A Picture is NOT worth 1000 Words — the Buddha Dharma is a Tradition of Words — A Guide for Those Who Can’t Visualize (Aphantasia)

“A picture is NOT worth 1000 words” when it comes to Buddhism. Buddhism is an oral tradition, handed down by lineage to written sutras and written tantras. The words transcend any images that might arise from their messages. [For visual examples, see the section below: Examples in Sadhanas vs Thangkas.]

When we become Buddhists, we take Refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. Dharma (in this context) is the teachings, which are always conveyed in words. Not pictures. While we may, as a practice, out of respect, bow to a statue of Buddha or a thangka of Tara, we are actually prostrating to the Dharma — the living teachings. When we are in trouble, when there is a natural disaster, when we need help with obstacles to our practice — the go-to first instruction from our teachers is normally to recite sutras or mantras. Dharma Words.

Visualizing is a bonus, but for those of us unable to properly visualize, we need not despair. In Buddhism, Dharma and the words are profoundly powerful. It is through words the tradition continues. It is through words we pass along the teachings. It is through words we practice. Visualization is helpful — simply saying or reading the words tends to evoke “pictures” for most of us — but practice without the ability to Visualize is no less potent.

At the recent Green Tara puja in Taiwan, Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche said, “We tend to make people think [that to practice] you need to sit, chant, meditate, not eat this and that, be a monk, all these restrictions—and this is totally wrong. We always say there are 84000 methods, but then when we implement it, we always implement just one.” [3] There is no need to despair if we are unable to practice in one particular way — for example, an inability to visualize, known as Aphantasia [1] — we have 83,999 other ways to practice. One of these, of course, is to simply practice in front of a beautiful Thankha of what you are trying to visualize.

The one method, however, which is indispensable, is language. The Word, spoken or written, is how Dharma is transmitted. We can practice without the ability to visualize, or without the luxury of making offerings — for example if we are unable to afford offerings — or, without the benefit of a simple shrine (some of us live in closet-sized apartments), or without the support of a nice printed Thangka image, but we CANNOT practice without words: in thoughts, written words and spoken language.

[Interestingly, the 84,000 project is a worthy project that has committed to translating the 84,000 texts of the Tibetan Buddhist Canon, freely published as Words on their website here>>]

The Profound Word — Words of Wisdom

When we say the word “Buddha” — for most of us — it conjures a feeling of kindness, peace, contentment, wisdom, the Enlightened Mind. The word “Buddha” has this power. More so than a picture or statue of the Buddha — which are widely open to artistic interpretation.

When we say the word “Guan Yin” or “Avalokiteshvara” or “Chenrezig” it invokes immediately the concept of compassion and kindness — regardless of our ability to visualize. We don’t have to see an image of the thousand-armed Chenrezig to know what they stand for — and thousand hands reaching out to save and help us. Again, the word is more evocative than any picture could be.

If we speak the word “Tara” instantly we feel safe. Her name summons this feeling without being able to see her face in our mind. That image doesn’t have to be visualized. Just saying the word Tara! is a practice. Khenpo Sodargye gave several examples in his amazing lecture series on Tara, including the story of someone who only had time to call out “Tara!”[2] — and was immediately rescued. The word is profound. It triggers the image in our heads — not the other way around. It starts with the word.

The name Hayagriva — Avalokiteshvara’s wrathful manifestation — might instantly provoke a more adrenalin response — similar to being in the presence of a heroic warrior. We feel safe and strong. We do not need to be able to visualize his three wrathful faces and six mighty arms. While images are helpful symbols, and trigger mental resonance in meditation, they are not required to practice even complex meditation sadhanas. It is for this reason, most of the Buddhist practice sadhanas are rich with descriptive words. In absence of our ability to visualize, we can paint a picture of words.

Of course, as Dr. Alexander Berzin explained: “one of the things that characterize the Tibetan form of Buddhism is its extensive use of visualization, much more than in any other form of Buddhism.”[4] This has a number or purposes, among them, helping us overcome our incorrect perceptions of “reality” — however, it is incorrect to assume you cannot practice Tibetan Buddhism if you have no visual imagination.

