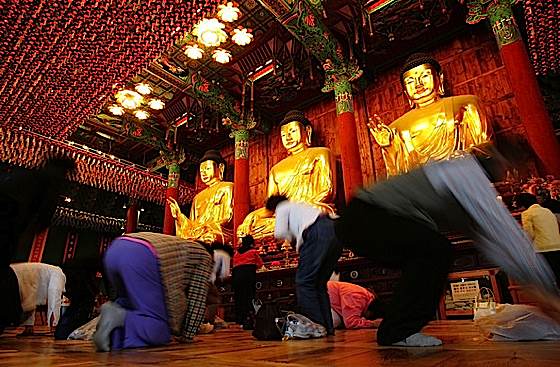

The Foundation Practice of Prostrations: Humble Bow, a Method to Connect with Buddha Nature; the Psychology of Buddhist Prostrations

Psychologically, in modern times, we resist the concept of the bow or prostration. It is considered demeaning. Even the very idea of “bowing” causes our pride to flare up. This is, in fact, its main purpose, at least as a foundation practice in Buddhism. To humble our pride. To trample on our ego. This is not a bad thing, at least in terms of Buddhist practice. Tulku Migmar, on the Samye Institute website, explains:

“Sometimes we may feel uncomfortable with this practice as we see it as merely a custom. Here, Tulku-la reminds us of the profound meaning and the purpose behind prostration. He speaks of the proper visualization as well as the proper motivation that should accompany the practice. We should also understand that our reaction to the practice may be a way of our tricky ego trying to assert itself–prostrations are designed to reduce pride and ego-clinging.”

Many modern Buddhists are hesitant to practice ancient physical methods—prostrations, mudras, physical offerings—and can often only be convinced if they can somehow psychologically rationalize it. For example, deity practice is often “psychologically” categorized as “making a connection with your inner Self”—Buddha Nature in Buddhism, “Self” in Jungian psychology.

However, in most traditions of Buddhism, it is much more than this. In every school, bowing is a critical practice — often called a foundation practice. The earliest Pali Suttas describe laypeople and monks alike “joyously prostrating” to the Buddha.

“Prostrations are a wonderful way of supporting the process of surrender,” writes teacher Rob Preece in Preparing for Tantra: Creating the Psychological Ground for Practice. “As we prostrate to the symbol of the Self, in Jung’s terms, or to our Buddha Nature, we are letting go.” Later in the book, he writes, “The prostration practice does not eliminate the ego, but it does place it into relationship with the clear knowledge that it is secondary to the Self or the deity.”

Note: How-to: at end of this feature.

Psychological Rationalization

For a modern western practitioner, prostrations can be even more difficult to rationalize than offerings and mudras. It’s easy to understand that prostrations “cut the ego.” Intellectually it’s not difficult to accept the teaching that attachment and ego cause suffering. In the case of prostrations, however, it feels like we’re giving up control, a concept modern society has trouble with.

How can modern people, brought up in a ego-centered culture, relate to an ancient show of pride-destroying deference? Whether bowing to the Buddha or the respected teacher, it is difficult for many people who grew up in western-influenced culture to show such humble devotion—particularly in public.

Prostrations to a Teacher

I recently attended a Lojong event, taught by Zasep Tulku Rinpoche, hosted by Gaden Choling in Toronto. When Rinpoche entered, even though we had been “coached” to bow—with a lengthy explanation of why—the majority of guests in the very full audience gave slight bows at best, a nod at worst. Without any hesitation, his formal students fell to the floor—but with a joyful feeling of celebration rather than subservience. They were grateful for the opportunity to listen to this teacher, who had fled Tibet during the occupation, had spent his long life teaching western students the Dharma, who had been himself taught by an illustrious line of very famous gurus. (Buddha Weekly feature on Zasep Tulku Rinpoche>>)

During Tibetan Buddhist formal teachings, when a teacher enters, we bow. If we are a student we would perform full prostrations to our guru. Floor-bound prostrations to a living being—even someone as well respected as the Dalai Lama—can present even more issues for modern Buddhists. We’re now appearing to surrender our control to a human being. Then, if we are watchful, we begin to intuitively understand, when we see that same teacher we just bowed to fall to the floor and prostrate to the Buddha and his own teachers. It goes beyond simple respect and etiquette.

