Upaya: Is Skillful Means, Imagination and Creativity the Path to Realizations? Experiential Buddhist Practice or Yogas Enhance Intellectual Study.

Buddha taught with “upaya” which means “skillful means” using that most powerful of mechanisms of consciousness, the “imagination.” Skillful means is not a fiction, but rather a way of comprehending truth through illustrations, imagination and imagery. This is why both Buddha and Jesus taught in parables — bridging imagination with intellect. The ability to use “story” to convey truth is as old as the most ancient of myths. It is also why creativity is vital to Buddhist practice.

Throughout history, mankind’s great philosophers, scientists, religious thinkers, artists — and Buddhist Yogis — tended to be those with active imaginations and the ability to visualize creatively. Da Vinci was both an inventor and an artist. Inventors are, by definition creators. Scientists may be rational, but breakthroughs come from going beyond what we know already and asking “what if…” It is no different in spiritual practices.

Proving the power of imagination — watch a movie, read a book?

The great Buddhist teacher Gelek Rimpoche once described the best method to prove the benefits of visualization is watching a gripping movie— or reading an intense novel. When we watch a “horror movie” and feel a visceral, too real fear arise, our knuckles clench, we clench our teeth, and sometimes we yell out loud “don’t go in there!” to the imaginary protagonist about to be “eaten” by the monster.

How does that work? Our mind temporarily suspends disbelief. This doesn’t work if the first scene of the movie is the monster eating a victim. The writer has to “build up” a credible world, and work on creating emotions and suspense so that we are “invested” in the character.

Let’s face it — we know the monster in the movie or novel is not real. It’s makeup and FX or words. So, why do we actually feel tangible fear — or other emotions in the case of, for example, a romance story, a stirring adventure or a tragic biography? It starts with “investing” in the journey.

In the case of the spiritual journey, this is an even bigger challenge than the one faced by the novelist or scriptwriter. Basically, we take a journey in our own mind and imagination. And, what is mind, exactly? It’s easier to explain what mind “is not” than what it is. Khenpo Karthar Rinpoche explained:

“You cannot say the mind is something; you cannot say the mind is nothing; you cannot say it is substantial; you cannot say it is nonexistent and utterly insubstantial. Its nature cannot be described by anyone.” [3]

Buddha, Jesus, Lao Tzu — the visionaries

Some may dismiss this concept of imagination as a vehicle as “too New Age,” but we only have to consider our great spiritual leaders, from Buddha to Jesus to Lao Tzu, who retreated into the depths of their minds to find revelations to dismiss this claim. Buddha battled “Mara” under the Bodhi tree; Jesus famously faced temptation alone in the desert. Lao Tzu, the founder of Taoism (Daoism), likewise crossed a desert, in his case on a water buffalo, leaving behind the corruption of the world on a heroic quest for truth.

Most of the great Buddhist Yogis — from Atisha in India to Milarepa in Tibet — the great visionaries of the Vajrayana tradition of Buddhism, faced not only gruelling, isolated visionary experiences, they ultimately encountered their Buddha or Yidam or inspiration through hardships and inner retreat. Likewise, for the great Catholic saints — visionaries who experienced visions, rather than relied on towering intellects. Of course, there is a fine line between visionary and “madness” — which is why we still need the teaching and guidance of a spiritual guide, guru, or teacher.

Does deeper understanding arise from imagination?

Self-experiencing retreats and meditations are critical aspects of most spiritual paths — and certainly in Vajrayana Buddhism. This is why in Buddhism we call our meditations “practice” rather than “study.” Even reciting sutra is a “practice” — we recite out loud and try to envision what is happening, rather than simply “learn it.”

Imagination allows us to see beyond the limits of our limited knowledge, and can help us to reach a deeper understanding of what is real and true. By using visualization techniques in meditation and retreat, we can unlock hidden truths within ourselves that are otherwise inaccessible. So while Buddhism may espouse rationality and logic as its methods of inquiry, it is imagination — through visualization and creativity — that ultimately leads us down the path to Enlightenment.

While such imaginative visualization may seem esoteric or out of the ordinary, it is actually a form of Buddhism that has been practiced for centuries. By engaging in deep contemplation and visualizing our deepest truths and desires, we can tap into a source of wisdom and enlightenment that transcends study alone. So while many religions focus on dogma and strict adherence to rules, Buddhism encourages us to be creative and let our imaginations guide us to the truth.

