Dogen, Satori, and the personal experience of enlightenment in Soto Zen: impermanence, emptiness, Zazen and “Being Time”

Soto Zen is virtually synonymous with Zazen and Mindfulness — especially uji (有時) translated as “Being Time.” [For more on “Uji” see section below.]

Soto Zen is a far-reaching, profound, and ancient path — with a particular focus on “Time Being” (mindfulness) and Zazen. In Buddhism, there as are many traditions as there are human perspectives. It has a complex history and myriad schools of thought, many focusing skillfully on methods for various preferences, attitudes, and capabilities of students. Among the many traditions, Zen, and its precursor Chan, are among the most popular. And, in Zen, Dogen and Soto Zen are top-of-mind.

One of the most influential figures in the development of Buddhist thought is Dogen, founder of the Soto school of Zen Buddhism. Dogen was a remarkable figure, revered in his time and still studied eagerly by Mahayana and Zen Buddhists today.

By Dave Lang

In this feature, we’ll explore the life of Dogen and his key teachings. We’ll also look at the impact he had on the development of Zen Buddhism and its ongoing popularity. But first, a quick refresher on the basics of Soto Zen.

What is Soto Zen?

Soto Zen is a school of Buddhism that emphasizes meditation and the personal experience of enlightenment. The school is named for its founder, Dogen, who established the tradition in Japan in the 13th century.

Dogen emphasizes the impermanence of all things and the emptiness of self. He teaches that all beings have the potential for enlightenment and that it is available to anyone who realizes this fact.

It is now among the largest traditions of Japanese Buddhism in the world.

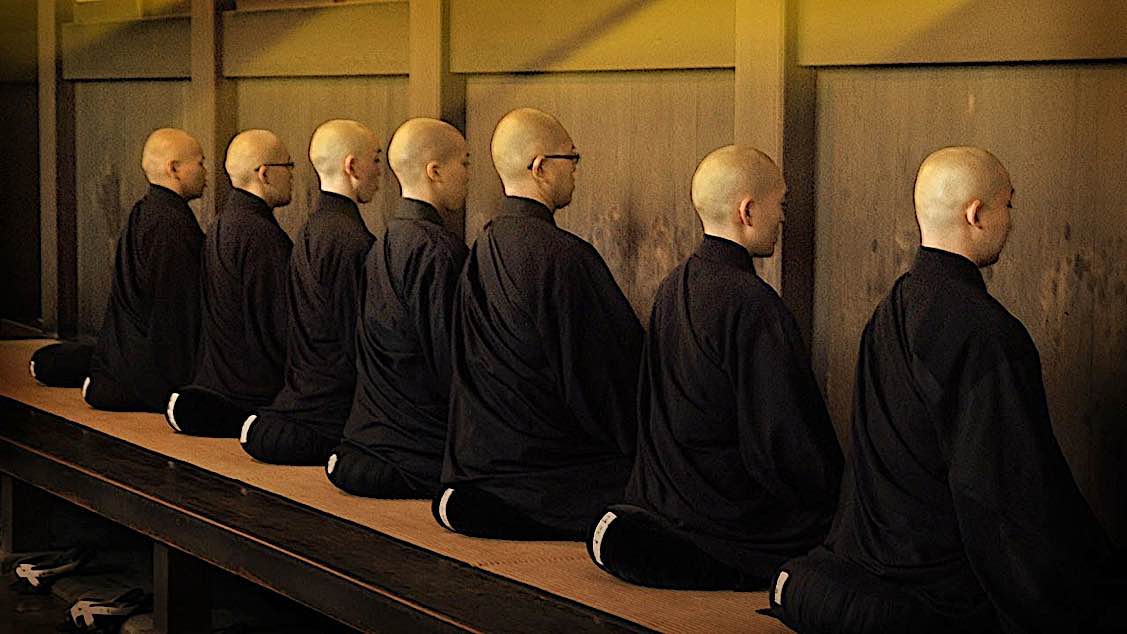

Through sitting meditation (or zazen), practitioners of Soto Zen aim to achieve

“satori,” or a sudden glimpse of enlightenment. This experience is said to be life-changing, and it is the goal of many Soto Zen practitioners.

With this in mind, let’s take a closer look at the life and work of Dogen, the founder of this influential school of thought.[1]

The Birth of a Master

Dogen was born in the year 1200 in Kyoto, Japan. His father was a high-ranking government official, and his mother was from a noble family.

