The Science Of Your Center: The Vagus Nerve, Your Meditation Highway, And The Parasympathetic Nervous System; How Meditation Works Positively on the Body

By Anne Green

Buddhism is known for its emphasis on meditation and meditative techniques. People from all walks of life have used Buddhist techniques to ‘relax’ and ‘de-stress’, despite neither being practising Buddhists nor indeed understanding much (if anything) about Buddhism itself. Without a doubt, meditation and the meditative techniques developed by Buddhists have helped a great many to cope with anxiety and mental health issues [1] — without necessarily understanding their deeper significance.

Scientists and doctors now take meditation seriously, no longer dismissing it as incompatible with medical science. Advances in the field of psychiatry, and a greater willingness to properly investigate mental health issues has brought scientific respect for the healing potential of meditation. As is typical of the scientific mindset, many have been determined to ‘get to the bottom’ of what causes the undeniably positive effects of meditation. They’ve discovered a lot — but one of the most interesting (and lesser known) findings concerns the action of meditative techniques upon the vagus nerve.

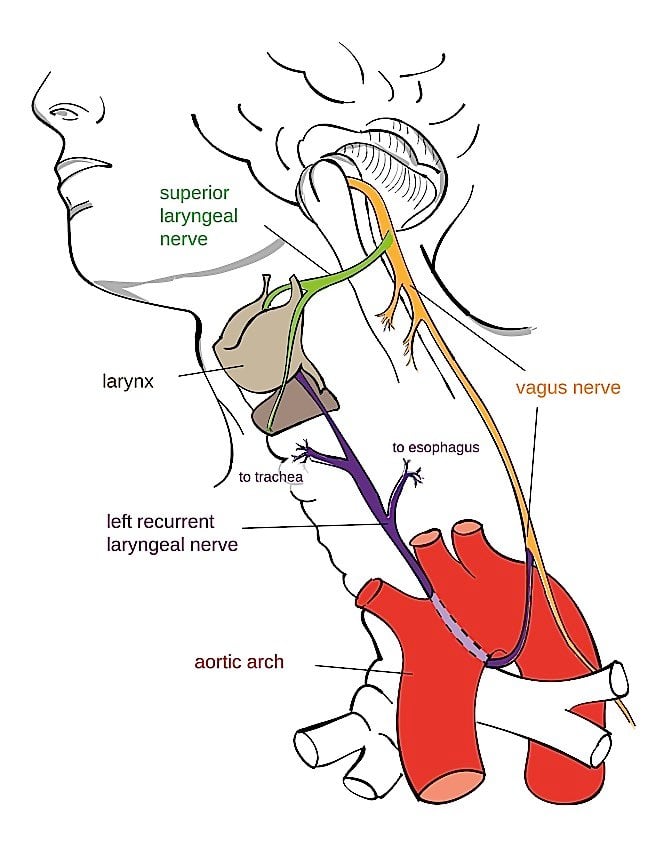

The Vagus Nerve — the Meditation Highway?