Physical Yoga?

Some of my Buddhist friends, who have difficulty with full prostrations—especially in public venues—try to rationalize the action as “tradition” and sometimes even as a physical yoga, and a healthy exercise.

In a recent teaching on Lojong and the preliminary practices, Venerable Zasep Tulku Rinpoche spoke at length about the traditional, psychological, and even physical reasons for prostrations: “Doing 100,000 full-body-to-floor prostrations sounds difficult, but it’s very good yoga. You will be very healthy after you finish,” he joked. (Buddha Weekly’s coverage of Lojong teaching with Zasep Rinpoche>>)

Of course, Rinpoche explained, physical yoga is not its purpose. It is meant to ruthlessly cut, cut, cut the ego. In the same way Manjushri’s great sword cuts ego and duality, prostrations can be a powerful way to connect to our egoless Buddha Nature.

“As we embark on the spiritual journey, we need to challenge the central status of the ego so that the solidity of its grip can gradually be softened,” writes Rob Preece inPreparing for Tantra: Creating the Psychological Ground for Practice. “The solidity of the self brings with it ego inflation and a loss of relationship to a deeper spiritual core, whether we call it Self or Buddha Nature.”

Prostrations Common to Most Buddhist Paths

Most Buddhist paths include some form of prostrations in daily practice. Traditionally, prostrations are more than a show of respect for Buddha, Dharma and Sangha; they are a method to purify the mind, or the “antidote” for ego-clinging. Cutting the ego down to size is at least somewhat important to helping us understand the wisdom of emptiness. Additionally, in terms of the “five faults” you could also say that prostrations can be an antidote for the fault of “laziness.”

Lama Zopa Rinpoche put it this way: “Making prostrations is an excellent antidote for slicing through false pride.” [1] Prostrations are often encouraged in the context of showing respect for all living beings. Since every sentient being has Buddha Nature (in Mahayana traditions), bowing to any person can be thought of as bowing to the Buddha Nature in all of us.

In Lojong training, cutting the ego through preliminary practices such as prostration is “point one”, while Bodhichitta, is “point two.” Both are critical. The Lojong root text teaches: “Contemplate that as long as you are too focused on self-importance and too caught up in thinking about how you are good or bad, you will experience suffering. Obsessing about getting what you want and avoiding what you don’t want does not result in happiness.” The main preliminary practice focused on cutting the ego is prostrations.

Purification of Body, Speech and Mind

In Tibetan, the word prostration is translated as chak tsal. Chak means to “sweep away” harmful actions and obscurations. Tsal means we receive the blessings of an enlightened body, speech and mind.

“When we do prostrations we act on the level of body, speech, and mind,” wrote Lama Gendyn Rinpoche. “The result of doing them is a very powerful and thorough purification. This practice dissolves all impurities, regardless of their kind, because they were all accumulated through our body, speech, and mind. Prostrations purify on all three levels.”

A Tantric Goal: Working our “Energy Wind Body”

To advanced tantric practitioners, prostrations help us work our subtle bodies—”energy-wind body” as it’s sometimes translated. The energy of the subtle body—known variously as Chi, Prana, Winds—is visualized in this practice.

Author and teacher Rob Preece described his own early work with prostrations: “When I was doing these prostrations in Bodhgaya, there were a number of other Westerners going through the same process nearby, and I could see this emotional upheaval happening in them as well. Some days I was in excruciating pain, while the person next to me was ecstatic, and the next day she was in a flood of tears, and it was my turn to feel ecstatic.” What he was describing was the process of the energy-wind body releasing blocked “toxic energy that had been held so long.” He added, “I could really feel purification was taking place.”

