The Jataka Tales: Why they remain relevant for adults and children both; all of the Buddhist Teachings contained in stories

The word “Jataka” means “birth” in both the Pali and Sanskrit languages. The Jataka tales, among the oldest and best known of Buddhist texts, refers to stories of the past lives of Siddhartha Gautama before he became the Buddha in his final life.

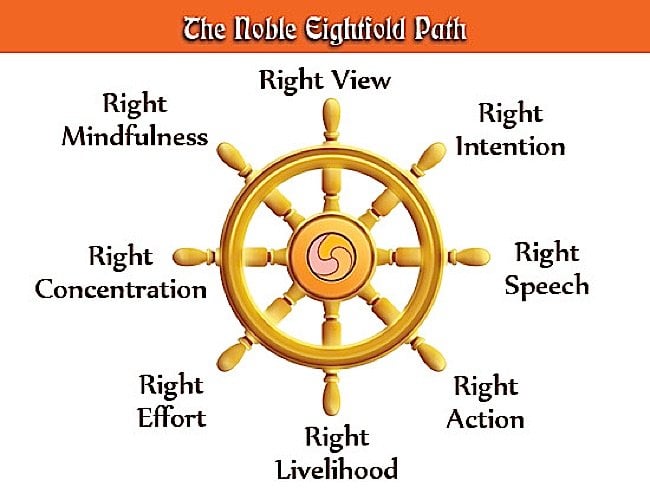

These charming and helpful stories number in the hundreds, with each life illustrating different teachings: the Paramitas, the Four Noble Truths, the Bodhisattva Vows, the Eightfold Path, the Four Abodes, the Six Realms —all engagingly taught in the form of life stories. Each features the Buddha in diverse forms: he appears as an animal, a king, a wandering ascetic, a monkey and much more.

Feature by Lee Clarke

[Bio at bottom]

The Starving Tigress: self-sacrifice

The most famous of these stories is the story of “The Starving Tigress” — a story that teaches ultimate compassion, Bodhichitta, and self-sacrifice:

“Born into a family of Brahmans renowned for their purity of conduct and great spiritual devotion, the bodhisattva (future Buddha) became a great scholar and teacher. With no desire for wealth and gain, he entered a forest retreat and began a life as an ascetic. It was in this forest where he encountered a tigress who was starving and emaciated from giving birth and was about to resort to eating her own new born cubs for survival. With no food in sight, the bodhisattva, out of infinite compassion, jumped off the cliff, landing in front of the starving beast, and offered his body as food to the tigress, selflessly forfeiting his own life.” 4

Jatakas: among the earliest Pali Buddhist texts

The Jatakas are actually among the earliest Buddhist literature and are accepted by all branches and traditions of Buddhism as valid.

In the Buddhist tradition, just before reaching enlightenment, the Buddha saw clearly, all his past lives — and the faithful accept that the Jatakas are literally his past lives. One can believe, based on faith, that the stories came from the Buddha’s own mouth. Others view the Jakatas as teaching stories. Whether they are accepted as literally true, or metaphorical stories, either way, they are wonderful teachings: used for countless centuries to teach children, adults, laypeople, and monastics. Of course, scholars tend to come down on the side of teaching myths — which makes no difference to their relevancy.

Sarah Shaw writes:

“…the tales comprise one of the oldest and largest collections of stories in the world. The earliest sections, the verses are considered amongst the very earliest part of the Pali tradition and date from the fifth century BCE…”.[1]

From a scholarly point of view, how the Jatakas developed individually is somewhat obscure but it is speculated as a whole that they arose due to curiosity about the Buddha’s past lives. For example, Shulamit Ambalu et al say:

“Given the general Indian belief in reincarnation, it was not long before people started to speculate about Buddha’s previous lives, and the actions and characteristics he must have displayed in those lives to move towards Nirvana. These musings led to the compilation of the Jataka tales or “Birth Stories”.[2]

Beautiful stories with profound teachings

If for no other reason, Jatakas should be read are simply because they are beautiful works of literature. They have a numerous and memorable cast of characters, powerful imagery and always include a moral at the end to reflect upon. They normally start with the Buddha relating a contemporary situation facing him to a similar one that faced him in a past life, at the end of the stories, he then says who the characters represent in real life.

As works of religious literature, they are similar to the secondary literature of other faiths, most notably the Hindu Puranas which depict faith-inspiring folk stories of the Hindu gods, such as Krishna. They are also similar to the Islamic Hadith which is the actions and sayings of the Prophet Muhammad that provides an example to Muslims.