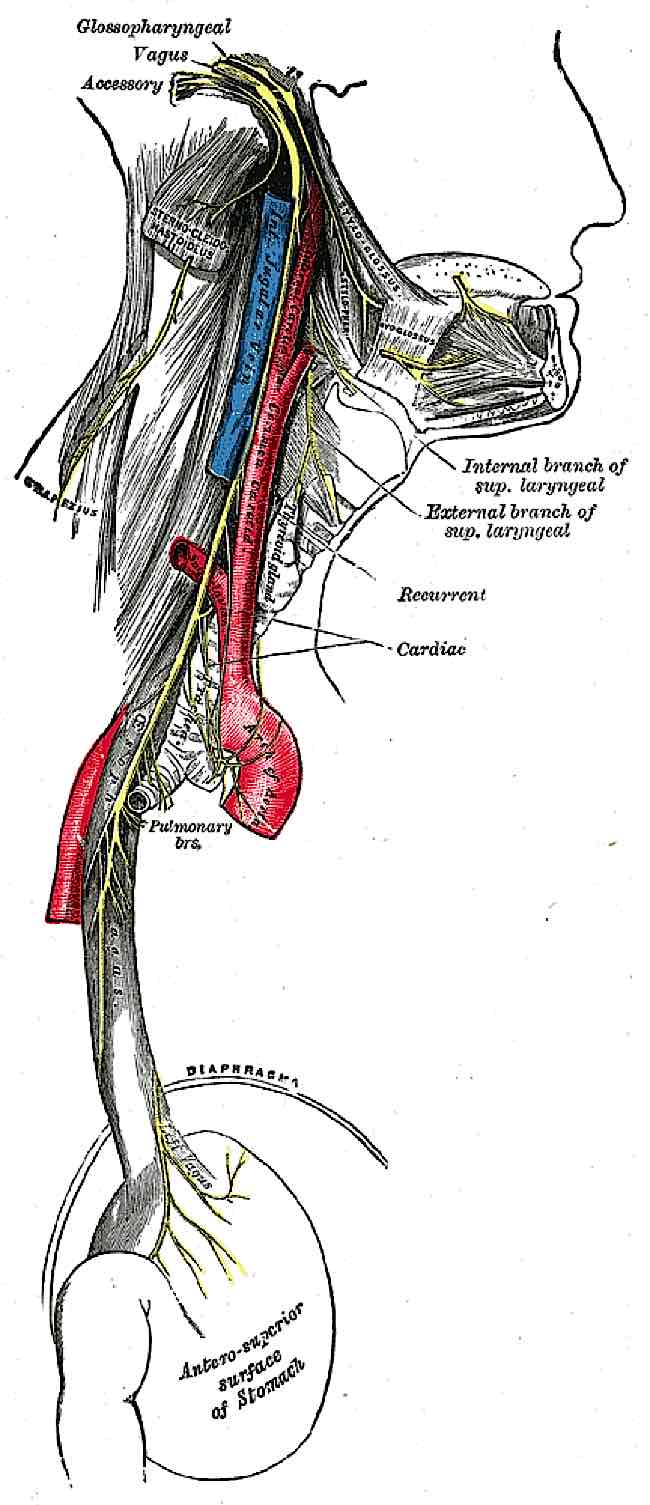

What’s the vagus nerve? Put simply, it’s one of the longest nerves in your body (sciatic nerve is the longest). The name roughly translates as ‘wandering nerve’, and it is apt. The vagus nerve travels from your brainstem, winding down throughout your body, to finish in your abdomen. On the way, it connects with many major organs, including heart and lungs. We’ve been aware of it for a very long time, and been similarly aware of the fact that the vagus nerve is semi-responsible for your body’s regulation of heart rate, breathing rate, digestion, and so forth.

It was previously assumed that the vagus nerve acted more or less on its own initiative ‑- that is, without the conscious input of the individual. While it could certainly be influenced by external factors such as stress, diet, or motion, it acted internally, and could not be consciously influenced. However, research revealed the deeply interconnected way in which consciousness and physicality can influence one another — and the vagus nerve. Described by some as a ‘hack’ [2] to the nervous system, the vagus nerve appears to be science’s answer to the vexed question of just how, precisely, Buddhist practices do what they do. And this kind of scientific verification and understanding has come just in time; more and more of us, it seems, are in need of the benefits of ‘vagal nerve stimulation’.

Modern Mental Dysfunction — and ‘Disconnected’ People

It’s a sad fact that mental health problems associated with stress and anxiety are enormously on the rise. Some experts believe we are generally more aware of mental health problems than we used to be, and that we’re also more likely to seek help for medical issues in general. This may well have contributed to the statistical rise in mental health issues. However, the sheer scale of the problem appears to indicate that we’re not just experiencing an increase in awareness, but a tangible increase in problems as well [3].

Reasons given for this vary. Political and economic instability has been blamed, as has social media and increased work pressures. On a more spiritual level, modern (and Western in particular) society has been accused of creating ‘disconnected’ people, struggling to find a sense of identity, a sense of self, and basic spiritual fulfillment in a rapidly changing world. Whatever the reason, we’re undoubtedly suffering from a surfeit of anxiety — which can be very dangerous.

Stress and anxiety can cause any number of mental health issues, which can in turn lead to physical health issues (substance abuse springs immediately to mind). We’ve known for some time that meditation (or ‘mindfulness’ — the secular, scientific, and increasingly popular meditative practice) can help with many of these problems [4].

As meditation becomes more popular, more and more people want to dissect the mysteries of meditation, and get to the bottom of what makes it so effective. After all, no scientific doctor would prescribe a therapy — however effective it’s been proven to be — without understanding it in full, analytical detail. This is where the vagus nerve comes in.

