Deity Yoga: Science or Superstition? Vajrayana Deity Meditation Proves Invaluable in Preventing Cognitive Disorders. In What Other Ways is Vajrayana Buddhist Deity Practice More Science than Religion?

Deity Yoga in Tibetan Buddhism is very often misunderstood. In apparent contradiction to the implied meaning of “deity” — which is really a mistranslation of the Sanskrit “deva” — there might, in fact, be more science than superstition to the practices of deities. It’s a ridiculous notion, I know, but one I hope to support at least on a practical level — please, bear with me.

Thousands of years ago, Shakyamuni Buddha taught a self-help path to Enlightenment, which included many parallels to modern scientific method. As recorded in the Kalama Sutta, Buddha said: “it is proper that you have doubt… do not be led by reports, or tradition or hearsay.” A scientific method clearly.

In fact, Buddhism is often described as the “pure science of mind.” [1] Thousands of years before Einstein, Buddha already taught the notion of relativity — at least in the sense of relative truth versus ultimate truth, and concepts such as Emptiness. (I know that has nothing to do with E=MC2, but I’m having fun with this.) While I’ll admit that’s a stretch, the Heart Sutra’s teachings on Emptiness parallel some of science’s later theories as embodied in Quantum physics.

Einstein: “a kind of delusion of consciousness”

Although quoting Einstein is a perilous area these days — most quotes attributed to Einstein online are false (as are many of Buddha’s) — never-the-less one significant quote is worth repeating as a foundation to this premise. It was originally quoted by the New York Times March, 29, 1972, and is also found in “The New Quotable Einstein” and presents a most Buddhist-like view:

“A human being is a part of the whole, called by us “Universe”, a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separated from the rest — a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty. Nobody is able to achieve this completely, but the striving for such achievement is in itself a part of the liberation and a foundation for inner security.” [6]

Even if we accept that Buddhist philosophy and science can be complementary, what does all this have to do with Deity Yoga? Why meditate on deities at all? What could possibly be scientific about deities?

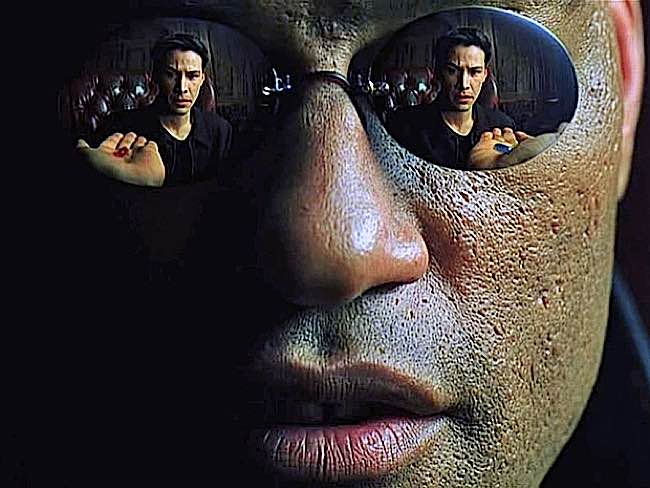

The Matrix: “There is no spoon”

It’s fine to point to some loose parallels between Buddhist thinking and modern quantum theories, or to use ancient meditation methods in modern medical treatments. But isn’t there more superstition than science to things such as popular Tibetan Buddhist Deity Yoga practices? In colorful language, the Tantras describe a vast cosmos filled with millions of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Dakinis, Dakas, Protectors, Pure Lands, gods, goddesses, and even speaks of hell realms, zombies, hungry ghosts, and terrible demons. How can this be anything but superstition and religious dogma?

Deity practice is a visualized meditation that helps us work on our own minds. It is not the “I” pleading with the “other” (i.e. deity) — which would be religion or faith — but rather, the “I” trying to see things as they really are.

The advanced concept of Emptiness is important in understanding that deity yoga is not about fantasy worlds of gods and demons. Emptiness — not to be confused with nihilism — in part acknowledges the fallacy of inherent existence. Emptiness is a vast topic, discussed elsewhere, but it is a concept that must be embraced to even practice Deity yoga. Neither the self nor the deity have inherent existence.

[For a Buddha Weekly feature on Emptiness, see>>]

In the movie The Matrix, in a scene with a young monk who can bend spoons with his mind, the young monk says, “Do not try to bend the spoon — that’s impossible. Instead, only try to realize the truth.” Neo, the protagonist, asks, “What truth?” The monk says, “There is no spoon.” The entire movie is a journey into seeing the world as it really is.

