Why is Following a Guru Difficult to Accept in the West? Why is it Important for Vajrayana Practitioners to Find an Enlightened Teacher?

“We must rely on a wisdom teacher because, although we have Buddha nature, ultimate wisdom does not exist in our dualistic minds. Samsaric ego always tries to protect itself, and will trick us into thinking that we have gone beyond dualistic mind when we have not. Although we intrinsically have Buddha nature, without a teacher, it is like churning water to get butter – it won’t happen.”

— Lama Tharchin Rinpoche, Vajrayana Foundation Sangha [1]

The first time I walked into a Vajrayana Dharma center—long before I accepted a Guru—I witnessed and participated in “lack of respect” for the Guru. I was, until then, a “practicing” Mahayana Buddhist, although by practicing I really mean “searching.”

I was at the Dharma center for a visit from His Holiness the Shakya Trizin, and I was as stiff and unaccepting as most of the other people seemed to be. Tibetans in the large crowd fell to their knees and did full prostrations the moment His Holiness entered. Westerners, like myself, either slightly bowed our heads, or did nothing to honor his entrance.

Culturally, perhaps, we’re not equipped for the concept of the honoring the guru—and in particular, prostrations—in the west. In fact, horror stories of various cults, have made us collectively wary of the word Guru. Democracy and the freedoms we take for granted, make many of us allergic to the entire very idea of Guru, which implies submission.

Submission is a loaded word, and more correctly, in Buddhism, we don’t think of submission, but rather surrender. Sallie Jiko Tisdale, in an interview in the Spring 2014 Buddhadharma [6] described it this way. “I have learned over the years that there is a big difference between submission and surrender.” Surrender of ego, and giving up of cravings, clinging and other causes of suffering are important in most Buddhist practices. If we surrender to our teacher’s guidance, we’re not being submissive. We’re opening ourselves to the teaching process.

Video of full prostration by Venerable Thubten Chodron:

The Concept of Guru

Not only is it difficult to find a qualified Vajrayana teacher in North America and Europe, Westerners tend to have difficulty with the entire concept of a Guru. It’s not a matter of respect, or even affection. Most Buddhists, of any stream, respect—even adore—their teachers. We respect their knowledge, experience, teaching ability, compassion and kindness. But that respect isn’t unconditional. In the Vajrayana tradition, where the Guru is paramount, this attitude generally isn’t enough.

According to Bo-Do-Wa’s Method of Explaining: “…the excellent teacher is the source of all temporary happiness and certain goodness… For attaining freedom there is nothing more important than the Guru…” [5]

“The whole principle of the guru is directly connected with the realization that the Buddha is everywhere,” wrote Frank Berliner in Falling in Love with a Buddha (All My Relations, 2012). “The Guru keeps pointing us toward our own enlightened potential by effortlessly reflecting back to us both our own confusion and our wisdom with every encounter.” [6]

Perhaps for this reason, especially in Vajrayana, students are expected to see our Guru as the living representation of Enlightenment, as the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha all in one. This level of devotion is easier to accept in some eastern cultures—influenced by centuries of Buddhist, Hindu, Daoist and even Confucian beliefs. The bow to an elder, senior or teacher is very normal. In the west, it is often rejected out of hand as submissive. Our collective struggle for democracy and equality makes the entire concept of a Guru awkward and uncomfortable for many—and the full prostration unthinkable to many students.

Lama Tharchin Rinpoche, in an open letter to his Sangha, explained: “While it is true that the appearance of Buddhism naturally changes from country to country, its essence should not change. It is this essence which is so important to transmit by wisdom teachers who are not acting from confusion mind. It seems that people in this country are so eager to dispense with what they view as Asian culture and develop their own form of Buddhism that they do not recognize that they are holding strongly to their own culture. Reliance on a spiritual teacher is not cultural. It is essential.”