The Sympathetic And Parasympathetic Nervous System

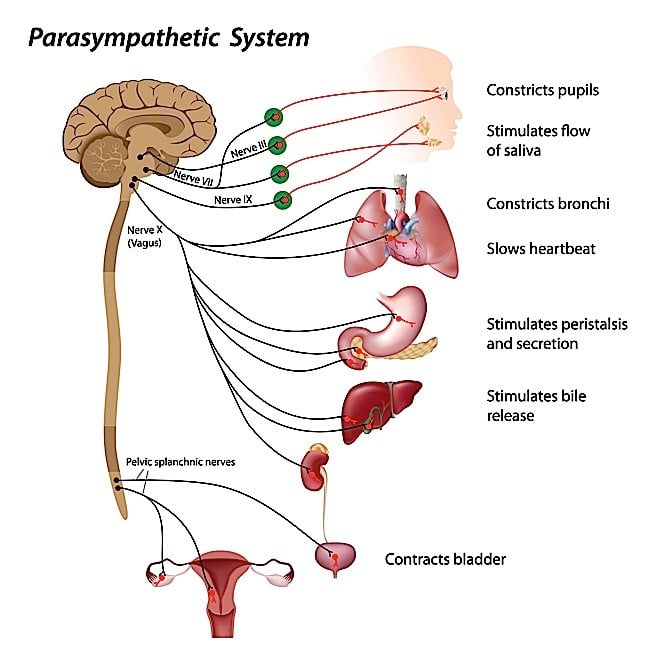

Our nervous systems are complex, wonderful things. They’re made up of many parts. One of these is the ‘sympathetic nervous system’ — responsible for the ‘Fight or Flight’ reaction. We’re all very familiar with the sympathetic nervous system and what it does. Your sympathetic nervous system is one branch of the ‘autonomic nervous system’ [5] — so called because it’s believed to act ‘autonomously’ (i.e. unconsciously). The other main branch of the autonomic nervous system is the ‘parasympathetic nervous system’ — about which we are in general considerably less informed.

The parasympathetic nervous system is responsible for the so-called ‘Rest and Digest’ functions, and we don’t pay as much attention to it as we should. To cut a long story short, when we meditate, we encourage our body to switch operational control from the ‘Fight or Flight’ system to the ‘Rest and Digest’ system. But how do we do this? And why is it important?

External Nervous Stimulation

We all know vaguely how the ‘Fight or Flight’ reaction works — we’re scared by something, and our sympathetic nervous system leaps into action to give us the ‘boost’ we need in order to either fight or flee our way out of danger. Specifically, this involves diverting resources from the deeper organs to your muscles, and from higher cognitive function to the ‘reptilian’ portion of your brain which deals with immediate survival. Adrenaline and cortisol are released to facilitate this, as well as to give us the ‘fizz’ and impetus we need to escape danger. The ‘Fight or Flight’ reaction can feel exhilarating in short bursts — it’s why we ride rollercoasters — but it’s not designed to last more than half an hour at the most. Beyond that, it becomes damaging.

Society is currently running tens of thousands of years ahead of evolution. Our ‘Fight or Flight’ reaction is designed to help us flee lions — but it’s being activated by the demands of overbearing bosses. A reaction which is supposed to last mere minutes before being drained out by physical exertion is lasting for hours, days, weeks, even months. And that’s simply appalling for our health [6].

What should happen is that our sympathetic nervous system should naturally cede control to our parasympathetic nervous system once the danger is past, and the ‘Rest and Digest’ system would smoothly get our bodies and minds back to the healthy activities of digesting food, healing injuries, and processing memories, experiences, and other psychological issues. We can — with a little ingenuity — trigger a ‘Fight or Flight’ reaction in ourselves (ruminating on something stressful will do it admirably). Can we do the same for a ‘Rest and Digest’ reaction? We didn’t used to think so — but new studies into the vagus nerve are bringing up evidence to the contrary.

Working ‘Backwards’

Our ‘Fight or Flight’ and ‘Rest and Digest’ systems are, in conventional wisdom, launched by the brain in response to external triggers (or lack thereof). Our muscles, digestion, cardiovascular system, endocrine system and so on are told what to do by messages carried from the brain by our nerves, and they respond accordingly. Many people believe that this is a one-way system – messages come from the brain, and the organs obey. However, evidence increasingly shows that it can work the other way as well.