In Vajrayana, or Tantric Deity practice, one of the goals is to help our minds break down “ordinary appearances” and understand them for what they really are.

In the most recognizable scene in the movie the Matrix, Neo’s “teacher” Morpheus asks him to take the blue pill or the red pill. “You take the blue pill, you wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe. You take the red pill, you stay in wonderland and I show you how deep the rabbit hole goes.” Vajrayana is the red pill.

Alexander Berzin: “Transforming minds and attitudes”

A key goal of Tantric Deity Practice is “transforming the I.” Deity practice is not an act of worship. Although there’s an element of praise, in Deity Yoga, the practitioner visualizes him/herself as the Enlightened Deity, which is a visual symbol of the Enlightened state we aspire to. Alexander Berzin describes it as: ” The actual practice entails transforming our minds and our attitudes.” [8]

He explains: ” Therefore, we imagine ourselves in the form of a Buddha-figure, similar to the type of body that we would have as a Buddha. And all the various arms and faces and legs, the multiple figures within the mandala – within the configuration that we are imagining – all these represent different aspects of understanding or realization, like the six far-reaching attitudes (the six perfections) and so on. By representing them graphically, it helps us to actually keep all of these in mind at the same time, which is what we need to do as a Buddha, and what we need to do even as a bodhisattva beforehand trying to actually help others.”

Tantric deity yoga begins and ends with meditation on Emptiness, to reinforce that the deity, like we ourselves, is empty of inherent, independent existence. This helps us to “transform the I.”

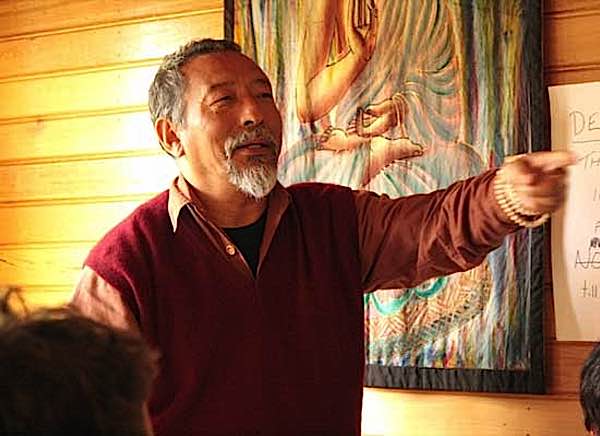

Zasep Tulku Rinpoche: “You transform the I… ordinary man or woman is already gone”

In a wonderful interview with Buddha Weekly, Acharya Zasep Tulku Rinpoche, spiritual head of Gaden for the West and Gaden Choling, explained how in Deity practice we always start with a meditation on emptiness, acknowledging all things, self and deity, are ultimately empty: “…every time you do any of these practices, first you meditate on emptiness.

“You start with the Sanskrit mantra, Om Svabhava Shuddo, and so on, “everything becomes voidness.” Then you visualize your consciousness arising as a seed syllable, then the deity. So, when you do these practices, this “I” — ordinary man or woman ego — is already gone. You transform the I, or ego, by meditating on emptiness. When there is no self, who is there to be angry? Who is there to be terrified?”

Deity yoga are advanced practices in Buddhism. However, all Tibetan schools emphasize beginning these practices with traditional foundation practices, Lamrim and sutra study, Vipassana and Samatha meditation, and many other non-deity practices. Rinpoche explained: “You need a good base in Sutra and Lamrim practice.”

Rob Preece: Deity Yoga, the “language of psychological symbols

Tantra conveys concepts in a visual language of symbols and metaphors. Rob Preece, a psychologist, explained deity mandalas this way: “The images we normally associate with the mandala are significant psychological symbols of what Jung called the Self… In tantric mandala, these symbols represent a complete re-creation of the totality of the psyche on a symbolic level.” [7]

In other words, deities are enlightened visual expressions, used in meditation to transform our own egos. In Buddhism, we honor the body, speech and mind of Buddha. Enlightened mind is — at the ultimate level — one essence, regardless of manifestation as this or that deity. In other words, Tara, Vajrayogini, Avalokitesvara, and all the deities, at an ultimate level are one essence, or put another, have all the same qualities of Enlightenment. Manifestation as visual deities are “body” of Buddha — but ultimately these too lack “inherent existence.” The speech of the Buddha is Dharma, the teachings, which include sophisticated concepts such as emptiness.

