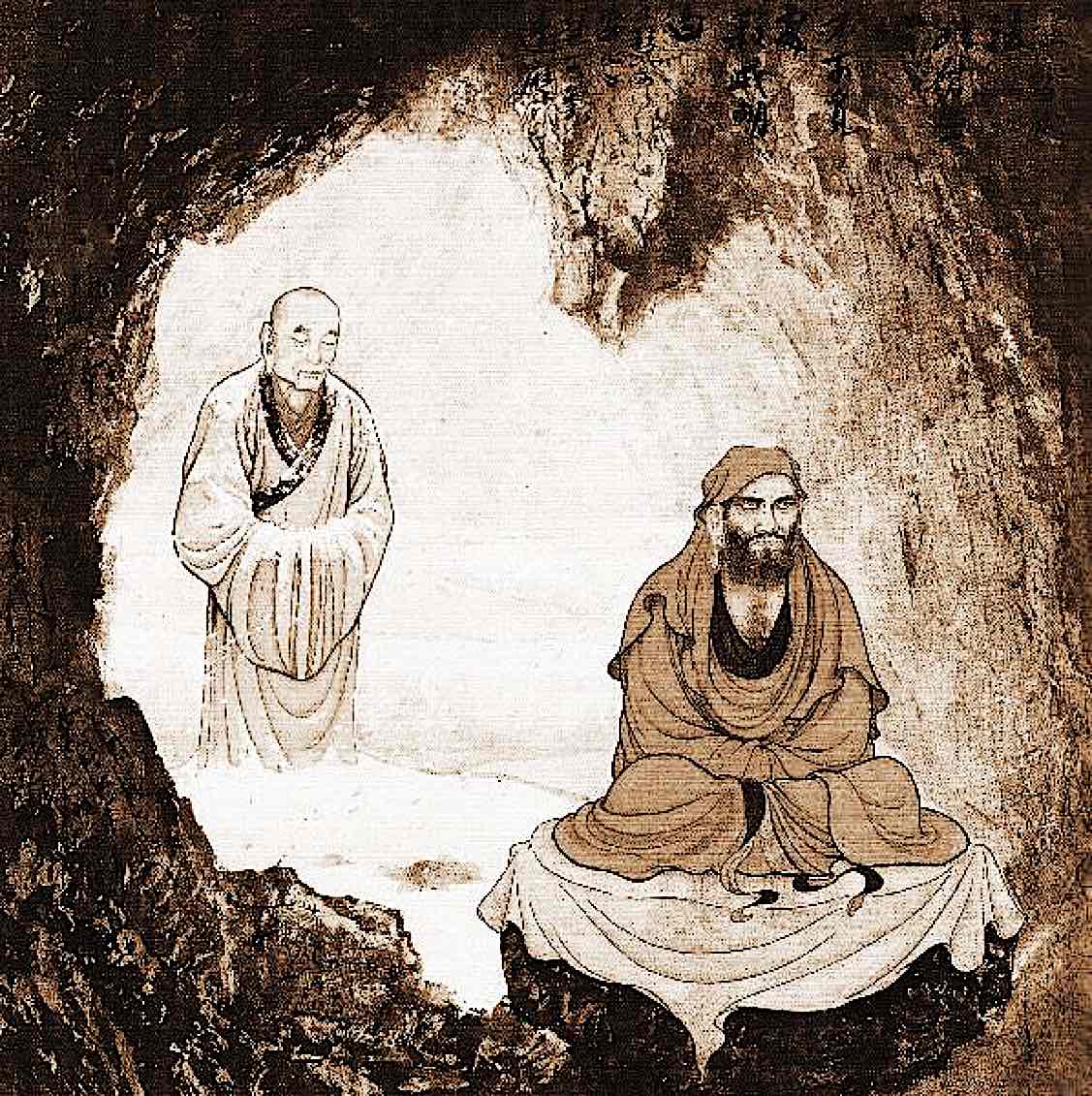

We began and ended the story with two events involving the Emperor. Between those two events, Bodhidhama’s fame grew yet again through the simple act of meditating for years in front of a wall, unmoving. Monks continually asked him for teachings, but he ignored them all, and simply stared at the wall.