Unfortunately, she is said to have passed away when Dogen was only seven years old. This tragedy would constitute Dogen’s first brush with impermanence — a central theme in his later work.

As was common for boys of his social class, Dogen began his study of important literature around the same time. As a teenager, he became fully immersed in Buddhism and began to develop his own spiritual practice.

Beginnings as a Monk

Sometime later, Dogen finds himself on Mount Hiei, the home of the Tendai school of Buddhism. Tendai Buddism was one of the most prominent schools at the time, Enryakuji being its headquarters. Dogen had come to study under the recommendation of his uncle, who was a priest.

Dogen was a great student, an ordained monk at only 14. However, he did not find the answers he was looking for at Mount Hiei.

He became frustrated with the Tendai school’s focus on scriptures and rituals, neither of which resonated with him. Dogen felt that these things only got in the way of true spiritual understanding. [2]

Around this time, Dogen had a profound experience that would change the course of his life.

Myozen and The Question That Changed it all

The source of Dogen’s frustration with the Tendai school of thought lay mainly in one question he couldn’t answer:

“As I study both the exoteric and the esoteric schools of Buddhism, they maintain that human beings are endowed with Dharma-nature by birth. If this is the case, why did the Buddhas of all ages — undoubtedly in possession of enlightenment — find it necessary to seek enlightenment and engage in spiritual practice?” [3]

Dogen wondered why someone who is already enlightened would need to seek enlightenment. For example, the Buddha was already a perfectly enlightened being, so why did he bother to seek enlightenment?

Dissatisfied with his current progress, Dogen concluded that he needed a new teacher. He left Mount Hiei and met Myozen, a Rinzai Zen Master, who would become his most important teacher. The new pair of friends studied at Kennin-ji Temple together.

Under Myozen’s guidance, Dogen developed his understanding of Zen.

Dogen’s time in China

Eventually, Dogen and Myozen decided to travel to China to study Zen in its country of origin. This journey would prove pivotal for Dogen’s development as a teacher. The passage across the East China Sea at the time was incredibly dangerous, and many people died en route.

Fortunately, Dogen and Myozen made it to China safely and began their studies at the biggest Chan monastery in Zhèjiāng province. Here, Dogan studied kōans, which are stories or questions used in Zen practice to provoke thought and help practitioners reach a state of “no-mind.”

Dogen wasn’t particularly fond of this method, as he felt that it caused the school to neglect the sutras. This is when he decides to meet with Rújìng, a Zen Master. Dogen was so impressed by Rújìng’s teaching that he referred to him as the ‘Old Buddha.)

This period of his studies becomes critical as he fully absorbs the teachings of his new master. Five simple words would forever change the course of Buddhist history.

“Cast off body and mind.”

These words would come to shape Dogen’s entire understanding of Buddhism and his practice. He came to the realization that meditation isn’t about texts and prayers but rather letting go of the idea that there is a separate ‘self’ that can be enlightened.

In his texts, he often would use the expression ‘dropping body and mind.’ That meant that practitioners should let go of their attachment to the body and the mind and the idea of a separate self.

Myozen’s Death

Shortly after Dogen’s revelation, Myozen dies of an illness. Dogen is heartbroken, but he remains in China to finish his studies. In 1227, he claims to have completed his quest and returned to Japan.

Eihei-ji: the Temple of Eternal Peace

In Japan, Dogen is on a mission to spread his newfound understanding of Zen. He starts by building a small temple called Eihei-ji, which roughly translates to ‘The Temple of Eternal Peace.’

This is where Dogen hones his skills as a teacher. He often gave talks that lasted for hours, and he wrote extensively on Buddhist principles. Dogen’s teachings began to attract more and more followers, and eventually, Eihei-ji became one of the most important Zen temples in Echizen.

However, there was tension from the beginning as many of the monks at Eihei-ji were former Tendai monks from Mount Hiei. They were used to a different way of life and found Dogen’s ascetic practices too extreme.

Despite the opposition, Dogen continued to teach and write, and his work began to garner attention from some of the most important figures in Japanese Buddhist history. One of his most famous students was Koun Ejo, who would later succeed him as the head of Eihei-ji.

A few months later, Dogen’s flame was extinguished all too soon. He passed away in 1253, at the age of 54, from an unknown illness.