Buddhism: “Deliberately NOT Seeking Refuge in Dogma and Superstition”

Throughout history, Buddhism has remained the “impartial investigative” spiritual path, deliberately not seeking refuge in dogma, magic, superstition. Non-Buddhists (and Buddhists) are often confused by the seeming contradiction of an vast pantheon meditation deities: Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Deities, Yidams, and so on. There is no contradiction. Buddha taught by skillful means, different methods for different students. Vajrayana deity meditation is an important practical method to accomplish realizations on the nature of reality.

Medicine and psychiatry, has embraced Buddhist meditation methods: as reported by Buddha Weekly previously, Vajrayana Deity meditation has cognitive benefits, possibly even strong potential for people with various forms of dementia. Mindfulness meditation, as taught by Buddha, is a commonly used method in various medical areas, notably psychological therapy, and stress relief. Buddhist sutras, long before Democritus formulated his atomic theory of the universe in Ancient Greece, spoke of an atomic world, and a Universe of many dimensions (similar to some Quantum theories).

Famously, the Dalai Lama has embraced science and often speaks of parallels between Buddha’s teachings and science. In particular, quantum physics and Buddhist understanding are often seen as very reinforcing and complimentary.

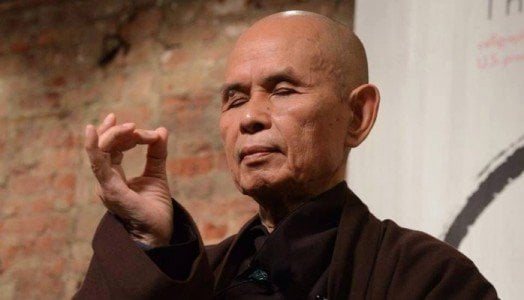

Thich Nhat Hanh: Buddhism and Science

Buddhist method in other ways mirror science, not only in the most basic premise — that of “cause and effect — but in most substantive ways. The great Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh wrote:

“In science, a theory should be tested in several ways before it can be accepted by the scientific community. The Buddha also recommended, in the Kālāma Sūtra, that any teaching and insight given by any teacher should be tested by our own experience before it can be accepted as the truth. Real insight, or right view (S: samyag-dṛṣṭi, C: 正見), has the capacity to liberate, and to bring peace and happiness. The findings of science are also insight; they can be applied in technology, but can be applied also to our daily behavior to improve the quality of our life and happiness. Buddhists and scientists can share with each other their ways of studying and practice and can profit from each other’s insights and experience.” [2]

Christian Today: “Plethora of Celestial Beings”

One of my Google alerts on “Buddhism” triggered the idea for this feature. The alert picked up a highly critical feature on Christian Today putting forward the premise “3 common misconceptions about Buddhism.” [4] Amongst the many misconceptions listed in that feature by junior writer Florence Taylor, she described how she viewed Buddhist deities: “although Buddhism doesn’t speak of God in a Judeo-Christian sense — it does have an elaborate plethora of celestial beings who exist in various heavens and respond to the prayers of the devout.” In an interesting twist, this — together, with most of her listed “misconceptions” — were themselves misunderstandings.

It’s been four decades since I was “outside Buddhism looking in,” but this reminded me that I myself might have once held this view. Not only non-Buddhists, but some Buddhists themselves, might similarly misunderstand the practice of deities.

Since Buddhism generally doesn’t embrace dogma — often presenting different approaches and “skillful means” that can even seem contradictory — it has room for everyone: from scientists, to atheists, to those seeking wisdom and personal Enlightenment in meditative practices, even to those who are more comfortable worshiping deities. Buddhists who identify as atheists might practice analytical meditation, while, in contrast, some Pure Land practitioners might devoutly worship enlightened beings.

Misunderstanding Starts with Mistranslation of Deva or Lha

The practice of deities is not, generally, as described by Florence Taylor. The root of the misunderstanding is likely the very word “deity”, an unfortunate early English translation of Sanskrit “deva” and Tibetan word “Lha” that misses the mark. Yidam, or “enlightened heart being”, is closer to the Mahayana view of “deities.” Deva literally means “divine” while “lha” (pronounced hla) literally means “higher.” [3]

The practice of deities is not, generally, as described by Florence Taylor. The root of the misunderstanding is likely the very word “deity”, an unfortunate early English translation of Sanskrit “deva” and Tibetan word “Lha” that misses the mark. Yidam, or “enlightened heart being”, is closer to the Mahayana view of “deities.” Deva literally means “divine” while “lha” (pronounced hla) literally means “higher.” [3]

Generally, divine in Sanskrit and “higher” in Tibetan refers to the “higher self” not generally a “higher external self-aware being.” Gods entirely misses the mark, as in a self-aware autonomous external being. Deities in Buddhism can be viewed different ways, but the very basis of Buddhist thinking, particularly concepts of non-duality and self.