Vajrayana incorporates many levels of practice including tantric. The revered Lama Yeshe wrote:

“The need for such an experienced guide is crucial when it comes to following tantra because tantra is a very technical, internally technical, system of development. We have to be shown how everything fits together until we actually feel it for ourselves. Without the proper guidance we would be as confused as someone who instead of getting a Rolls Royce gets only a pile of unassembled parts and an instruction book. Unless the person were already a highly skilled mechanic, he or she would be completely lost.” [4]

If “Master” is Acceptable in Martial Arts…

Guru is difficult enough. It really implies a revered teacher. In earlier times, we might have called our Guru “master”—which, in the west would be an even bigger obstacle to acceptance. Why it’s acceptable in a martial arts dojo, where the teacher is often addressed as Sifu (master), but not for a teacher of lineage in Buddhism is another discussion? Do we respect the black belt more than the enlightened Guru?

Prostrations Difficult to Accept?

The idea of accepting—and honoring—a Guru can be difficult for students to accept. Even once we accept this, we feel very awkward as we fall to our knees to show our full respect. The full prostration, where the entire body is prone, is nearly unimaginable to many people.

Yet, we bow to the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha. The teacher is representative of the Sangha’s highest ideal, and teaches the Dharma, helping lead us to our own Enlightenment. Surely, that’s worthy of more than just a bow? The full prostration also symbolizes submission or obedience, a hard concept to love, although we tend to couch it in terms such as “respect” rather than submission. Still, we are taking vows and submitting to the teachings, and honoring the lineage of our teacher, which in Vajrayana always stretches back to Shakyamuni Buddha.

This level of respect means we must be very careful to pick the right Guru. Venerable Zasep Tulku Rinpoche explains: ” Some people have the fortunate Karma to recognize a good Dharma teacher immediately upon meeting one, but others are full of indecision and doubt, and cannot make up their minds to commit to a particular teacher. They may spend their whole life shopping for the perfect teacher and yet never find him or her.”

Another demonstration of the full prostration:

What’s The Big Deal?

In Buddhism refuge is a critical early step. We are taught to take daily refuge in the three jewels: the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha. The Sangha can be broadly interpreted to include the Sangha of monks, teachers and lamas. Sangha also collectively includes those of us who support each other in the practice as a community, although in this respect, Lama Tharchin Rinpoche, of the Vajrayana Foundation Sangha, cautioned: “…the idea of relying on the ‘collective wisdom of the Sangha’ is dangerous because while Sangha members are on the path, purifying their own minds, they are still rooted in dualistic thinking and confusion. So this Western idea of democracy – which relies on collective consensus from partial, worldly knowledge and opinion – is not the same as the wisdom mind of a teacher holding lineage and realization.”[1]

Why We Need a Guru

The great Lama Tsongkhapa wrote, in The Great Treatise: “Sages do not wash away sins with water, they do not clear away beings’ suffering with their hands, they do not transfer their own knowledge to others; they liberate by teaching the truth of reality.” [5]

According to the website, A View on Buddhism:

“The Buddha compared his teachings to medicine, and the teacher to the doctor who can accurately prescribe the correct medicine for the disciple/patient.” [3]

