‘Outside Tradition and Scripture’ – Zen Buddhism: “If you meet the Buddha, kill him.”

Zen holds a special place in the heart and mind for many, perhaps because it is “seemingly” singular in its simplicity and elegance.

From single-pointed zazen mindfulness — facing a blank wall — to mysterious cyphers called Koans — “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” — Zen pursues the same Bodhisattva goal as other Mahayana Buddhists, with a distinctly focused method. That focus might be breath, art, caligraphy, archery, or riddles (koans) — but it’s all about focusing singularly.

By guest writer Lee Clarke

Zen is a style of Buddhism most commonly practised in and associated with Japan, although originating from India, then transmitted to China via the monk Bodhidharma as Ch’an. Although this article are my thoughts on the Zen Buddhist tradition from the perspective of a Western Buddhist who practices Zen, I try to cite sources for all of my points. I will focus on its unique methods; I don’t want to call them differences, because both its focus on single-pointed meditation and its emphasis on Buddha Nature are equally important to all Mahayana Buddhists. Let’s call them unique methods.

Shrouded in Mystery

Let’s face it — Zen is mysterious. Ask a Zen master to define Zen and he or she would likely say nothing. The point is made. Zen is about “figuring it out on your own” — although only after some instruction and foundation in the sutras. The Zen master might pose an “unsolvable riddle” or puzzling phrase — the famous Koans — or instruct you to face a blank wall and focus on your breath and nothing else — with an occasional whack with a stick to wake you up. Discipline plays a vital role in Zen.

Certainly, these are unique methods — at least the Koans and the stick are. Also unique is the simplicity of single-focus. You are unlikely to be taught five different methods; simplicity and clarity are important. After the basics — understanding the Four Noble Truths, the Eightfold Path, and so on — you will be guided to a single-focus method: most famously, zazen — “just sitting” — and koans. Basically, any disciplined means that can bring “insight.”

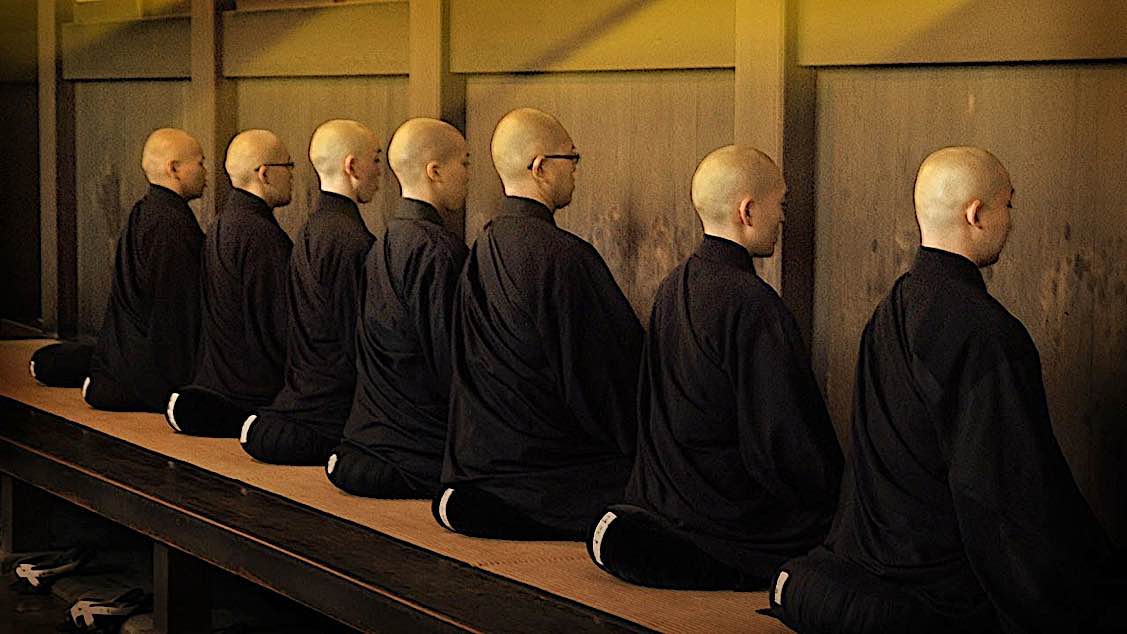

Part 1 of a documentary “Living in a Japanese Zen Monestary”:

Zen retreats are famous for their silence. There might be instruction, but practice is a solitary method (at least most of the time), and even meal times are a disciplined ritual. Discipline and ritual plays a role, but mostly in the sense of simplifying and codifying actions. Mystery is a good, general description of Zen.