Dr. Berzin continues: “In order to understand the various levels and usages of visualization, first we need to throw the word visualization out of the window. It is the wrong word because the word visualization implies something visual. In other words, it implies working with visual images and it also implies working with our eyes. This is incorrect. Instead, we are working with the imagination. When we work with the imagination we’re not only working with imagined sights, but also with imagined sounds, smells, physical sensations, feelings – emotional feelings – and so on.”

Buddhism is a Tradition of Words

Quotes from Sutra (Sutta) are timeless and memorable. The same cannot be said of even the most masterful of Buddhist paintings. After all, the words are the words of the Buddha, while any art you might see, or anything you might imagine, is interpreted with liberties.

Consider these authentic snippet quotes from Sutta (among hundreds of thousands of potential sound bites);

“By not harming living beings, one is called noble” Dhammapada 270

“By relying upon me as a good friend… beings are freed from sorrow, lamentation, pain, displeasure and despair.” — Upaḍḍhasutta

“You yourself must strive. The Buddhas only point the way” — Dhammapada

“A true friend is one who stands by you in need.” — Sigalovada Sutta

“All experiences are preceded by mind, having mind as their master, created by mind.” — Dhammapada

“Give even if you only have a little.” Dhammapada 224

“Develop and cultivate the liberation of mind by lovingkindness, make it our vehicle, make it our basis, stabilize it, exercise ourselves in it, and fully perfect it.” — Samyutta Nikaya (page 708, Bhikku Bodhi’s translation.

“Some do not understand that we must die, but those who do realize this settle their quarrels” — Dhammapada

“Should a person do good, let him do it again and again. Let him find pleasure therein, for blissful is the accumulation of good.” Dhammapada 118

“Whoever doesn’t flare up at someone who’s angry wins a battle hard to win.” Samyutta Nikaya

“Radiate boundless love towards the entire world.” Buddha in Karaniya Metta Sutta

“If a man going down into a river, swollen and swiftly flowing, is carred away by the current — how can he help others across?” The Buddha, from Sutta Nipata

Why do I think this is worth writing about? (Pun intended since we’re talking about words.) Because many Buddhists struggle with visualizing in their meditation. For example: “Visualize white, healing light coming your heart and going out to all beings in the Universe” as a guided meditation in words is profound and beautiful — but it’s almost impossible to visualize white light going out to countless beings. (White light, maybe, but trillions of beings?)

In other words (pun intended again!) — don’t sweat it if you can’t visualize in meditation.

You are in no way prevented from practicing any form of meditative yogas, including the Highest Yoga Tantras. The great teachers took care of those of us who can’t visualize — a condition known as Aphantasia — by writing elaborate sadhanas with every detail of the visualization. Simply say the words, and trust in the power of words.

The power of words transcends images

Sadhanas might instruct us to “imagine we are Buddha” but it is not really left to our imagination. The level of detail in even a simple sadhana is so vast, that reading the words is the only viable practice. We may catch glimpses of the Buddha as we say these words, with our minds in a receptive state — but this is more the power of words, rather than images.

Sutras and tantras, after all, are oral traditions (words) later written — not illustrated.

Likewise, when we chant Buddhist mantras, such as “Om Mani Padme Hum,” we feel the compassion and kindness. When we say “Om Tare Tuttare Ture Svaha” we feel instantly protected. When a loved one passes away, we find comfort in “Om Amitabha Hri”, which makes us think instantly of Amitabha’s pureland. This is the power of sound and words on the mind.

It is not necessary, even in Highest Yoga Tantra Vajrayana, to be able to vividly visualize. In fact, many of the most profound practitioners have limited or no ability to visualize. It is for this reason, that Buddhist Sadhanas are so eloquent, poetic, and descriptive. Even for those who cannot visualize or imagine in their mind — they have a word picture that has every bit as profound as any dream-like visions.

Of course, Vajrayana does place some emphasis on visualizing, but as Dudjom Rinpoche used to say it does not matter if you cannot visualize; what is more important is to feel the presence in your heart, and to know that this presence embodies the blessings, compassion, energy, and wisdom of all the Buddhas.