Energy Wind Body, or subtle body, is well accepted in most Eastern traditions, and to some extent by science in the west, via the success of Acupuncture in controlling pain. Rob Preece, who is a working psychologist, also describes Energy Wind Bodies as analogous to emotions, with wind connoting emotion. In my very basic layman’s understanding, for example, guilt or repressed emotional memories might be imprinted on our psyche, sometimes without our explicit knowledge. The famous psychologist, Carl Jung, described this bundle of repressed, unpleasant memories and guilt trips as the “Shadow.” Just like karma seeds in Buddhism, the shadow can ripen and affect us tangibly in our lives, often with tragic consequences. Working with prostrations releases the trapped “winds” or emotions, the collected guilt, thus purifying our karma.

Another way of understanding winds or chi is as subtle energies in the body. Acupuncture, Tai Chi—and prostrations—can work to manipulate or enhance these energies.

Venerable Thubten Chodron physically demonstrates how to do prostrations:

How Many Prostrations?

In some formal preliminary practices, a student might be asked to perform one hundred thousand prostrations. This might be in a single months-long formal retreat at a sacred place. Other teachers, understanding our busy lives, simply ask students to work towards 100,000 through a daily practice of a few each day. The numbers are not significant. They symbolize that constant repetition is the goal to help us advance and subdue the ego.

The well known Feng Shui expert and author Lillian Too — based on teachings from her own guru, Lama Zopa Rinpoche — recommends morning and evening prostrations to help purify karma. She recommends 3 prostrations in the morning and evening at a minimum, and preferably three times 35 in the morning. She recommends the prostration mantra be recited while prostrating:

OM NAMO MANJUSHRIYE, NAMO SUSHRIYE, NAMO UTTAMA SHRIYE SOHA

In the evening, she suggests a further 28 dedicated to Guru Vajrasattava, with Vajrasattva’s mantra, OM VAJRASATTVA HUM.

Proper Motivation

Prostrations may work on pride and ego regardless of motivation, but to most Buddhists the motivation is key to success. Importantly, we set our motivation “to benefit all sentient beings.”

Without the motivation, the practice is purely physical, with some added benefits in taming the ego. When we set the motivation, it becomes a Mahayana Buddhist practice, focused on Bodhichitta—on kindness and regard for all sentient beings. The benefits then become as wide and expansive as the collective of sentient beings.

Lama Gendyn Rinpoche explains it this way: ” When we do prostrations we should understand that good actions are the source of happiness of all sentient beings. Prostrations are a good example of this fact. When we do the practice using our body, speech, and mind, we offer our energy to others wishing that it brings them happiness. We should be happy about this fact and do prostrations with joy.”

How to Prostrate

The body aspect of the practice is purely physical, involving the whole body, and pressing the entire body flat to the ground at the lowest point, in full contact with the earth. The speech aspect is normally the mantra or praise we chant as we prostrate (mentally, or aloud). This can be as simple as “I prostrate to the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha,” or the mantra of a Buddha, deity or teacher you are visualizing. The mind aspect involves visualizing yourself prostrating fully. Mind, is also a result of prostration: diminishing the power of the ego over our mind.

A helpful video from Lobsang Wangdu of YoWangdu Tibetan Culture showing three different styles of prostration:

The steps (in one method for Vajrayana practice) are:

- Visualization: Even if we are bowing to a physical altar, some level of visualization is practiced to fully involve our minds in the practice. Normally, you visualize the Buddha, or your practice deity, or your root guru. In formal prostrations, you might also visualize the entire “merit tree” or “field of merit”—all of the enlightened beings gathered in front of you, surrounding your main practice deity, Buddha or guru.

- Involve All Sentient Beings: One valuable technique for developing Bodhichitta is to visualize all sentient beings around you (in front, beside and behind you), also prostrating. Most people can’t manage a detailed visualization of so many, but the key is to just understand that you are bowing on behalf of ALL sentient beings.