Still, Zen isn’t about only one method. Different Zen schools practice different methods: single-pointed ritual concentration (chanting, sutra recitation) — but with single-pointed concentration; single-pointed archery or martial arts — again with acute mind-focus; zen gardening, cooking, art, caligraphy. What unites all the diverse techniques is extreme simplicity, single-pointed focus, mind-training, and — ultimately — satori-like moments: glimpses of reality just as it is. (Even skateboarding can be a Zen technique. See our early feature on the Zen of Skateboarding>>)

Origins of Zen

Zen formally organized in China where it is known as Ch’an Buddhism, although it was brought to the Chinese by the famous Indian monk, Bodhidharma who defined the word “Zen” as

“A direct transmission of awakened consciousness, outside tradition and outside scriptures”. [1]

Bodhidharma’s definition sums up the Zen perspective perfectly. Zen, like all other schools of Buddhism seeks the attainment of enlightenment and liberation from the cycle of birth, death and rebirth. It also though, seeks the recognition that each individual is a potential Buddha, recognizing our ineherent Buddha nature common to all sentient beings. Like other Mahayana schools, it is a primary doctrine in Zen.

Buddha Nature

Hakuin Ekaku, one of the most important Japanese Zen masters defined Buddha Nature:

All beings by nature are Buddhas,

as ice by nature is water.

Apart from water there is no ice;

apart from beings, no Buddhas.

Here’s where the similarity to other Mahayana schools is singular. Zen bases its foundation in Buddha’s teachings and sturas, but emphasizes that we cannot gain enlightenment solely by studying scriptures and reciting mantras alone — not even by examining teachings logically and rationally. Though this may seem bizarre to our cultural mindset, Zen teaches that we have to do his through our own direct action with only ourselves as a guide. Other schools also teach method and self-realization, but Zen is emphatic on this point. As the BBC article on Zen Buddhism states on the tradition:

Human beings can’t learn this truth by philosophising or rational thought, nor by studying scriptures, taking part in worship rites and rituals or many of the other things that people think religious people do. The first step is to control our minds through meditation…to give up logical thinking and avoid getting trapped in a spider’s web of words.[1]

Skilful means and no Sutras?

This may seem strange to Buddhists and non-Buddhists who are not Zen practitioners: how can one ignore the Buddhist scriptures (Sutras) which contain the word and teaching of the Buddha or recite mantras and sutras — and only pursue self-insight? Of course, Zen doesn’t ignore Sutra; it fulfils them. In those very Sutras, Buddha teaches “right meditation” which includes focus on breath, mindfulness and other insightful techniques — so it’s simply not the case that Zen ignores Sutra. But, Buddha taught many methods, customizing methods to the students he encountered, and one of these methods was the Ch’an / Zen approach:

“When Buddha was in Grdhrakuta mountain he turned a flower in his fingers and held it before his listeners. Everyone was silent, only Maha-Kashapa smiled at this revelation, although he tried to control the lines of his face”.[2]

Buddha demonstrated the direct insight that is the main Zen “focus”. In other words, Zen derives from Buddha as one of his many “skilful means.”

Enlightenment requires self-insight

All Buddhists paths — including Tantrics and Theravadin — teach methods for self-insight, ultimately leaving to the goal of Enlightenment. Buddha Himself sat under the Bodhi tree and went deep into his own mind to achieve Enlightenment. In this, Zen is not unique. It is unique mostly in emphasis and method.

In the Dhammapada, Buddha teaches that we must reach nirvana ourselves and we must do so alone, no one can complete the process for them:

“All the effort must be made by you; Buddhas only show the way. Follow this path and practice meditation. Go beyond the power of Mara.”[3]

This does not mean that we are being selfish. The Mahayana goal is to attain Enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings. But, the Buddha’s teaching clearly emphasizes the Zen position of ultimately going “outside scriptures” To use a school metaphor, Sutras are the metaphorical “course textbook”— and our professor is our guide — but, we still have to study, learn and develop insight on our own.