Overcoming Illusory Perceptions

While it is true that Vajrayana is partly about “overcoming the illusory perceptions” — what we think of as mundane reality — this can be done equally well by the poet and the speaker as the dreamer.

In fact, training ourselves to imagine vividly can, for some people, create illusory perceptions. The point is to understand that there is an ultimate reality beyond our limited dualistic awareness.

As a writer, I would argue, in fact, that the words of the Sadhana are more profound and impactful than our ability to visualize those words. After all, the point is to show a story.

Is a Novel Better than the Movie?

As any book lover or novelist can tell you, a story is best told with words, not pictures. A good novel always transcends its movie adaption. Even a great movie starts with a strong script before it is storyboarded visually.

I would argue The Lord of the Rings novels are vastly superior to the movies, even if you loved the movies. The best movie adaptions cannot measure up to the novels that inspired them. To Kill a Mockingbird may have been a good movie (1962) but the book is classic. The Color Purple and The Wizard of Oz are great movies, but nothing next to the books. The same goes for Forrest Gump, The Godfather, Doctor Zhivago, Sense and Sensibility, and Great Expectations. Don’t expect the movie producer to measure up to Charles Dickens.

Likewise, while it’s moving and powerful to visualize an Enlightened Deity in great detail — only at the end of the day to dissolve it into Emptiness — it is not as important as the spoken Sadhana. The Sadhana contains translations of the sacred words passed down by Lineage.

David Lean may have made a masterpiece movie in his 1946 Great Expectations, but he’s not Dickens. It can be nice to see the movie and read the book — although most of us prefer to read the book first.

Likewise, we should master the Sadhana, the spoken words, before we sweat over whether we can imagine it in detail in our heads. If we can never imagine the details in our head, it’s not a serious obstacle on the path to Enlightenment.

Aphantasia or Mind Blindness in Buddhism

It can be frustrating for people like myself, who aspire to the Highest Yoga Tantra Buddhist Practices but have limited or no ability of imagining pictorially in our minds. It was a comment from a Buddha Weekly reader on Facebook that inspired this feature. Our dear reader mentioned — in response to a story by Ben Christian (virtuoso artist) on how to visualize — that some people have an inability to form mind-pictures. He pointed out this was called Aphantasia or Mind Blindness.

According to Medical News Today, people with Aphantasia might not even remember the faces of their loved ones in extreme cases.[1] Even in this case, in the Buddhist practice scenario, the spoken visualization of the Sadhana should be sufficient. According to that feature, ” The aphantasia group also used more symbols and text in their renditions, often relying on verbal strategies by labeling a piece of furniture or architectural component instead of drawing the details.” [1]

In the same way, we can use verbal text and symbols as our “labeling” method and enjoy the same benefits.

Does this mean we should give up on visualized meditation altogether, and focus instead on mindfulness and other forms of meditation?

The clear answer (pun intended) is no! Basically, we still “visualize” — but we do it with the prompts of the spoken word.