Dogen’s Legacy — Writings and Teachings

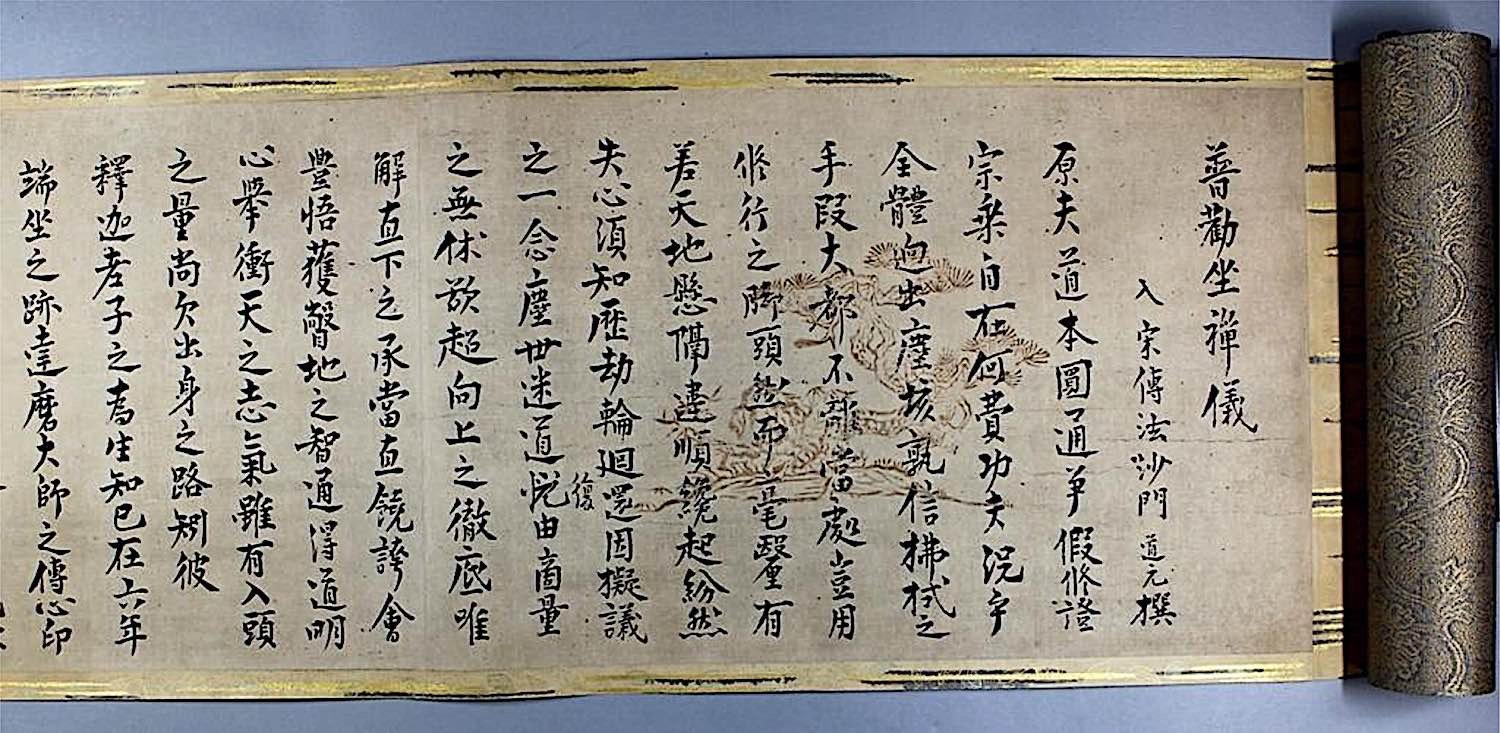

Dogen leaves behind a considerable corpus of work, most of which was only published posthumously. His two most famous works are the Shobogenzo and the Eihei Koroku. His work is of undeniable influence on Buddhism. [5]

Shōbōgenzō — “Treasury of True Dharma Eye”

The Shōbogenzō (Japanese: 正法眼蔵 “Treasury of the True Dharma Eye”) is Dōgen’s magnum opus, consisting of 95 chapters, each of which is a complete essay in itself. The work covers a vast range of topics, from the mundane to the metaphysical. It’s considered one of the most important works of Japanese Buddhist thought and has been highly influential in the development of Zen.