- Speak a mantra or praise: involving “speech” in the prostration. This is normally the OM NAMO MANJUSHRIYE, NAMO SUSHRIYE, NAMO UTTAMA SHRIYE SOHA prostration mantra (for Vajrayana practitioners), or a deity or Buddha mantra, such as the Chan Buddhist “Namo Amitabha” or “Amituofo” or a deity mantra such as OM MANI PADME HUM (Avalokiteshvara’s mantra). Many recite the all-important daily refuge as they do their prostrations: “Until I reach enlightenment I take refuge in the Three Jewels: Buddha, Dharma and Sangha.”

- Clasp the hands together above the head. As we draw the hands down to touch our head we visualize light purifying our bodies of all its obscurations and negativities. (If you can’t visualize, simply understand that your body is symbolically purified by the action.)

- As we draw down our clasped hands to our throat level, we visualize light purifying our speech.

- As we draw down our clasped hands to our heart level, where traditionally our mind resides, we visualize or understand that our mind is purified.

- Five-Point-Prostration: We quickly kneel, and our head touches the floor, so that now our knees, hands and head are touching the earth in five places. We visualize or understand that our five negative or disturbing emotions—anger, attachment, ignorance, jealousy, and ignorance—are leaving our body and flowing into the earth. This final act symbolically completely purifies us.

- Some people stop at the Five-Point-Prostration, while many continue to the full body prone prostration, sliding forward until their entire body is in contact with the earth. This is the “big” purification” through the surrender of ego. In some Buddhist traditions, we turn up our hands, our fingers pointing skywards with our wrist still pressed to the ground. In other traditions, we turn over our hands, palm up, symbolically representing us “holding up the precious feet of the Buddha.”

- Without hesitation we rise up and begin the next prostration.

NOTES

[1] Making Prostration, Lillian Too

[2] Preparing For Tantra: Creating The Psychological Ground For Practice by Rob Preece Publisher: Snow Lion (Sept. 16 2011) ISBN-10: 1559393777 ISBN-13: 978-1559393775

4 thoughts on “The Foundation Practice of Prostrations: Humble Bow, a Method to Connect with Buddha Nature; the Psychology of Buddhist Prostrations”

Leave a Comment

More articles by this author

Protection from all Harm, Natural Disaster, Weather, Spirits, Evil, Ghosts, Demons, Obstacles: Golden Light Sutra: Chapter 14

Guru Rinpoche is ready to answer and grant wishes: “Repeat this prayer continuously” for the granting of wishes

VIDEO: Vajrapani Vajra Armor Mantra: Supreme Protection of Dorje Godrab Vajrakavaca from Padmasambhava

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Lee Kane

Author | Buddha Weekly

Lee Kane is the editor of Buddha Weekly, since 2007. His main focuses as a writer are mindfulness techniques, meditation, Dharma and Sutra commentaries, Buddhist practices, international perspectives and traditions, Vajrayana, Mahayana, Zen. He also covers various events.

Lee also contributes as a writer to various other online magazines and blogs.

I have yet to find the writings of the names of the 35 Buddhas. How can I find the text o memorize?

Are you looking for the Sanskrit Names or the English translated names or Tibetan? According to most teachers, either is fine. The Sanskrit is obviously harder to memorize, but it has a different feeling when reciting. I have all three, glad to send them if you let me know which you’d prefer.

You’ve inspired a story idea, so please watch for a feature on 35 Buddhas.

I’ll paste this in, hoping it formats okay, which shows the different names in Sanskrit (left) Tibetan and English, but we’ll try and file a story on this this week:

Śākyamuni ཤཱཀྱ་ཐུབ་པ་ shakya tup-pa Shakyamuni

Vajrapramardī རྡོ་རྗེ་སྙིང་པོས་རབ་ཏུ་འཇོམས་པ dorjé nyingpö raptu jompa Thoroughly Conquered with Vajra Essence