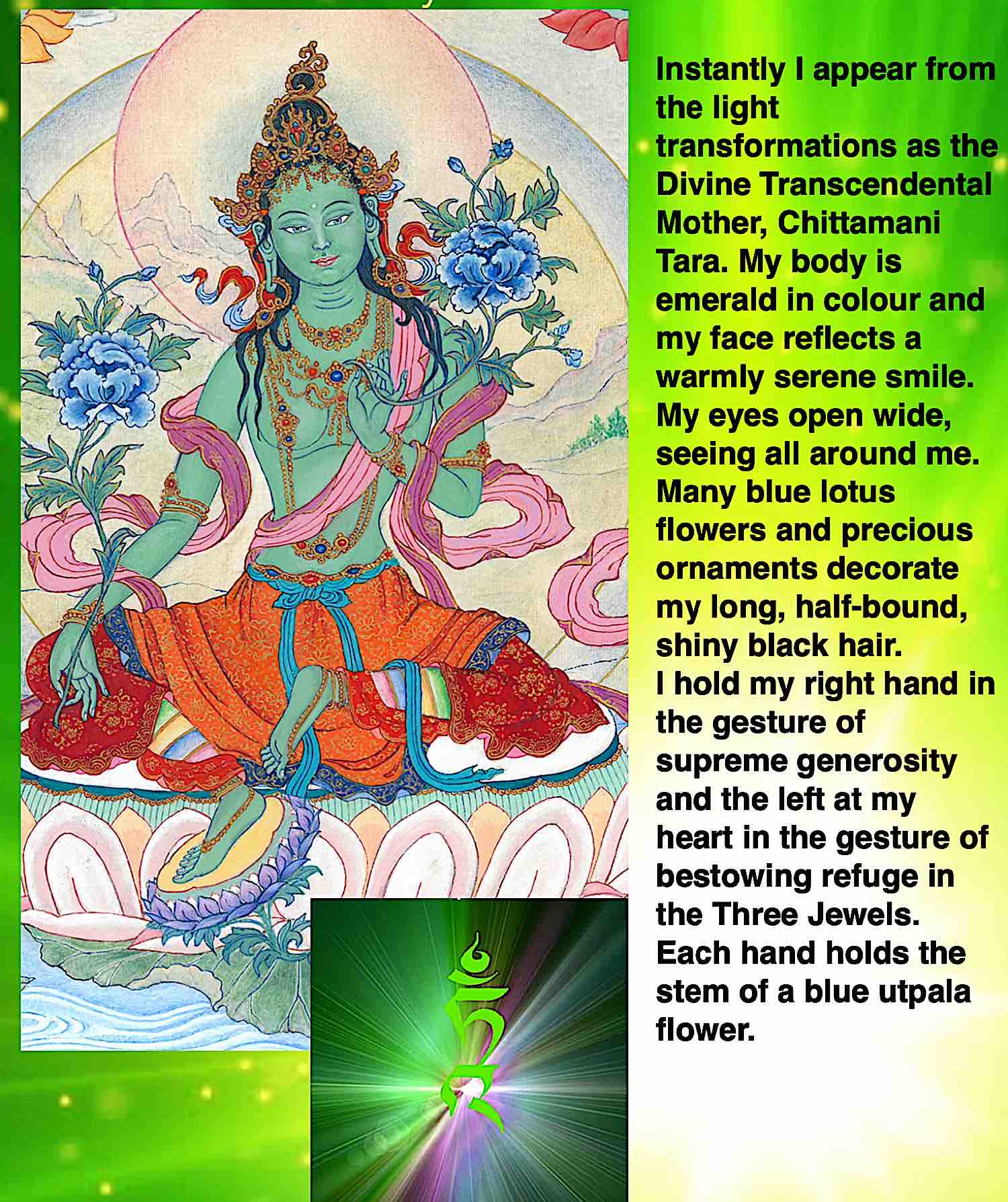

One answer, for example, is to print out the Sadhana in a more “visualized form.” For example, this is a page from the author’s daily Tara Sadhana, combining words and visualizations in a format displayed on an old Ipad:

Spending time building this in Powerpoint or any other software with “prompting” images can also be a useful memorizing practice.

Visualizations are supportive — not fundamental

First of all, it’s important to point out that Sutras are words, not pictures. Words, in fact, conjure images in our heads as we read, for example, a sutra, or a novel. Listening to an audiobook, likewise provokes a visceral response — even if you don’t vividly see pictures in your head. To illustrate this, later in this feature, I’ll quote lovely descriptions from meditative sadhanas alongside their pictures, and challenge you to decide which one is more profound and beautiful. Chances are, you’ll pick the words.

Meditations involving visualizations are supportive, but not a replacement for the sacred texts or words. Similarly, chanted mantras are a form of “word visualization” that triggers a response on our mind-stream — far more powerfully than the most stunning visualization.

Our teachers in their great wisdom — from Buddha himself more than 2500 years ago — down through the lineages of great Mahasiddhas and teachers, provided for those of us with some degree of visualization impairment. Even those of us with aphantasia, or mind blindness, can replace visualization with words. This is, in fact, why we have such detailed “practice sadhanas.” If we can see “white light goes out to all living beings” we can say it and mean it — with the same effect. Imagination, or visualization, is really just a bonus and aid.