The Shōbōgenzō Zuimonki (Japanese: 正法眼蔵随門記 “The Treasury of the True Dharma Eye: Record of Things Heard”) is a collection of Dōgen’s talks recorded by his successor Koun Ejo. It gives insight into his daily life and his thoughts on various topics, such as meditation, teaching, and the nature of reality.

Eihei Koroku — Dogen’s collection of talks

Dogen’s other major work is the Eihei Koroku, a collection of his talks and sermons. It provides insights into Dōgen’s thinking on various topics, such as meditation, enlightenment, and Buddhist cosmology.

Dogen’s writings have had a profound impact on the development of Zen Buddhism in Japan. His ideas on practice, enlightenment, and non-duality have shaped how Zen is practiced in Japan to this day.

Dogen’s teachings also continue to inspire and challenge practitioners worldwide.

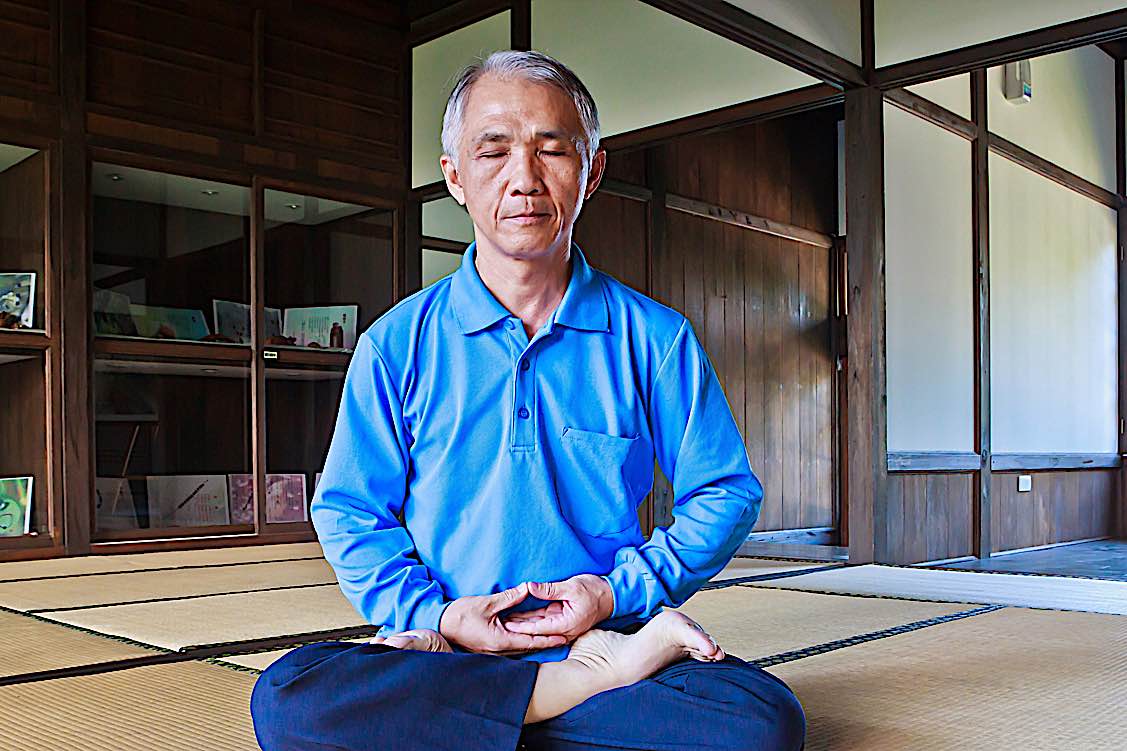

“Studying Zen … is Zazen” – Dogen.

Dogen’s most famous teaching is zazen, which is a meditation practice. He believed that zazen was the key to understanding the true nature of reality. He believed we shouldn’t need incense, candles, or other fancy props to help us meditate; we should be able to do it anywhere, anytime.

Dogen also believed that zazen wasn’t just a practice for monks; it was something that lay people could do as well. In fact, he believed that zazen was the key to understanding the true nature of reality, and he taught it to anybody. From aristocrats to farmers, Dogen’s students came from all walks of life.