Waking up — stirring the mind to see beyond

In Buddhism, Enlightenment is often translated as “to awake” or “waking up.” In Zen or Chan Buddhism we try to shake up our minds to see beyond our conditioning, with Koans (unsolvable riddles) and long sessions of Zazen. In Vajrayana Buddhism — which seems “strange” or irrational to some Buddhists — we try to shake up our perceptions; we try to recognize “the true nature of reality” and embrace the emptiness of illusory ego. In the elder schools and Pali Suttas, we are taught methods and meritorious conduct — learning from the visionary experiences of Shakyamuni Buddha.

Khenpo Karthar Rinpoche, explained, “The nature of the mind of all sentient beings, irrespective of any obscurations that may obscure or conceal it, has from the very beginning been buddha. There is an inherent wakefulness and perfection to the mind of each and every being.” [3]

What motivates us to try to “wake up” and see the nature of the ultimate truth? Herbie Hancock, the great jazz musician (who was famously a Buddhist) described the motivation this way: “fear, pain and suffering” but also, as he pointed out “joy, desire, humor and observation.” [2] Hancock actually went so far as to claim Buddhism specifically “expands our creativity.”

Suffering teaches us to “directly experience”

Buddhism views suffering as the root of all our troubles — and Buddhism’s focus is on overcoming suffering and attachments.

Can Buddhism be considered “rational”? Yes, Buddhism does embrace rationality and logic as a means to an end — which is why meditation and retreats are important aspects of Buddhism. But Buddhism is not simply about understanding or intellectual inquiry; it involves a direct experience of the truth that surpasses mere rational thoughts or deduction. And that experience often comes through using the power of imagination — using visualization techniques to unlock hidden truths within ourselves, and letting our imaginations guide us towards Enlightenment.

So while some may argue that Buddhism relies too heavily on intuition or creativity, there is no doubt that it also embraces rationality and logic as tools for understanding the truth. While visionary Buddhism (i.e. Vajrayana) may seem “strange” or “esoteric,” it is this combination of reason and imagination that ultimately leads us toward our ultimate goal: a deeper understanding of ourselves and the world around us, free from suffering and pain.

Buddhism embraces the “Emptiness” and discard preconceptions

Some scholars incorrectly associate Buddha’s teaching on Emptiness (Shunyata) with negativity and nihilism — when, in fact, Buddhism embraces Emptiness as a vehicle of creative inspiration. By removing the artificial, psychological construct of ego — that binds us to our notions with attachments and perceptions — Shunyata, or Emptiness embraces the totality of concept, creativity, and “the possible.”