The main thing I love about the Jatakas — and the main idea I think most Buddhists take from them — is that they bring the Buddha fundamentally down to our level; that is, the level of ordinary Buddhists.

In the main body Pali Suttas, and in Mahayana Sutras, we are so used to seeing the Buddha as beyond ordinary. Even though he was a human, of course, the main image of the Buddha tends to be this image of a great being who attained supreme Enlightenment through his own intelligence, integrity, and effort. Whilst this view of him is true, he can sometimes seem somewhat out of reach of ordinary lay Buddhists.

Jakarta’s are approachable, human (or nonhuman) stories

In many of the Jatakas, by contrast, the Buddha starts the tale by saying “When I was just an unenlightened Bodhisattva”. By saying this, the Buddha is bringing himself down to our level. This gives us hope that we, as humans, can aspire to Enlightenment.

With his glorious image as sage and Enlightened Being, we can sometimes forget that he was human, and that, before he became the Buddha, he was just like us. A being, trapped in the continuous cycle of samsara taking birth again and again in different forms in order to reach enlightenment.

Epic beginning: Dipankara Buddha sees the future Buddha Siddhartha

Tradition says that Siddhartha Gautama, in a previous life, eons ago, was a man named Sumedha. The Buddha of that time, Dipankara Buddha, foresaw that Sumedha would become Shakyamuni Buddha after many lives. Sumedha made the vow that he would achieve this great goal — and thus the Jatakas begin.

We can take from the Jatakas a reminder that the Buddha was once exactly the same as us — and that we can all reach enlightenment just like he did. Also, a reminder that it isn’t easy. The Jatakas remind us of our inherent Buddha Nature, universal to all sentient beings.

The tales, also provide us with indirect examples of the Eightfold path — rich action, right speech, right thought, right understanding, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, right concentration — all are beautifully illustrated in the stories. In his former lives, Buddha is depicted as every type of being: king, peasant, man, woman, lower caste and higher caste, animals, tradesman, ship’s captain. This transcends time, and remain contemporary and approachable even today.