Koans are entirely unique

A singularly unique feature of the Zen tradition is the use of what looks like strange and illogical riddles — known as Koans. These are more associated with the Rinzi school of Zen but find their place in other schools too, especially in the modern age where traditions tend to mix. Trying to examine them with reason and logic will not lead you anywhere — which is the point, in a way. Rather, you have to let go of all pre-conceived notions in order to understand what the Koans are saying.

One of the most famous and striking Zen Koans is as follows:

“If you meet the Buddha, kill him.”

If this is taken literally, this koan, attributed to Zen master Linji Yixuan, can seem incredibly shocking. That is also the point. Shock and confusion and puzzles are used to “shake up our rational mind” and inspire the creative, conceptual mind.

Killing the Buddha?

What does it mean, this crazy riddle that seems to tell us to kill the very person who founded Buddhism?

Of course, you are not supposed to interpret this literally. As Barbara O’Brien says “

In Zen, it’s generally understood that “When you meet the Buddha, kill him” refers to “killing” a Buddha you perceive as separate from yourself because such a Buddha is an illusion.”[4]

When taken in this context, it can be seen clearly that the Koan is talking about Buddha Nature and can be seen as incredibly profound and even liberating when its true meaning is realised.

Other interpretations include “No matter what you think you understand about Buddha’s teachings, chances are you are wrong.”

One hand clapping? Exploring non-duality

Another famous one is ‘What is the sound of one hand clapping?’

The story goes that a young boy Toyo finally managed to persuade the Zen master Mokurai, to give him a teaching. Mokurai said to Toyo

“You can hear the sound of two hands when they clap together. Now show me the sound of one hand.”

Toyo returned to his room to try and consider the problem and he returned to Mokurai with many suggestions of what the sound could be, from Geisha music, dripping water and the sound of an owl. It is then written “at last little Toyo entered true mediation and transcended all sounds. ‘I could collect no more’, he explained later ‘so I reached the soundless sound’ – Toyo had realised the sound of one hand.[5]

To find the sound of one hand, Toyo had to rise above normal rationalisation because as we saw, this didn’t bring the answer. It’s only when he ‘let himself go’ in meditation that he finally found the answer.

According to Victor Hogen (Zen Sand: The Book of Capping Phrases for Koan Practice),

Koan after koan explores the theme of nonduality. Hakuin’s well-known koan, “Two hands clap and there is a sound, what is the sound of one hand?” is clearly about two and one. The koan asks, you know what duality is, now what is nonduality? In “What is your original face before your mother and father were born?” the phrase “father and mother” alludes to duality. This is obvious to someone versed in the Chinese tradition, where so much philosophical thought is presented in the imagery of paired opposites. The phrase “your original face” alludes to the original nonduality.

Lightbulb moments

One of my favourite things about reading Koans is the little ‘lightbulb moment’ that you get in your mind when you finally gain some insight. One of the main schools of Zen, Rinzai teaches that you can gain realizations instantly, for a very brief period, known as Satori – it isn’t true and final enlightenment but a brief look at what it’s like. As a Zen website states, Koans are made to “trigger enlightenment” and “designed to force and shock the mind into awareness.” Satori are the big lightbulb moments?[6]

Mindfulness through activities

Zen Buddhism though didn’t stay confined monasteries; it had a massive impact on Japanese culture and society – on lay people in everyday life and activities as much as it did on monastic culture. As Ninian Smart describes:

“It wove together meditation and the martial arts, archery and swordplay could be developed in a Zen way…feminine arts such as flower arrangement and tea-making were also given a Zen mode and flavour. Zen ideals – sparseness, cleanness, control and spontaneity – came to be influential in all the main arts, such as painting, arranging gardens and calligraphy.”[7]

Buddhism in general as well as the Zen mindset also had a massive impact on the famous Samurai warrior caste of Japan and Zen Buddhism, along with Confucianism and the Indigenous Japanese Shinto religion all informed the Samurai Bushido ethos. As Ben Hubbard says:

“Buddhism taught a warrior not to fear death, as he would be reincarnated in the next life. Zen helped a warrior to ‘empty his mind’ and maintain clarity in battle’.[8]

Haikus

Zen Buddhism had a major cultural impact on Japan. As part of this, it also had a big impact on Japanese literature which can particularly be seen in the form of some Haiku. Haikus are a form of Japanese poetry, now known around the globe for their brevity (traditionally composed of three lines of 5, 7 and then 5 syllables) and their ability to intensely capture a single moment in verse. While they are not specifically ‘Buddhist poetry’ or even ‘Zen poetry’, many of the most famous Haiku masters were Buddhists and many of the poems, which are in many cases about the beauty of nature do have a ‘Zen feel’ and many are about Zen outright.