Ratnārśiṣ རིན་ཆེན་འོད་འཕྲོ rinchen ö-tro Radiant Jewel

Nāgeśvararāja ཀླུ་དབང་གི་རྒྱལ་པོ luwang gi gyelpo King, Lord of the Nagas

Vīrasena དཔའ་བོའི་སྡེ pawö-dé Army of Heroes

Vīranandī དཔའ་བོ་དགྱེས pawö-gyé Delighted Hero

Ratnāgni རིན་ཆེན་མེ rinchen-mé Jewel Fire

Ratnacandraprabha རིན་ཆེན་ཟླ་འོད rinchen da-ö Jewel Moonlight

Amoghadarśi མཐོང་བ་དོན་ཡོད tongwa dönyö Meaningful Vision

Ratnacandra རིན་ཆེན་ཟླ་བ rinchen dawa Jewel Moon

Vimala དྲི་མ་མེད་པ drima mépa Stainless One

Śūradatta དཔའ་སྦྱིན pa-jin Glorious Giving

Brahma ཚངས་པ tsangpa Pure One

Brahmadatta ཚངས་པས་སྦྱིན་ tsangpé jin Giving of Purity

Varuṇa ཆུ་ལྷ chu lha Water God

Varuṇadeva ཆུ་ལྷའི་ལྷ chu lhaé lha Deity of the Water Gods

Bhadraśrī དཔལ་བཟང pel-zang Glorious Goodness

Candanaśrī ཙན་དན་དཔལ tsenden pel Glorious Sandalwood

Anantaujas གཟི་བརྗིད་མཐའ་ཡས ziji tayé Infinite Splendour

Prabhāśrī འོད་དཔལ ö pel Glorious Light

Aśokaśrī མྱ་ངན་མེད་པའི་དཔལ་ nyangen mépé pel Sorrowless Glory

Nārāyaṇa སྲེད་མེད་ཀྱི་བུ sémé-kyi bu Son of Non-craving

Kusumaśrī མེ་ཏོག་དཔལ métok pel Glorious Flower

Tathāgata Brahmajyotivikrīḍitābhijña དེ་བཞིན་གཤེགས་པ་ཚངས་པའི་འོད་ཟེར་རྣམ་པར་རོལ་པ་མངོན་པར་མཁྱེན་པ dézhin shekpa tsangpé özer nampar rölpa ngönpar khyenpa Pure Light Rays Clearly Knowing by Play

Tathāgata Padmajyotirvikrīditābhijña དེ་བཞིན་གཤེགས་པ་པདྨའི་འོད་ཟེར་རྣམ་པར་རོལ་པས་མངོན་པར་མཁྱེན་པ dézhin shekpa pémé özer nampar rölpé ngönpar khyenpa Lotus light Rays Clearly knowing by Play

Dhanaśrī ནོར་དཔལ norpel Glorious Wealth

Smṛtiśrī དྲན་པའི་དཔལ drenpé pel Glorious Mindfulness

Suparikīrtitanāmagheyaśrī མཚན་དཔལ་ཤིན་ཏུ་ཡོངས་སུ་གྲགས་པ tsenpel shintu yongsu drakpa Renowned Glorious Name

Indraketudhvajarāja དབང་པོའི་ཏོག་གི་རྒྱལ་མཚན་གྱི་རྒྱལ་པོ wangpö tok-gi gyeltsen-gyi gyelpo King of the Victory Banner that Crowns the Sovereign

Suvikrāntaśrī ཤིན་ཏུ་རྣམ་པར་གནོན་པའི་དཔལ shintu nampar nönpé pel Glorious One Who Fully Subdues

Yuddhajaya གཡུལ་ལས་རྣམ་པར་རྒྱལ་བ yül lé nampar gyelwa Utterly Victorious in Battle

Vikrāntagāmī རྣམ་པར་གནོན་པའི་གཤེགས་པའི་དཔལ nampar nönpé shekpé pel Glorious Transcendence Through Subduing

Samantāvabhāsavyūhaśrī ཀུན་ནས་སྣང་བ་བཀོད་པའི་དཔལ kün-né nangwa köpé pel Glorious Manifestations Illuminating All