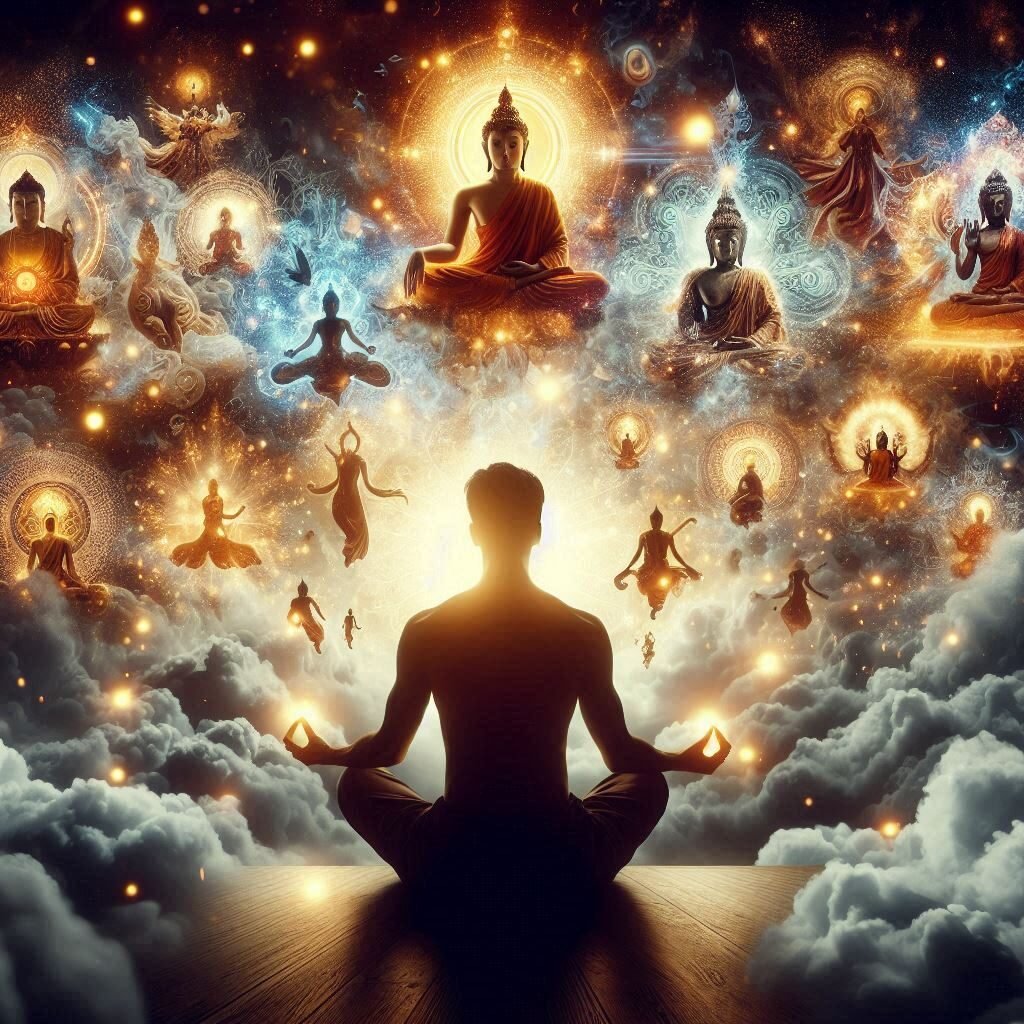

With Vajrayana in particular, the “lightning path” or swift path to enlightenment, we rely on the teacher to take us quickly in the right direction. We don’t just rely on our current teachers, but on an entire lineage. Knowledge passed down through great Mahasiddhas, Bodhisattvas, enlightened teachers—a sure path to understanding the Dharma. Lineage becomes a key element of this. The teachings, and teachers, must be pure. Lineage assures us of this.

Venerable Zasep Tulku Rinpoche explains[2]:

“In the Tibetan Buddhist view, the spiritual teacher is the root of all spiritual realizations and attainments. According to Mahayana and Vajrayana teaching, we should consider our teacher as a Buddha for our own spiritual benefit.” This concept is at the heart of Guru Yoga, which is as problematic with some western students as the simple prostration.

In North America and most of Europe, years of history and culture have ingrained in us a severe individualism—which runs counter to the entire concept of following a Guru. A bow implies subservience in most western cultures. In Buddhism, it implies much more. It symbolizes our refuge in Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. It honors the teachers and teachings. It’s a remedy for pride.

Lama Tharchin Rinpoche explained: “We can see that this worldly approach never leads to unchanging consensus and happiness. Collecting the opinions of confused beings only leads to a larger pile of confusion. For example, Buddhas manifest throughout the six realms according to the needs of beings. We cannot vote for the Buddha who will follow our agenda.”

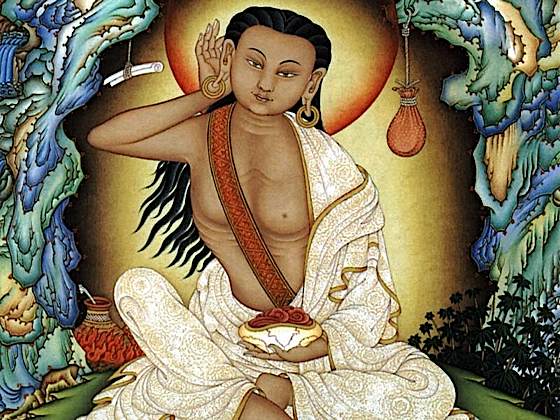

He added a very compelling example. Milarépa, one of Tibet’s most famous yogis, was often thought of as crazy. “We often say that from samsara’s point of view, Milarépa is crazy, and from Milarépa’s point of view, samsara is crazy. If people had been allowed to vote on whether or not Milarépa should be allowed to teach, the answer would probably have been no.”