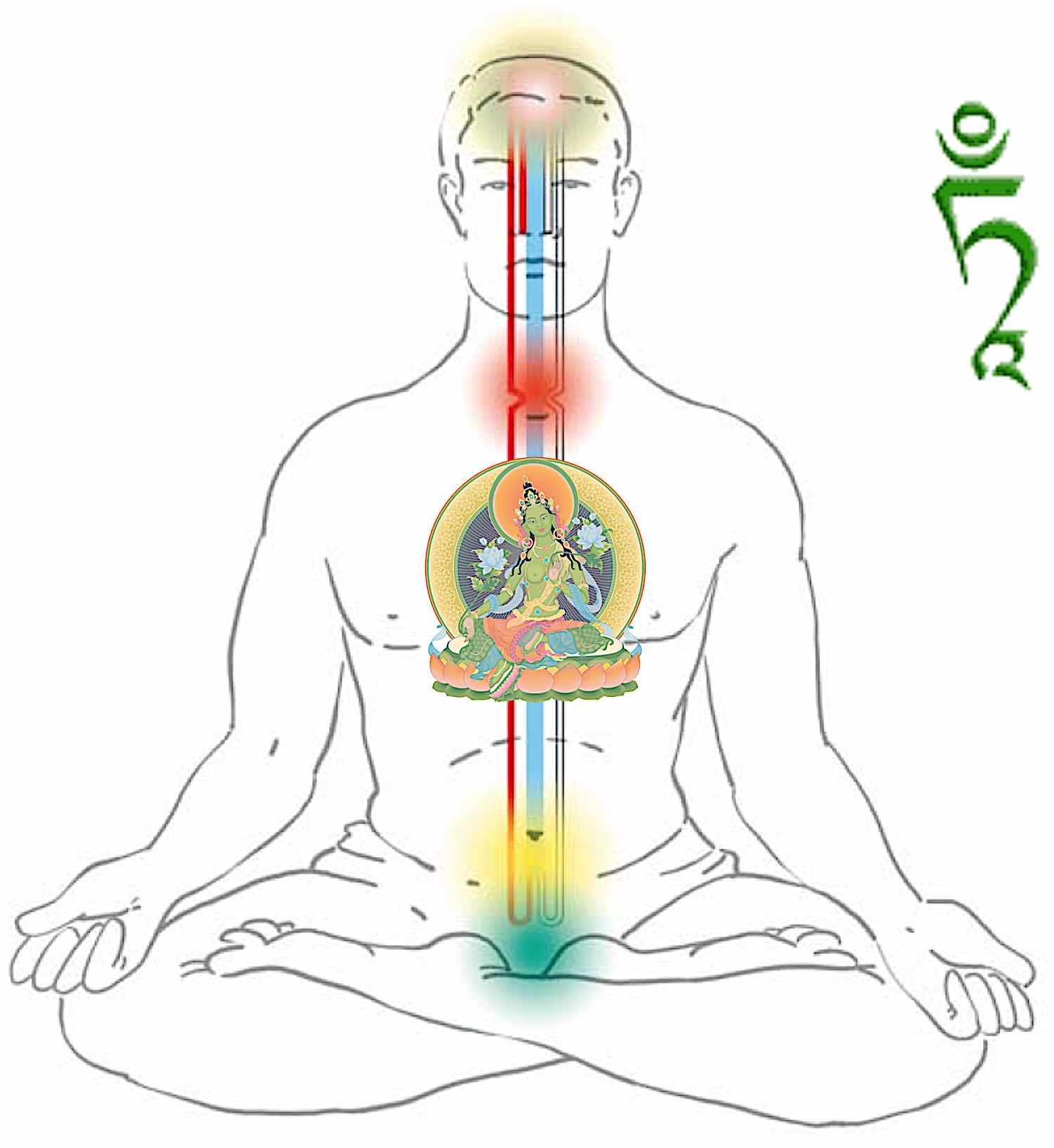

In Vajrayana deity practices, for example, at all levels of practice, we first “dissolve” ourselves into emptiness, then recreate our “non-self” as an idealized icon of Enlightenment — a deity such as compassionate Avalokiteshvara. We then dissolve this once again. Why go to these elaborate lengths to visualize the deconstruction of our artificial selves? To “show” the mind that we are not just our fragile egos and to demonstrate that we are something much greater — none other than potential Buddhas ourselves. Rather than “nihilistic” or depressing, it is inspiring, although it tends to be me the most uplifting for those who tend to have creative minds.

Creativity is a “vehicle of experience” in Vajrayana practice

Whether the Vajrayana teacher advises us to “visualize” a deity with 1000 arms to symbolize the endless compassion of the Bodhisattva — or uses the language “imagine” — there is no doubt that these skillful means are vital as a method. It’s not about making practices “exotic” or alluring. While sutra study and commentaries are vital as foundations, ultimately we have to experience them for ourselves.

Gelek Rimpoche explained (a full nutshell explanation!):

“We have five skandhas, or the five aggregates [form, sensation, perception, mental formations, consciousness]. The essence of the Vajrayana is to transform these five aggregates into five wisdoms through visualizations and other techniques. We play with our emotions and work with them. It is a very quick path. In the Theravadin tradition, the goal is the arhant level, total freedom from pain, sufferings, and delusions. The goal in the Mahayana tradition is the buddha state, or buddhahood, which is the one state beyond the arhant level—but it takes aeons to reach. And in the Vajrayana, the goal is Buddhahood, which is considered reachable within your lifetime, whatever short amount of life you have left.” [4]

What is the “vehicle of experience?” Inevitably, it is a visionary journey. Consider Buddha sitting under the Bodhi tree ready to wrestle Mara in his own mind. Did Mara manifest his armies around Buddha, assailing him with arrows in our discernable reality — or was it a visionary journey in Shakyamuni’s vast mindscape? It doesn’t matter, in Buddhist terms, since our perceptions are illusory or misunderstood.