Matsuo Basho – considered the supreme Haiku master of Japan was a wandering Zen Buddhist, references the Buddha in many of his Haiku and inserts his Zen mindset into many more. For example

“Not one traveller

braves this road

Autumn night”[9]

Another Buddhist Haiku was a death poem – normally the last statement of a poet – by Gozan just before he died at the age of 71.

“The snow of yesterday

That fell like cherry blossoms

Is water once again”[10]

In my opinion, this represents the cycle of Samsara, an opinion also shared by John Asano but as it says, the snow turned to water and melted (death) and then when it’s cold, the water will eventually become snow once again – a perfect representation of rebirth!

Zen in the West

Zen Buddhism has had a major impact in the west. Many zen-like phrases have become “sayings” and the word “zen” has taken on a meaning somewhat akin to “mystery”: “I’m Being Zen” or “That’s really Zen”

Zen is popular in the West due to its simple but profound spiritual methods; they seem less “restrictive” than more rigid religions in the eyes of many. Like other forms of Buddhism, it doesn’t require a belief in a God or a higher power.

Profound Method

I think Zen is a profound method — that ultimately could lead to profound truth. Sometimes sitting down to meditate and taking a deep breath is all that we need to reveal the essence of the Buddhist path.

This is illustrated in a last Koan that I will share. A university professor wanted to learn about Zen from the Japanese Zen master Nan-In. (A scene that has been copied in movies.) The master served tea and kept on pouring until it was overflowing from the cup:

“The professor watched the overflow until he could no longer restrain himself: ‘It is overfull, no more will go in!’

‘Like this cup’ Nan-In said ‘You are full of your own opinions and speculations. How can I show you Zen unless you first empty your cup?’

As Buddhists, we must remember from time to time, no matter what tradition we follow to “empty our cups”.[11]

NOTES

[1]BBC ‘Zen Buddhism’ at https://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/buddhism/subdivisions/zen_1.shtml [Accessed 22nd June 2018]

[2]Paul Reps (editor) ‘Zen Flesh, Zen Bones: A collection of Zen and Pre-Zen Writings’ (Penguin Books: England, 1971) P.100

[3]Eknath Easwaran (trans) ‘The Dhammapada’ (Nilgiri Press: California,United States, 2008) P.205

[4]Barbara O’Brien ‘Kill the Buddha? A closer look at a confusing Koan’ at https://www.thoughtco.com/kill-the-buddha-449940 [Accessed 22nd June 2018]

[5]Paul Reps (editor) ‘Zen Flesh, Zen Bones: A collection of Zen and Pre-Zen Writings’ (Penguin Books: England, 1971) P.p. 34-35

[6]Zen Buddhism ‘Rinzai Zen (Rinzai-Shu) at https://www.zen-buddhism.net/two-schools-of-zen/rinzai-zen.html {Accessed 22nd June 2018]

[7]Ninian Smart ‘The World’s Religions’ (Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge: Victoria, Australia 1989). P.145

[8]Ben Hubbard ‘The Golden Age of The Samurai’ (Amber Books: London, UK 2017) P.137

[9]Basho ‘On Love and Barley’ – Haiku of Basho’ (The Penguin Group: London, UK, 1985). P.56

[10]John Asano ‘12 Haiku that reflect on Zen Buddhism’ at https://theculturetrip.com/asia/japan/articles/12-haiku-that-reflect-on-zen-buddhism/ [Accessed 22nd June 2018]

[11]Paul Reps (editor) ‘Zen Flesh, Zen Bones: A collection of Zen and Pre-Zen Writings’ (Penguin Books: England, 1971). P.17

More articles by this author

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Lee Clarke | Contributing Author

Author | Buddha Weekly

“I’m a Buddhist, Quaker, Humanist, existentialist and pacifist. Budding professor of religion. Love many subjects, bilingual third year uni student.”