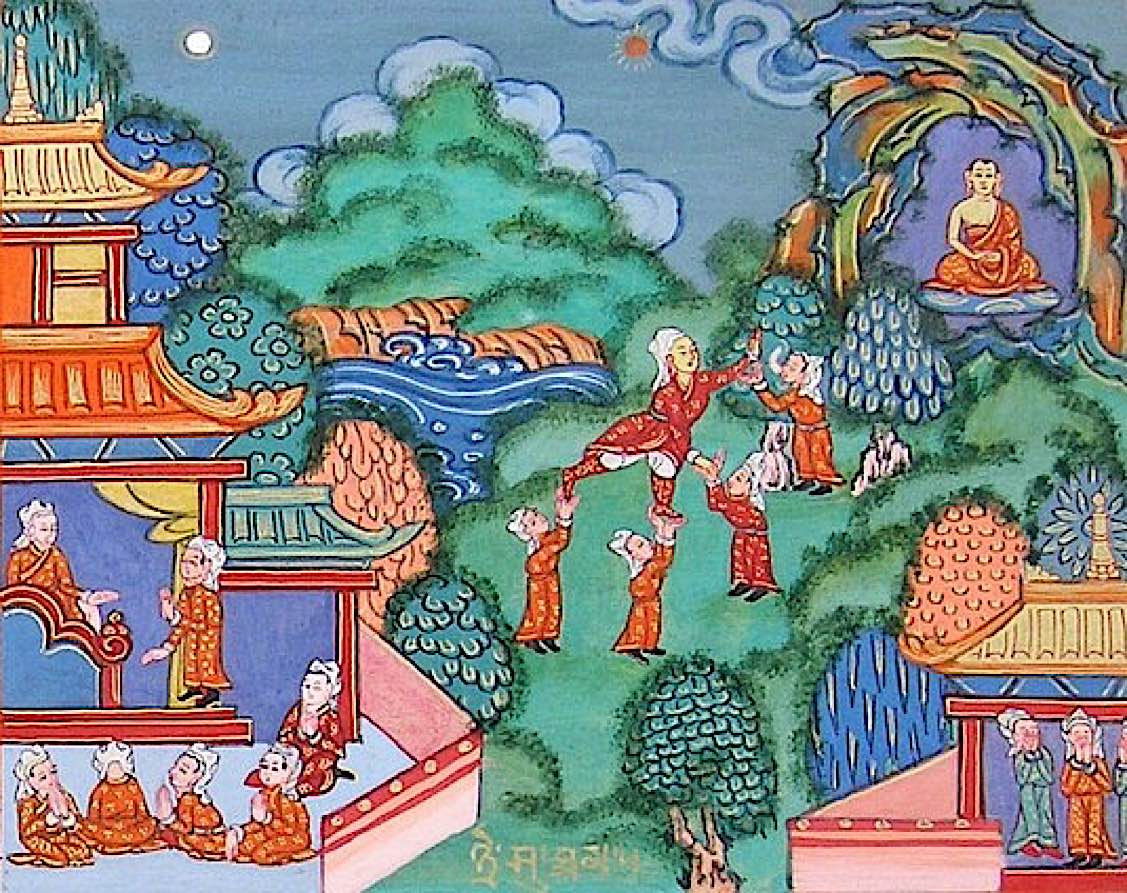

Buddha previously lived in many forms of animal and human: the Monkey King

In each short life story, the Buddha, in his previous incarnations, performs an act that demonstrates a key Buddhist quality such as compassion, wisdom, self-sacrifice, and loving-kindness. Since we see the Buddha Himself lived as every form of life, it helps teach us we should respect all life. In Buddhist belief, all sentient life has Buddha Nature, and any form of life could be a potential Bodhisattva.

In the Jakata Tales, he lived as a hare, woodpecker, ruru deer, monkey king, elephant, buffalo, and many others. In the tale of the Monkey King, the theme is leadership and self-sacrifice:

“The Bodhisattva however, seeing that his frightened subjects were depending on him, reassured the group. Quickly climbing to the top of the tree, and in one giant leap, he flew to a nearby hilltop where he found a bamboo cane that was tall, strong, and deeply rooted. Fastening the top of the cane to his feet, and leaving it rooted in the earth, he jumped back to his tree home. Holding a branch of the tree taught, he ordered all the monkeys to evacuate across his body and down the cane to safety. Desperate and bewildered by fear, the monkeys wildly scrambled across the body of the king and down the cane. Although his body grew weak and numb, his mind remained firm, for the survival of his subjects was his only concern.” 5

Lives as humans of every status: the humble accountant

The Buddha lived as countless human beings: men and women of different social statuses, nationality, professions, and race. This helps teach us, we should reject discrimination for any reason, without exception.

For instance, in one life he wa a humble “treasurer” — which is thematically about being “pious” — and at the same time is fully relatable (an accountant with a mother-in-law):

“The Bodhisattva lived as a king’s treasurer. He was renowned for his learning, nobility, and modest behavior. His lofty aspirations and complete honesty caused him to be revered above all others.

One day, the treasurer’s mother in law came and visited his home while he was away at the palace. She asked the treasurer’s wife if she was happy in their marriage and the wife responded that virtue such as her husbands would be hard to find even in the greatest mendicant who has renounced the world. The mother was hard of hearing and only heard the word “mendicant” and therefore misinterpreted her daughters words, thinking that she had said her husband was going to leave her and enter the forest to live as a mendicant. The mother started wailing in sadness, and seeing this, the daughter assumed her mother knew something she did not and in turn started to also believe that her husband was going to leave her. The rumor spread rapidly through the kingdom rapidly and before long, all the treasurer’s friends and family were overcome with grief, believing he was about to leave them all.

When the rumor finally reached the treasurer, he was confused but at the same time, he was honored that all these people viewed him as virtuous enough to live an ascetic life. He felt that after being held in such high regard, if he were to say it was just a rumor and continue to cling to the home life, he would not be worthy of their praise. Thus he decided to actually renounce the world and live in the woods as a mendicant and pursue nothing but meditation and cultivation of virtue.” [4]