One easy way to “step in” to visualization of a deity as a practice is to follow a guided meditation of an experienced teacher. Here is an example, of a short Green Tara guided visualization teaching (in this case Green Tara):

Rely on imagination, but trust in the Three Jewels

What separates the visionary meditation of a Buddhist from a romp through the mind and imagination or a New Age trend? While imagination and visualization may be the vehicle, Buddhists have a destination and a Refuge. The destination is Enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings — the Bodhichitta mission — while the Refuge that we rely on are the Three Jewels: Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. The visionary paths, and notably Vajrayana, rely on the guidance of a Guru — who represents the refuge as the teacher, teachings and supporting friend. Blind imagination without the guide is simply a wild ride or a dream. Imagination and visions, in Buddhism, are in service of the mission — no more than a tool.

So, while imagination may be the “fast path” secret to accomplishing the Bodhichitta mission — it remains in service to the compassionate Dharma mission.

Buddhism encourages us to use our own creative imagination — for it is that same imagination that can open the doors of perception, and lead us to Enlightenment. Yet, it is not unguided, unbridled, whimsical fantasy, even when we visualize 1000-armed Bodhisattvas or enlightened beings who manifest as mythical images.

Buddhism encourages you to tap into your power of imagination. Let your creativity drive you on the journey toward truth, and unlock the wisdom and compassion that lies at the heart of all beings.

What about those who cannot visualize?

Everyone can visualize. If you couldn’t visualize, you wouldn’t be able to enjoy a movie or a novel. Usually it’s just our own obstacles that “block” our apparent ability to visualize.

Alexander Berzin, in an excellent feature on “How to visualize,” explains it this way:

“Many people say, “Well, I can’t visualize. So how can I use these methods?” Actually, if we take a moment to investigate, we find that we all do have powers of imagination. For instance, try to remember what your mother or your best friend, it doesn’t matter who, looks like. Please do that for a moment. Almost all of us are capable of remembering what our most closely loved ones look like. So, almost all of us are able to visualize.” [5]

Likewise, if we say a name or label out loud — such as “Tara” or “Buddha” — we almost always get a flash of an image of that labelled person or being in our heads. If you think of a “red apple” you know what that looks like instinctively. Therefore, you can visualize.

There are, psychologically speaking, two sides of the human brain. There is the so-called rational mind and intuitive mind. Or the right brain, left brain. Vajrayana and other forms of visual meditation simply recognize that both are important. By generating imaginative images, our mind responds to the symbolism of those images.

What about Aphantasia — the inability to “picture”

There is a term for people who legitimately cannot imagine or visualize. Aphantasia — which we covered in this extensive feature (here) — is certainly a phenomenon, but it’s extremely rare. In most cases, we all visualize, but some people find it difficult to do “on demand” — such as when a teacher says, “now visualize healing light going out to all beings in the world.” We think we don’t “see” that image — but actually, the moment the teacher speaks those words, that image flashes across your neural network. Sustained visualization is more difficult, and requires discipline, which is why in Buddhism, we call our meditations “practice.”

Dr. Bezin explained:

“In order to understand the various levels and usages of visualization, first we need to throw the word visualization out of the window. It is the wrong word because the word visualization implies something visual. In other words, it implies working with visual images and it also implies working with our eyes. This is incorrect. Instead, we are working with the imagination. When we work with the imagination we’re not only working with imagined sights, but also with imagined sounds, smells, physical sensations, feelings – emotional feelings – and so on.” [5]

- In part 2 of this series, we explore: How to Visualize or Imagine in Vajrayana, step-by-step.

Notes

[1] Madhyantavibhaga

[2] In Norton Lecture, Hancock Discusses Buddhism, Sources of Creativity, feature by Joanie Timmins, in The Harvard Crimson.

[3] Vajrayana Explained by Khenpo Karthar Rinpoche, feature in Lion’s Roar Oct 21, 2019.

[4] A Lama for all seasons, Trycicle magazine interview with Gelek Rimpoche

More articles by this author

Guru Rinpoche is ready to answer and grant wishes: “Repeat this prayer continuously” for the granting of wishes

VIDEO: Vajrapani Vajra Armor Mantra: Supreme Protection of Dorje Godrab Vajrakavaca from Padmasambhava

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Lee Kane

Author | Buddha Weekly

Lee Kane is the editor of Buddha Weekly, since 2007. His main focuses as a writer are mindfulness techniques, meditation, Dharma and Sutra commentaries, Buddhist practices, international perspectives and traditions, Vajrayana, Mahayana, Zen. He also covers various events.

Lee also contributes as a writer to various other online magazines and blogs.