For centuries, Buddhists and meditational practitioners have spoken of ‘finding your center’ — that area of calm inside yourself from which you can gather and control your sense of self. Scientists have found something similar to the ‘center’ in the vagus nerve. It’s not a perfect analogy, but it does seem that the ability to locate and work with your vagus nerve is just as effective at ‘centering’ you as taking a sedative. And you can achieve this with Buddhist meditative techniques.

Essentially, the Vagus Nerve reverses the flow of information — rather than orders flowing from your brain to your body, the nerve is instead taking some very strong suggestions from the body back to the brain. And, nine times out of ten, the brain listens. By lowering your breathing rate, your Vagus Nerve notes that things must be calm — you have no reason to be breathing hard and fast, and must therefore be able to relax. As it travels around your body and receives ‘relaxed’ messages from those organs over which you do have conscious control while meditating (your lungs, principally, but also your heart to a certain extent), it will infer that you are in no immediate danger, and have no need, therefore, to be stressed. It will convey this message to the brain, which (nine times out of ten) will then ease control over the to parasympathetic nervous system, allowing you to relax, rest, and digest.

When the parasympathetic nervous system has control, we are capable of deeper thought than we are when the sympathetic nervous system is in control (when our immediate survival is not at stake, the brain is more willing to afford time to deep thought). This perhaps explains why the deep breathing and physical relaxation aspects of meditation facilitate such excellent contemplation and self-exploration.

For helpful stories on “how to” meditate, here are some recent features on Buddha Weekly:

Mind/Body Connection

Western philosophy has long struggled with a marked dichotomy between the mind and the body. Since the time of the Ancient Greek’s, we’ve tended to believe that the mind and the body are separate entities, capable only of communicating with each other, but not really intrinsically linked. Furthermore, the mind has been held to be the body’s superior — something which not only controls the body, but can and should be used to suppress it in many cases.

This ‘Mind-Body Distinction’ [7] can hold itself responsible for a host of modern ills, not least among them being the idea that it doesn’t matter what we do with our bodies, and that giving into bodily desires is shameful. To this, we can trace (in some manner) obesity, sexual shame, and a whole host of other issues.

Buddhists in general, by contrast, know that the mind and body are parts of a coherent whole, which influence one another and are vital to one another’s wellbeing. Our growing scientific knowledge about the role that the vagus nerve and how interdependent body/mind really area, may allow for a more holistic view of the entire human, perhaps leading to a healthier, more respectful attitude towards our bodies.

Of course, it is likely to take a very long time to change a concept as ingrained as the mind-body distinction, but we can perhaps use our knowledge of the vagus nerve’s operation in relation to meditation to help those who are dubious about the benefits of ancient Buddhist meditation.

It should be remembered that any reaction to meditation is a highly individual thing, and the kind of deep self-knowledge promoted by intensive meditational programs may not be suitable for everyone [8]. However, as we learn more, we can hopefully work on ways in which to utilize Buddhist techniques in individualized ways which can help more of those in need.

For an interesting story profiling research on mind mapping using “Brain Stress Test”, see this Buddha Weekly Story:

Putting Compassion on the Scientific Map

For practical mindfulness methods, please see these recent features from Buddha Weekly:

NOTES

[1] Julie Corliss, “Mindfulness meditation may ease anxiety, mental stress”, Harvard Health Publications, Jan 2014

[2] Michael Behar, “Can the Nervous System Be Hacked?”, The New York Times Magazine, May 2014

[3] Mercola, “Mental Health Disorders Now Leading Cause Of Non-Fatal Illness Worldwide”, Mercola, Sept 2013

[4] Judson Brewer, “Is Mindfulness an Emerging Treatment for Addiction?”, Rehabs.com, Aug 2014

[5] Philip Low, “Overview of the Autonomic Nervous System”, Merck Manuals

[6] American Psychological Association, “How stress affects your health”

[7] Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, “Rene Descartes: The Mind-Body Distinction”

[8] Miguel Farias, “Meditation is touted as a cure for mental instability but can it actually be bad for you?”, The Independent, May 2015

2 thoughts on “The Science Of Your Center: The Vagus Nerve, Your Meditation Highway, And The Parasympathetic Nervous System; How Meditation Works Positively on the Body”

Leave a Comment

More articles by this author

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Anne Green

Author | Buddha Weekly

Sciatic Nerve is the longest nerve in the human body, not vagus. It’s a great nerve though.

Thank you for your correction.