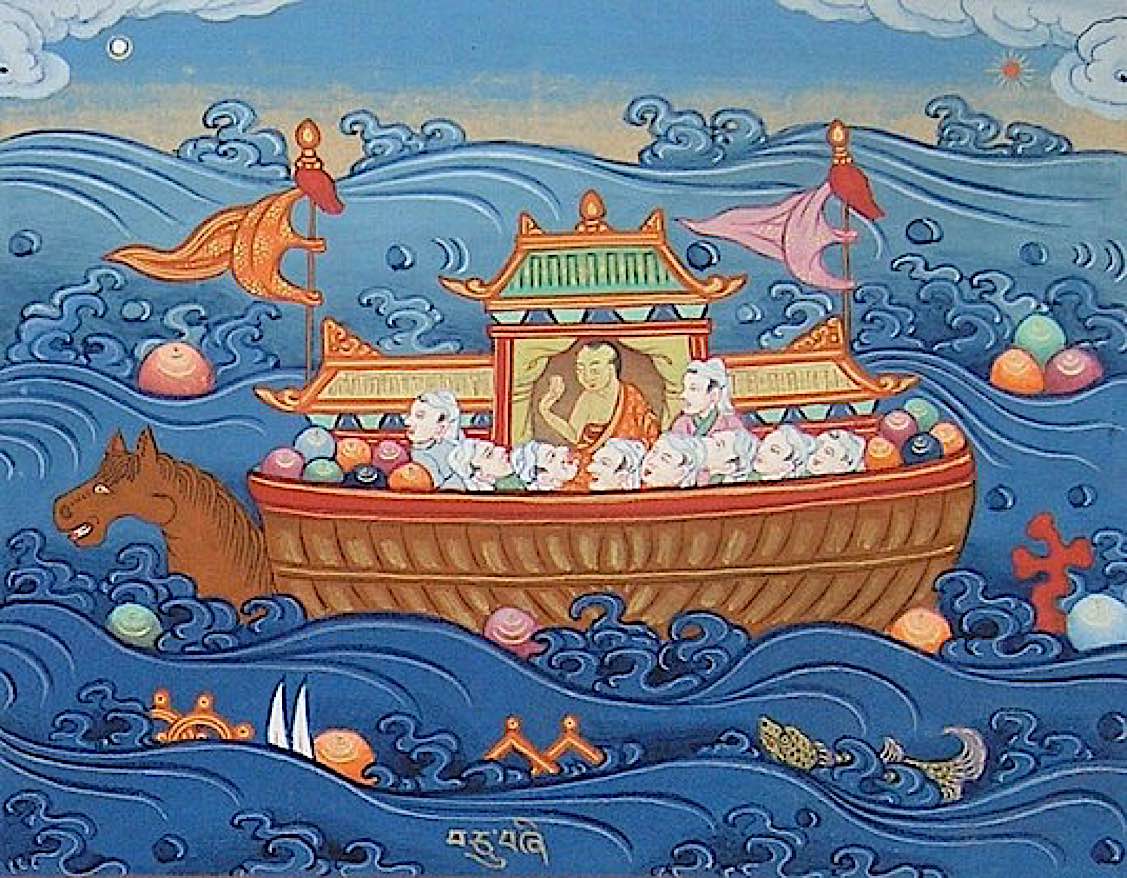

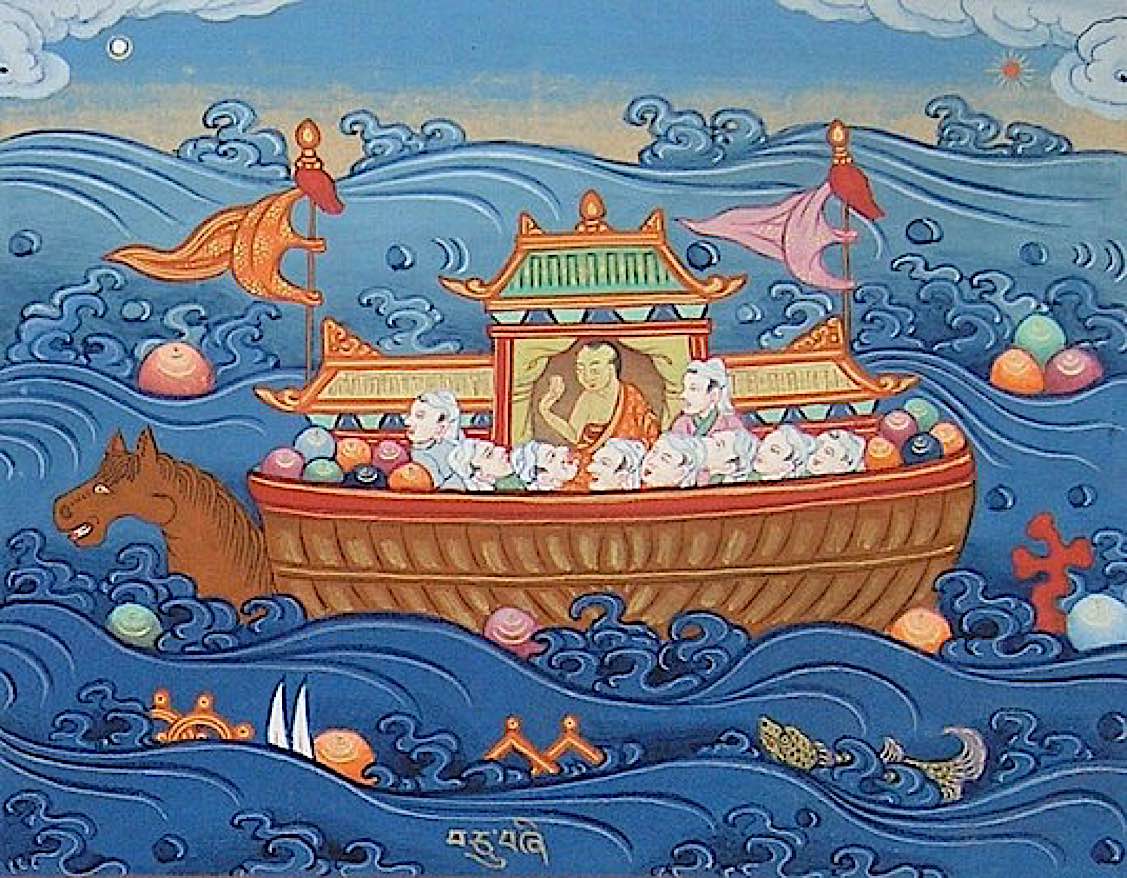

The ship’s captain and the storms

Suparaga, the Buddha’s previous life as a retiring ship’s captain, is a story of virtuous friends and the power of virtue:

“In one of his many lifetimes, the bodhisattva became a great ships captain. He had extensive knowledge of the constellations so he was never lost. He was known as Suparaga, meaning “Good Passage”.

Even as an old man in retirement, a group of merchants still wanted him to captain their vessel. Out of compassion he agreed, and as they set off they rejoiced, trusting that their journey would be successful. Yet on the first night, after they had lost sight of the shore and began to travel into a deeper part of the ocean inhabited by strange sea creatures, they ran into a terrible storm. They were not able to control the ship in the fierce winds.

No matter how much they struggled, they were unable to maintain their course. They were blown through many seas. They passed through the Sea of the Hoof Garlands, the Milk Ocean, the Sea of Fire Garlands, the Sea of Grass, and eventually the Sea of Reeds at the end of the world. Suparaga had been warning them to turn back the whole time but no matter how much they tried, the wind was too strong.

… The merchants began to cry and wail, begging various gods for aid as they continued on towards the deep abyss. At that point, Suparaga told the men to harness their courage and then bowed down, proclaiming to the men as well as the sky and ocean gods that he had never harmed a single being. He then asked the gods, by the power of his virtue, to turn the ship around and not let them fall into the Mare’s Mouth. So great was the power of his truth that the current and winds immediately changed direction. The sky began to clear.