“A Picture worth a 1000 Words”

This is actually a misquote of Henrik Ibsen, which ultimately became an adage — but, personally, I disagree; I prefer a thousand words to any picture. This is assuming 1000 perfect words against any picture. I’d prefer to pick up a sutra text and read, to watching a Youtube summary of the sutra.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, why do we still prefer to read novels and books without pictures? Or, an audiobook. The fact is, words are as profound and impactful on the mind as pictures. A picture may be preferred by some, words by another. Some of us prefer a balance of both. But, where we are unable to hold an image in our imagination or mind (mindblindness) there is hope in the poetry of words. As a writer, I’d argue, it’s more profound and more beautiful. As much as I appreciate art, I appreciate great literature even more.

All of the sutras, and most of the sadhanas given to us by our teachers, especially those that are lovingly translated, can be themselves magnificent works of prose or poetry. They evoke the same visceral responses achieved by people who can vividly imagine the same images being described. This is why the Sadhanas are written down in such detail.

Words Invoke the Same Symbolism as Images

Words can invoke wrath or peace or pacification or prosperity at least equal to — if not superior to — any form of visualization. For example, we visualize the face of compassion as Avalokiteshvara. The same feelings are evoked from the visualization found in the Avalokiteshvara Sadhana (this one FPMT translation):

“In the midst of billowing clouds of magnificent offerings,

Upon a sparkling, jeweled throne supported by eight snow lions,

On a seat composed of a lotus in bloom, the sun and the moon,

Sits supreme exalted Avalokiteshvara, great treasure of compassion,

Assuming the form of a monk wearing saffron-colored robes.”

The Sadhana then goes into great detail with every attribute and image, every aspect and nuance of his mind-environment (Mandala), every symbol portrayed.

Different Aspects and Images — as Word Symbols

These images are designed to be symbolic. Wrathful visualizations carry certain energy of overcoming “anger” with compassionate activity, for example. Red-colored bodies connote “magnetism.” These are symbols. But if I write “Red Tara” you understand this is Tara who is red and symbolism attached. Words are every bit as powerful as images.

Over the years, teachers added commentaries to the original sadhanas, which then later became part of the practices. Why? Because many of us do have difficulty with detailed visualizations.

Why are our visualization sadhanas so lengthy in word count? A simple visualization of Tonglen, or a self-generation as Avalokiteshvara can go to pages in the word count. This is not because our teachers felt the more words the better. This is skillful means. By reciting the words, either as a chant or even in English prose translation, we realize a similar benefit to a beautifully pictured mental visualization without words.

Many of us suffer from this condition, at least in part. I have heard from many readers who have difficulty visualizing. I also have this difficulty, although I can “partially” visualize. We have covered the advice of Guru Rinpoche Padmasambhava and other Gurus in a previous feature (found here>>)

Examples in Sadhanas vs Images

NOTE: In Sadhanas we normally visualize ourselves as the Buddha — a method of helping us identify with the characteristics we admire and emulate. However, generally teachers advise you NOT to visualize yourself in this way if you do not have empowerment. In this case, simply substituted “My body” with “Her body” and visualize the deity in front of yourself.