Ratnapadmavikramī རིན་ཆེན་པདྨའི་རྣམ་པར་གནོན་པ Rinchen padmé nampar nönpa Jewel Lotus who Subdues All

Ratnapadmasupraṭiṣṭhita-śailendrarāja དེ་བཞིན་གཤེགས་པ་དགྲ་བཅོམ་པ་ཡང་དག་པར་རྫོགས་པའི་སངས་རྒྱས་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་དང་པདྨ་ལ་རབ་ཏུ་བཞུགས་པའི་རི་དབང་གི་རྒྱལ་པོ Dézhin shekpa drachompa yangdakpar dzokpé sanggyé rinpoché dang padama la raptu zhukpé riwang gi gyelpo All-subduing Jewel Lotus, Arhat, Perfectly Completed Buddha, King of the Lord of the Mountains Firmly Seated on Jewel and Lotus

Can you tell which part of the body corresponds to the each of the five mental poisons? Thank you 🙂

Thank you a very good question. Here I’ll cite Gosok Rinpoche, and a general summary:

• Forehead:

Touching the forehead to the ground symbolizes the purification of ignorance, which is a key element in the practice.

• Two Palms:

Touching the palms to the ground represents the purification of attachment and hatred.

• Two Knees:

Touching the knees to the ground symbolizes the purification of jealousy and pride

“The practice of prostrations is part of the seven limb offering, which focuses on accumulating merit and purifying negativities. “Accumulating merit” refers to gathering wisdom and merit, while “purifying negativities” means cleansing the karmic obstacles accumulated over countless lifetimes. Whether a practitioner’s mind can generate realizations depends on their practice of accumulating merit and purifying negativities. Without such practices, no realizations will arise in the mind.

Three Types of Prostrations: Body, Speech, and Mind

The first branch of the sevenfold offering is “prostration,” which can be performed through body, speech, and mind:

• Prostration of the body : Physically bowing down to the Buddha.

• Prostration of speech : Praising the virtues of the Buddha with words.

• Prostration of the mind : Generating unwavering faith in the Buddha.

Whether practicing according to the seven limb offering or performing full prostrations, one must follow the methods taught by the lineage masters. Only by practicing correctly can one achieve the goal of accumulating merit and purifying negativities.

Proper Method of Prostration

To perform prostrations properly, begin by placing your palms together with your thumbs tucked into the center of your palms. The hollow space in the palms symbolizes the dependent origination of emptiness, which is crucial for future spiritual attainments. This practice creates the causes for obtaining a precious human rebirth during the time of the Buddha’s teachings or even after his passing.

1. Palms at the crown of the head (or forehead) : This generates the cause for attaining the Buddha’s perfect physical form, including the 32 major marks and 80 minor signs of enlightenment. Placing the hands here specifically creates the cause for attaining the Buddha’s ushnisha (crown protuberance) or the white hair between the eyebrows.

2. Palms at the throat : This creates the cause for attaining the Buddha’s 60 melodious qualities of speech.

3. Palms at the heart : This creates the cause for realizing the Buddha’s omniscient mind, known as “all-knowing wisdom.”

Next, place your hands on the ground, kneel, and touch your forehead to the ground, completing the five-point prostration (hands, knees, and forehead). This method follows the Vinaya’s guidelines on karma. Every detail must be performed correctly; otherwise, the prostration may still accumulate merit but will have deficiencies. For example, offering a flower to the Buddha brings great merit, but if the flower is wilted, it diminishes the offering. Similarly, improper prostrations create negative conditions that practitioners should avoid.

Counteracting Pride

When performing full prostrations, the essence of the practice lies not just in physical actions or verbal recitations but in generating sincere faith and devotion. Future attainments depend on whether this faith is present. By practicing prostrations correctly, one not only accumulates the virtues of the Buddha’s body, speech, and mind but also counteracts pride — one of the five poisons (attachment, anger, ignorance, pride, and doubt).

Pride arises when we cannot place others above ourselves. In prostrations, the highest part of our body — the head — touches the ground, which is the lowest point. By doing so, we humble ourselves and elevate the object of our prostration, thereby purifying the karmic obstacles created by pride across countless lifetimes.