He was teaching them, by this heroic demonstration of “wall gazing”. Later, this became known as Bodhidharma Wall. Today monks meditate in front of blank walls.

Dàzǔ Huìkě 大祖慧可 Pacifying the Heart

Even those years of silence in the cave were marked by shocking teaching events. Most famous of these was the desperate monk 大祖慧可, who was unable to find peace even in the Shaolin Monastery.

He begged day after day for teachings, ignored by the great sage. You might have wondered what the colloquial saying “I’d give up my right arm” means. We have Dàzǔ Huìkě 大祖慧可 to thank.

After the poor monk stood outside, buried to the waist in falling snow, Bodhidharma finally spoke to him.

“The old masters broke their bones and ground the very marrow of them for the Dharma; yet you with your half-hearted efforts come to demand it!”

In response, Dàzǔ Huìkě 大祖慧可 , without hesitation, cut off his own arm at the elbow. He did not even scream. The blood flowed, but he stood there, waiting for Bodhidharma’s response. Finally, the sage said:

“What have you come for?”

Dàzǔ Huìkě 大祖慧可, ignoring his limb on the ground, said, “My heart is not at peace. Please pacify my heart.”

After a moment, the sage said:

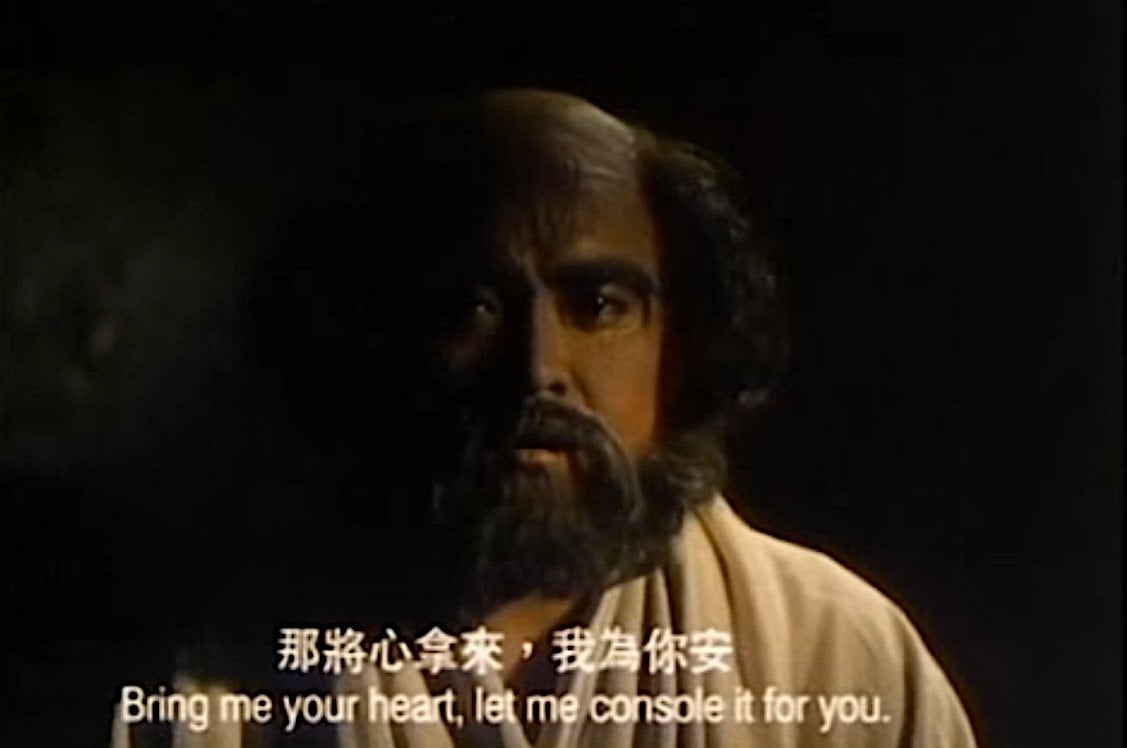

“Bring me your heart and I will pacify it.”