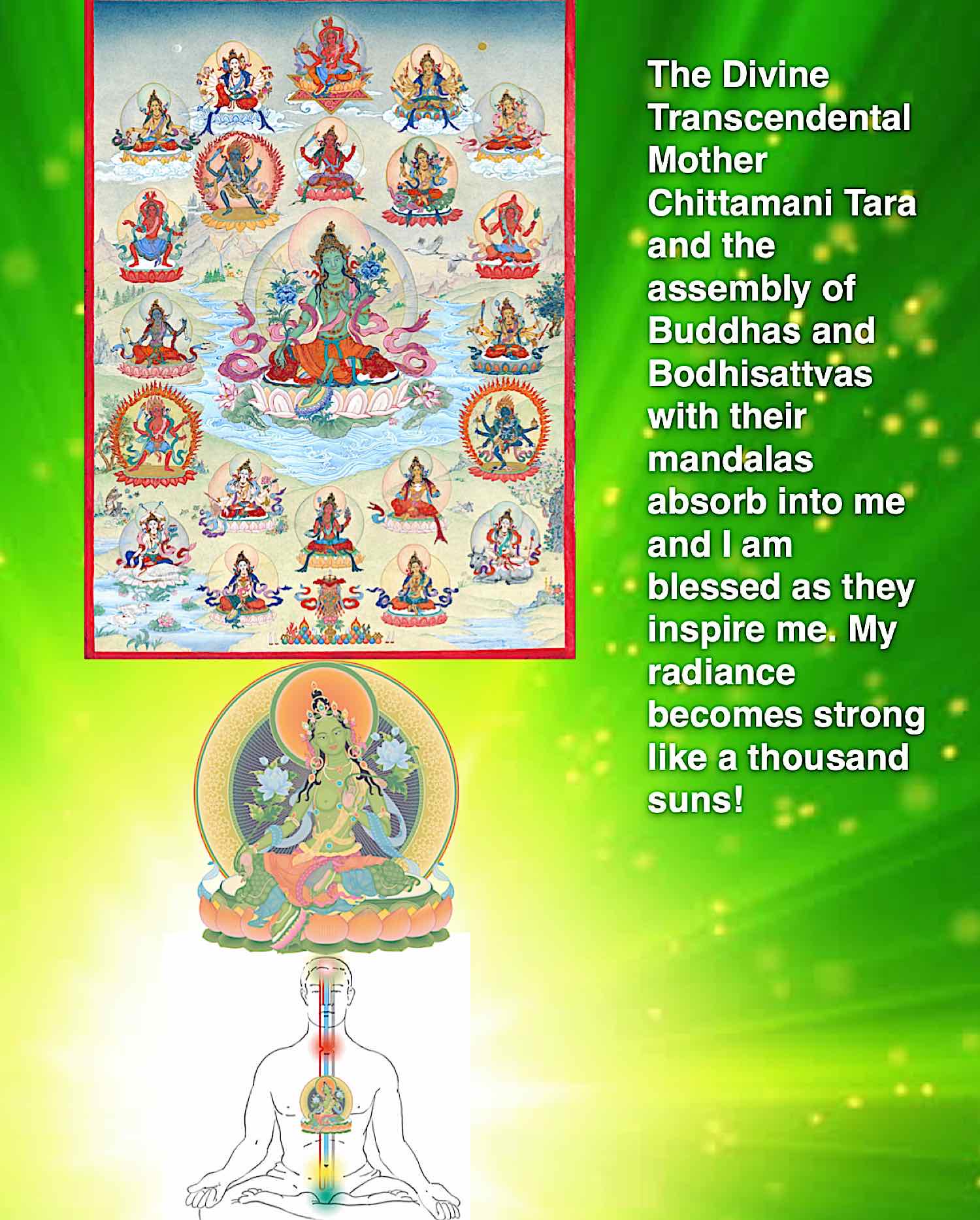

For example, in the above example of a page from the author’s “cheat sheet” sadhana, the images are alongside the words:

Instantly you appear from the light transformations as the Divine Transcendental Mother, Chittamani Tara. Your body is emerald in colour and your face reflects a warmly serene smile. Your eyes open wide, seeing all around you. Many blue lotus flowers and precious ornaments decorate your long, half-bound, shiny black hair.

You hold your right hand in the gesture of supreme generosity and your left at your heart in the gesture of bestowing refuge in the Three Jewels. Each hand holds the stem of a blue utpala flower.

Here, I have changed the language to front-generated visualization, for those without Empowerment. You think (or visualize if you can) that she arises in the form in front of you. Even if you can’t “imagine” the words evoke the beauty of Tara.

It is because of people who have trouble visualizing that the great lineage teachers added such detailed layers of visualization description. Even if I can’t “see” Tara in my mind, I can rely on the words.