Objects of Prostration

The objects of prostration should not be limited to Buddhas and bodhisattvas. All sentient beings deserve our respect and prostration. As stated in a sutra prayer: “May I always remain humble and place all sentient beings above me.” Our existence and well-being depend on the kindness of sentient beings. Whether seeking temporary happiness in this life or ultimate liberation and Buddhahood, we rely on other sentient beings.

For example, to perfect the six perfections (generosity, discipline, patience, effort, concentration, and wisdom), we need sentient beings as objects for practice. Without them, how could we practice giving, uphold precepts, or cultivate patience? Reflecting on the kindness of sentient beings naturally generates respect and gratitude toward them.

Benefits of Prostrations

A Tibetan proverb says: “On a proud rock, no drop of water can stay.” Just as rain cannot collect on a steep mountain, practicing with arrogance prevents us from retaining any merit. To accumulate merit, we must counteract pride by remaining humble and honoring the Buddha, Dharma, Sangha, and sentient beings.

Performing full prostrations creates vast merit. In the future, one will attain the immeasurable virtues of a chakravartin, a king who turned the wheel of dharma, one who possesses immense merit and is respected by gods and humans. The merit gained from full prostrations far exceeds that of shorter prostrations because the area covered by the body during full prostrations is much greater.

Additionally, prostrations help purify the infinite negative karma accumulated over countless lifetimes in samsara. While practicing, visualize countless bodies representing your past lives performing prostrations simultaneously. This aligns with the aspiration of Samantabhadra Bodhisattva, who vowed to manifest as many bodies as there are particles of dust on Earth, prostrating to the Buddhas of the ten directions and purifying past misdeeds.

Integrating the Six Perfections

If one integrates the six perfections into the practice of prostrations, the benefits become even more profound:

1. Generosity (Dana) : Encourage sentient beings to take refuge in the Three Jewels and practice prostrations. Guiding others to practice generates immense merit, even if you lack time for personal practice. For example, if you guide someone to take refuge and they diligently practice, their merits will indirectly benefit you as well.

2. Ethics (Sila) : Performing prostrations according to the proper method constitutes ethical discipline. Avoid selfish motives and dedicate the practice to benefiting all sentient beings, helping them overcome suffering and attain happiness. Discipline also involves reflecting on the impermanence of life and the rarity of encountering the Dharma.

3. Patience (Ksanti) : When physical pain or fatigue arises during prostrations, endure it with patience and continue practicing without distraction. Recognize that these difficulties are opportunities to purify negative karma and develop resilience.

4. Perseverance (Virya) : Rejoice in the opportunity to practice prostrations as a human being who has taken refuge in the Three Jewels. Consider how rare this opportunity is compared to beings in lower realms, and practice with joy and diligence. Reflect on the countless beings trapped in the hell, hungry ghost, or animal realms who cannot even hear the Dharma, let alone practice prostrations.

5. Concentration (Dhyana) : Focus your mind entirely on the object of prostration. Avoid distractions caused by attachment, worry, or meaningless thoughts. Concentration ensures that the practice is effective and that its benefits are maximized.

6. Wisdom (Prajna) : Understand the nature of prostrations and their benefits. Reflect deeply on the emptiness of the three spheres—the prostrator, the object of prostration, and the act of prostration—and realize their dependent origination. Wisdom arises when one understands that all phenomena are empty of inherent existence yet appear due to interdependent causes and conditions.

Four Characteristics of Prostrations

In summary, prostrations have four key characteristics:

1. The number of sentient beings performing prostrations is immeasurable.

2. The number of Buddhas and bodhisattvas being prostrated to is immeasurable.

3. The number of bodies one has taken in samsara is immeasurable.

4. The number of prostrations performed is immeasurable.

Thus, the merit accumulated is boundless. May all practitioners diligently engage in this practice!”

Gosok Rinpoche http://gosokrinpoche.com/merits-of-prostrations/