Dàzǔ Huìkě 大祖慧可 went away for a long while, and thought about the encounter. Finally, he returned to the Sage and said:

“I cannot find my heart.”

Bodhidharma answered, “There, I have pacified it.”

Passing the Bowl

Dàzǔ Huìkě 大祖慧可 was to become Bodhidharma’s most famous student, and in time, as tradition has it, Bodhidharma passed his bowl and robes on to his one-handed disciple. Dàzǔ Huìkě 大祖慧可 became the second Patriarch of Chan Zen Buddhism. He is also the origin of the one-handed prostration of Shaolin monks.

Bodhidharma’s extraordinary teaching methods continued through his life. He taught the monks martial arts, and is credited with founding Shaolin kung fu to keep the monks and nuns fit and healthy. He also considered it a form of meditation. Mindfulness in all things, from eating, to martial arts, to sitting were the primary practices.

Even though Bodhidharma’s life story was full of encounters and exploits, his teachings can be summarized by his own four lines of profound wisdom — which can take a lifetime to unpack. He is credited with this famous four-line teaching that steers Chan and Zen practice even today. He wrote these four lines:

A special transmission outside the scriptures,

Not depending on words and letters;

Directly pointing to the mind,

Seeing into one’s true nature and attaining Buddhahood.

A Life of Riddles and Pointing

His life’s teaching method was to confound, confuse, and riddle. He came to embody practical Buddhism, taught through “pointing to the mind” with riddles, puzzling behavior, apparent rudeness, and silence. Why? So that we could see into our own true nature, and ultimately attain Buddhahood.

This is concisely taught in his most famous teaching, the Two Entrances and the Four Principles where he said:

Many roads lead to the Path, but basically, there are only two: Principle and Practice.

To enter by Principle means to realize the essence through instruction and to see that all living things share the same true nature, which isn’t apparent because it’s shrouded by sensation and delusion.

Those who turn from delusion back to reality, who meditate on walls, the absence of self and other, the oneness of mortal and sage, and who remain unmoved, even by scriptures, are in complete and unspoken agreement with the Principle.

Bodhidharma: Provocative and Profound

Bodhidharma was ultimately among the most grounded and practical of teachers in history, yet his life is filled with legend and mystery. He continued to confound and provoke mystery long after his death. We can picture him, walking barefoot over the mountain pass, “returning home” with his one shoe slung on the pole.

Without saying a word, we know he is telling us that he has, as with Dàzǔ Huìkě 大祖慧可, pacified our hearts.

More articles by this author

Offering Light for Saga Dawa Duchen and the Month of Merits: Buddha’s Birthday, Enlightenment and Paranirvana 100 Million Merit Day

Who is my Enlightened Life Protector Based on Tibetan Animal Sign Zodiac in Buddhism? According to Mewa, Mahayana tradition and Kalachakra-based astrology (with Mantra Videos!)

Bodhisattva Vow and the Bonding Aspiration of the 5 Buddha Families: Reversing Dharma Downfalls, Purifying Karma, and Restoring Commitments

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Lee Kane

Author | Buddha Weekly

Lee Kane is the editor of Buddha Weekly, since 2007. His main focuses as a writer are mindfulness techniques, meditation, Dharma and Sutra commentaries, Buddhist practices, international perspectives and traditions, Vajrayana, Mahayana, Zen. He also covers various events.

Lee also contributes as a writer to various other online magazines and blogs.