“If you are only studying Dharma for the sake of study, and the development of your understanding of Dharma, if you are only studying Dharma intellectually, just intellectually on intellectual level, then I don’t think you need a guru-disciple relationship,” explains Venerable Zasep Tulku Rinpoche [3].

“And also you can study with all kinds of teachers. It’s like going to university. You study with different teachers or professors, and you go on, you move on. But if you wish to commit yourself to the path, then [the Guru] is necessary, because one needs to know how to accomplish the realization, how to practice the Dharma.”

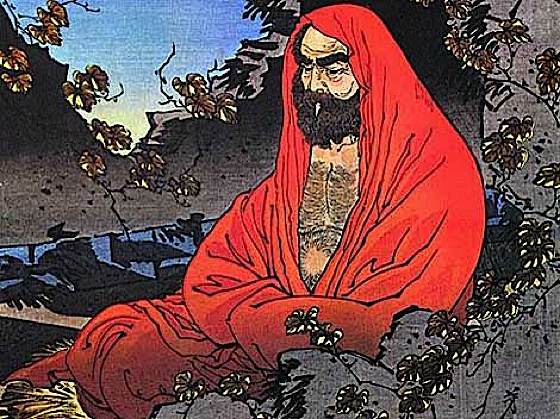

The great Chan Patriarch Bodhidharma, put it this way: “To find a Buddha, all you have to do is see your nature. Your nature is the Buddha. And the Buddha is the person who’s free: free of plans, free of cares. If you don’t see your nature and run around all day looking somewhere else, you’ll never find a Buddha. The truth is, there’s nothing to find. But to reach such an understanding you need a teacher and you need to struggle to make yourself understand…”[3]

Before Accepting a Guru

This discussion is somewhat academic if you can’t find a qualified teacher. Just simply accepting the first teacher you can find—just because it is difficult—as a Guru, is probably risky.

The revered Lama Yeshe wrote: ” For the teachings of enlightened beings to reach us and for their insights to make an impression on our mind, there should be an unbroken lineage of successive gurus and disciples carrying these living insights down to the present day.” [4]

Lama Tharchin Rinpoche advises:

“Before judging, we must know the appropriate qualities of a teacher and examine our own motivation as students. It is critical that the teacher holds pure, unbroken lineage, and has realization of wisdom and compassion for all beings impartially.”

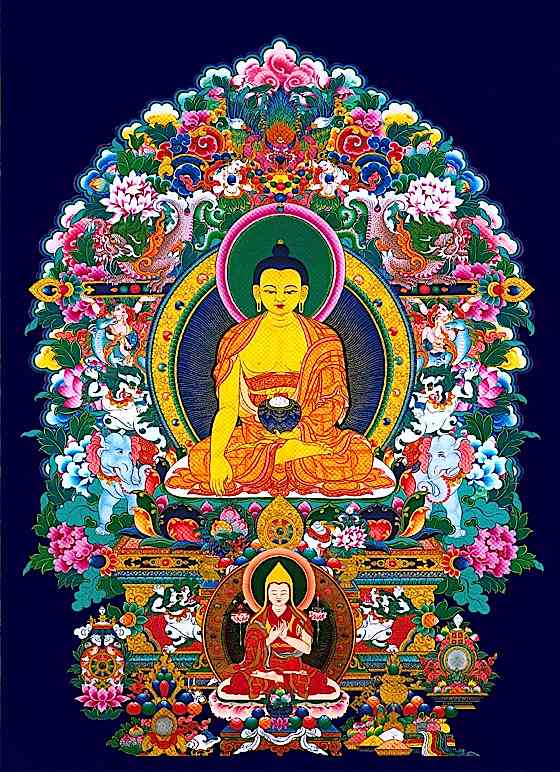

The practice of only accepting Dharma from teachers with a lineage is one of the reasons Vajrayana Buddhists feel comfortable relying on their Guru. We can receive teachings from Enlightened Beings and sages such as Lama Tsonghkhapa, Padmasambhava, and Atisha, by virtue of this unbroken lineage to the Great Conqueror Shakyamuni Buddha.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama has this advice: ” You must investigate before accepting a lama or teacher to see whether that person is really qualified or not.”