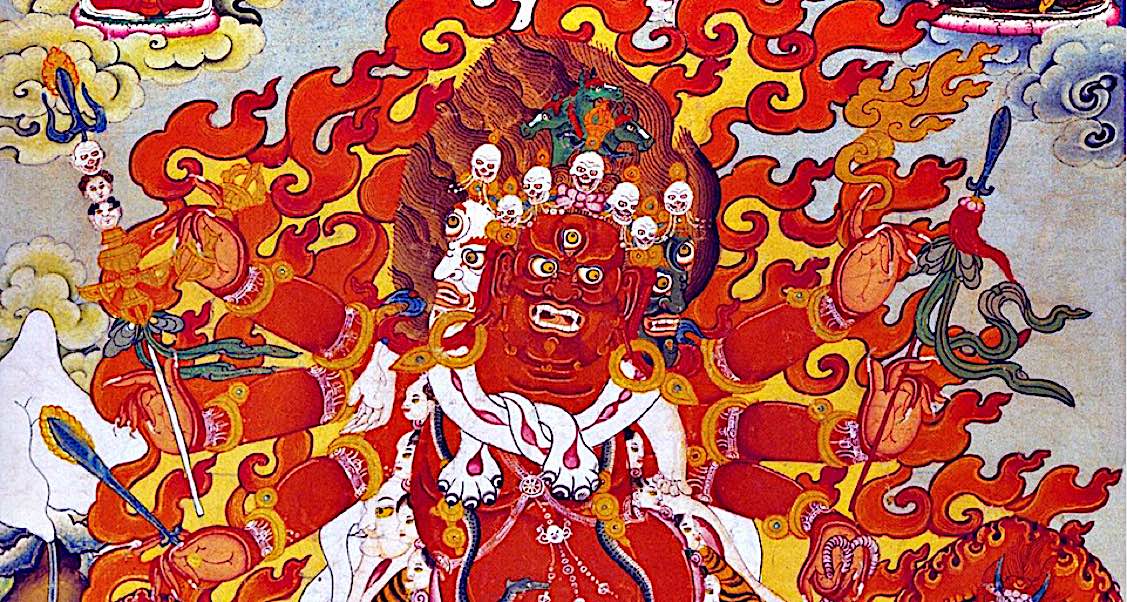

In my second example (below), Hayagriva is a wrathful emanation of Amitabha Buddha. The wrathful aspects all carry symbols: red for magnetism, three horse heads to connote activity, six arms to represent the paramitas, standing on serpents to represent suppressing illness and obstacles. Can these vibrant, evocative symbols work without the benefit of a stunning picture? Indeed yes. Here, we have a museum-quality master art painting of Hayagriva Sangdrup. Clearly, it is a powerful image, but no less impactful is the visualization verbalized in during the sadhana, which clearly evokes the same energy — and I would argue, more emphatically since in these simple words we have sounds such as “neighing horses” and “flying sparks filling the worldly realm…”:

Hayagriva, nine-gaited king, fierce and magestic, you arise from the heart of Amitabha to defeat the evil design of humans and non-human spirits… Glorious Bhagawan Hayagriva with a red-colored body, three faces, and six arms; you stand with your right legs outstretched. Your principal face is red, your right face is green, and your left face is white. Each face has three red, round eyes, and four bared fangs. On top of each head is a dark green horse head making neighing sounds, from the red mane of a male horse sparks fly filling the worldly realm…

Of course, if you are a master visualizer, you might see those animate sparks and hear the horse neighing — but the spoken words are more reliable, and beautiful.

Words — Outloud or Silently?

Words have power whether spoken or silently read. Every practitioner has their own preference. I prefer verbal, as it involves “Speech” and “Mind” both — as in, Body, Speech and Mind.” Many people whisper their sadhanas. Others do not verbalize the words at all.

NOTES

[1] Anastasia: the inability to visualize images: Medical News Today>>

More articles by this author

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Lee Kane

Author | Buddha Weekly

Lee Kane is the editor of Buddha Weekly, since 2007. His main focuses as a writer are mindfulness techniques, meditation, Dharma and Sutra commentaries, Buddhist practices, international perspectives and traditions, Vajrayana, Mahayana, Zen. He also covers various events.

Lee also contributes as a writer to various other online magazines and blogs.