Science or Religion? Neither?

Perhaps the original premise is wrong. It’s not a clear cut dualistic choice: science or religion. Buddhism is far from dualistic. Science is also probably the wrong choice of words. So is religion. Neither really suits Buddhism. Buddhism is generally not a religion of dogma and worship. On the other hand, a true scientist would laugh at the very idea that Buddhism is scientific. Yet, Buddhism is, ultimately, and intimately, a personal journey. Science, religion, practical or whimsical — it’s pretty much up to the individual. Yet, what is a certainty, is that deity practice is not superstition or magic. The practice of deity is the practice of discovering the true nature of things. On our own terms. At our own pace. With no rights and wrongs.

NOTES

[1] “Work out your own Salvation” by S.N. Geonka

[2] From archives of Plumvillage.org

[3] “Lha or is it La“? Nalanda Translation Committee

[4] “Is Buddhism really peaceful? 3 common misconceptions about Buddhism.” junior writer Florence Taylor

[5] “Dhamma and Non-Duality” Bhikkhu Bodhi

[6] The New Quotable Einstein by Alice Calaprice (Princeton University Press, 2005: ISBN 0691120749), p. 206 and attributed to a letter of 1950, quoted by The New York Times March 29, 197 and by the New York Post November 28, 1972.

[7] The Psychology of Buddhist Tantra, Rob Preece (Kindle edition) location 2486

[8] “Session Six: Differences between Sutra and Tantra“: Alexander Berzin

More articles by this author

Guru Rinpoche is ready to answer and grant wishes: “Repeat this prayer continuously” for the granting of wishes

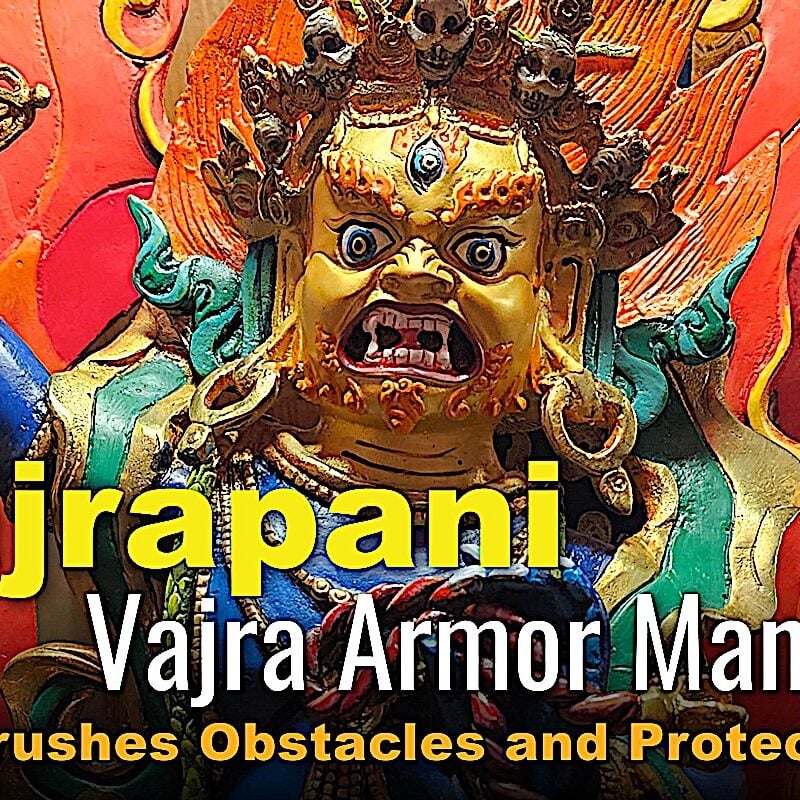

VIDEO: Vajrapani Vajra Armor Mantra: Supreme Protection of Dorje Godrab Vajrakavaca from Padmasambhava

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

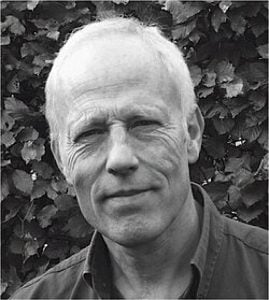

Lee Kane

Author | Buddha Weekly

Lee Kane is the editor of Buddha Weekly, since 2007. His main focuses as a writer are mindfulness techniques, meditation, Dharma and Sutra commentaries, Buddhist practices, international perspectives and traditions, Vajrayana, Mahayana, Zen. He also covers various events.

Lee also contributes as a writer to various other online magazines and blogs.