In all practice the teacher is important, but in tantric practice a root guru is essential. Lineage is a must in any tantric practice.

Qualifications of a Teacher

The Ornament for the Mahayana Sutras (Mahayana-sutralamkara) describes the ten qualities of an ideal Mahayna teacher: “Rely on a Mahayana teacher who is disciplined, serene, thoroughly pacified; has good qualities surpassing those of the students; is energetic; has a wealth of scriptural knowledge; possesses loving concern; has thorough knowledge of reality and skill in instructing disciples; and has abandoned dispiritedness.” [5]

These qualities of an excellent Guru are, in fact, the very qualities we should seek for ourselves, according to the great Lama Tsongkhapa in his Great Treatise: “These six qualities—being disciplined, serene, and thoroughly pacified, having good qualities…, a wealth of knowledge from studying many scriptures, and thorough knowledge of reality—are the good qualities obtained for oneself. The remaining qualities—being energetic, having skill in instruction, possessing loving concern, and abandoning dispiritedness—are good qualities for looking after others.” [5]

Other things to look for, might include:

1. Lineage back to the Buddha

2. Proper ethical behavior

3. Should have higher realizations than the student

4. Knowledge of the Dharma

5. Compassion

6. Understands and has realized emptiness

7. Skilled means: a skilled speaker able to deliver the Dharma appropriately to students.

What to Avoid

Finding a Guru can take a lifetime. There are dangers. As with anything, there will always be so-called teachers who can mislead students. This is why lineage is important. It’s reliable and verifiable. As with any tradition, there are people who take advantage of religion and authority. It’s best to treat finding a Guru as a life’s mission and take all the time you need.

Once You Find a Teacher

For me it took eleven years of active searching to find my Guru. For some it’s less of an ordeal. For others, they never find their Guru in this lifetime, due to their Karma.

By the time you find such a precious teacher, honoring him or her with full prostrations, service, obedience and enthusiasm seems obvious and automatic.

NOTES

[1] June 1999:A letter from Lama Tharchin Rinpoche to the Vajrayana Foundation Sangha in response to reaction to an interview with Dungse Thinley Norbue Rinpoche in Tricycle Magazine.

[2] Revised Guidelines for the Dharma Students of the Venerable Zasep Tulku Rinpoche Canada, 2013

[3] View on Buddhism, “What is a Spiritual Teacher”

[4] “The Importance of the Guru” by Lama Yeshe

[5] Quoted from The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment by Lama Tsongkhapa.

[6] “Your Teacher and You” Buddhadharama: The Practitioner’s Quarterly, Spring 2014

3 thoughts on “Why is Following a Guru Difficult to Accept in the West? Why is it Important for Vajrayana Practitioners to Find an Enlightened Teacher?”

Leave a Comment

More articles by this author

Who is my Enlightened Life Protector Based on Tibetan Animal Sign Zodiac in Buddhism? According to Mewa, Mahayana tradition and Kalachakra-based astrology (with Mantra Videos!)

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Lee Kane

Author | Buddha Weekly

Lee Kane is the editor of Buddha Weekly, since 2007. His main focuses as a writer are mindfulness techniques, meditation, Dharma and Sutra commentaries, Buddhist practices, international perspectives and traditions, Vajrayana, Mahayana, Zen. He also covers various events.

Lee also contributes as a writer to various other online magazines and blogs.

It is not actually a West vs East issue. Many cEuropean nations are basically similar to the East in many way. The difference is between feudal language systems and planar language (English) systems.

In feudal languages, the verbal code ambiance is essentially pejorative verbal codes vs ennobling. So that, the concept of Guru vs disciple is connected to this.

The disciple has to display subservience and servility. The Guru has the natural right to use pejorative verbal forms to and about the disciple.

The English West cannot understand this. However,some cEuropeans might be able to understand this. For some of the cEuropean nations are feudal language nations which had centuries of proximity to England. That is all.

The clip: The Dalai Lama speaks on Guru devotion” seems to have been hacked. It is a very hateful diatribe against him

Thanks for letting us know David, we removed that clip!