Sitting meditation is at the heart of Zen practice. It is a way to calm the mind, body, and spirit. It is a way to connect with our true nature. It consists of sitting with our spine straight, eyes open or closed, and hands resting on our laps with our palms up. We focus on our breath and let thoughts come and go without judgment.

You shouldn’t aim to achieve anything while meditating; just let the practice be what it is (gainless zazen.)

Buddha-Nature

Dogen also taught Buddha-Nature, which is the inherent potential to attain enlightenment. This teaching is based on the Diamond Sutra, a key text in Mahayana Buddhism. The Diamond Sutra says that “sentient beings are innately endowed with the Buddha-nature.”

Impermanence comes back into play here as well. Dogen believed that because everything is impermanent, it is constantly changing. This means that even if we achieve enlightenment, it is not something that we can hold onto.

The Buddha-nature is often compared to a seed. Just as a seed has the potential to grow into a tree, we all have the potential to attain enlightenment. But like a seed, it takes time, effort, and proper conditions for this to happen.

Dogen’s teachings on the Buddha-nature emphasize the importance of practice. He believed that we need to put in the effort to cultivate our Buddha nature. This is why he placed such importance on the zazen.

“Being Time” — Dogen’s unique perspective

Dogen also has a unique way of looking at the time, which he called “being-time.” Being Time is a way of being in a world based on the present moment. It’s the idea that time isn’t something that happens to us; it is something that we are. Being, in this very moment of time.

That means we shouldn’t try to control time; we should let it be. We can’t hold onto the past or the future, so the only thing we have is the present moment.

The Japanese keyword uji has more meanings than any single English rendering can encompass. Nevertheless, translation equivalents include:

- Existence/Time

- Being-Time

- Being Time

- Time-Being

- Just for the Time Being, Just for a While, For the Whole of Time is the Whole of Existence.

- Existence-Time

- Existential moment.

“Time-Being” carries a slightly different connotation — typical with Dojen who wrote very cleverly with multiple meanings in every sentence.

The present Shōbōgenzō fascicle (number 20 in the 75 fascicle version) commences with a poem (four two-line stanzas) in which every line begins with uji (有時):

“An old Buddha said:

For the time being, I stand astride the highest mountain peaks.

For the time being, I move on the deepest depths of the ocean floor.

For the time being, I’m three heads and eight arms [of an Asura fighting demon].

For the time being, I’m eight feet or sixteen feet [a Buddha-body (Dharmakaya) while seated or standing].

For the time being, I’m a staff or a whisk.

For the time being, I’m a pillar or a lantern.

For the time being, I’m Mr. Chang or Mr. Li [any Tom, Dick, or Harry].

For the time being, I’m the great earth and heavens above…”

We can apply this way of thinking to Dogen’s approach. Students shouldn’t try to achieve anything in practice; they should just let it be. Zazen is a way to connect with the present moment. It is a way to be with time-being.

Getting Started With Soto Zen

If you’re interested in getting started with Soto Zen, there are a few things you should know.

First, it is always best to find a teacher. It is challenging to learn Zen without the guidance of a teacher, as even Dogen needed to go out and find a good one. A good teacher can help you understand the teachings and put them into practice.

Once you find a teacher, you can begin to learn about the practice. Soto Zen is based on the teachings of the Buddha and the great Zen masters. It is a way of life that emphasizes compassion, wisdom, and mindfulness.

The main exercise of Zen is based on Zazen, or sitting meditation, but it also includes other things such as eating mindfully, walking meditation, and working mindfully.

Final Thoughts

Dogen was a remarkable man and an important figure in developing Buddhist thought. His life and work continue to inspire Buddhists around the world. We hope this article has given you a taste of his teachings and why they remain relevant today.

If you’re interested in learning more about Buddhism as a religion or its historical figures, feel free to visit the rest of our blog.

Sources

[1] https://www.sotozen.com/eng/library/journal/index.html

[2] https://www.zen-deshimaru.com/en/zen/biography-zen-master-eihei-dogen-1200-1253

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/D%C5%8Dgen

[4] https://www.jstor.org/stable/41884889

[5] Uji “Being Time” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uji_(Being-Time)

More articles by this author

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Dave Lang

Author | Buddha Weekly

Dave Lang contributes to several online magazines. He is Buddhist, more or less a "Chan Buddhist" — and his special bow goes to Bodhidharma, his Dharma Hero. He is also an avid martial artist.