The ship moved smoothly across the seas. The gods told the merchants to lower their nets at a certain location and when they pulled them back up they saw that they had been filled with treasure, silver, gold, sapphires, and beryl. They reached their destination safely.” [4]

Jatakas: beautiful, interesting, contemporary, and a full cycle of teachings

The Jataka tales are not only beautiful, interesting and historic pieces of literature but they remind us that the Buddha was once in our position, as someone or something stuck in the never-ending cycle of birth, death. Buddha’s own examples inspire us to carry on, in our own quest for enlightenment. The Jataka tales contain the gist of all the Buddhist teachings, in approachable story form.

Author Martin Rafe, who won a “Storytelling World Resource Award” for his “adult” version of the Jataka Tales, Endless Path explained it this way:

“The Four Noble Truths of Impermanence and the Way beyond its anguish — they’re here. The bodhisattva Vows, here. Advice on how to practice the Way. Here. The Eightfold Path. Here. The Four Abodes. Here. The six Realms. Here. The six paramitas and the four additiona ones, here, too. It’s all here, in lives lived, deeds done, choices made. Everything we need to keep going on the endless path.” 6

NOTES

[1]Sarah Shaw (trans) ‘The Jatakas: Birth Stories of the Boddhisatta’ (Penguin Books India, Haryana, India 2006.) P. XVIIII

[2]Shulamit Ambalu et al ‘The Religions Book’ (Dorling Kindersley Limited, London, UK 2013). P. 154

[4] Jatakamala: Garland of Stories https://www.himalayanart.org/pages/jataka.cfm

[5] The Monkey King https://www.himalayanart.org/items/50217

More articles by this author

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Lee Clarke | Contributing Author

Author | Buddha Weekly

“I’m a Buddhist, Quaker, Humanist, existentialist and pacifist. Budding professor of religion. Love many subjects, bilingual third year uni student.”