Overcome the Poison of Hatred as taught by Buddha in Sutra; How to Cultivate Advesha

Hatred is the most potent of the three poisons, considered more dangerous than greed and ignorance.

Buddha taught many ways to supress hatred, and especially emphasized advesha — “absence of hatred” methods.

Hatred is often our way of reacting to suffering, and it is not necessary to feel the need to distinguish between worthy and not-so-worthy objects of our hatred. Sometimes, we just feel the need to hate someone.

What can Advesha do for us?

Advesha or the absence of hatred means, firstly, that we do not want to hurt people who have not given us a reason to hate them.

Special Feature by Donald Mena

(Bio below.)

Advesha, or absence of hatred, also means that we are not angry at unsatisfying situations, which ultimately means that we are not enraged even by the inevitable decline and destruction of things, or impermanence. (Hatred is the klesha known as “dosa.”)

Thirdly, it means that we do not feel malicious towards people who hurt us, even if they do it consciously. Advesha means that we do not react to suffering in any of these ways. Although hatred creates suffering – in so far as hatred immediately causes pain – suffering should not lead to hatred. Instead, we can develop advesha.

- This is part of our series on the 10 poisons. For part 2, which focused on “Greed” see>>

- Part 1 of this series gave an overview of all ten poisons>>

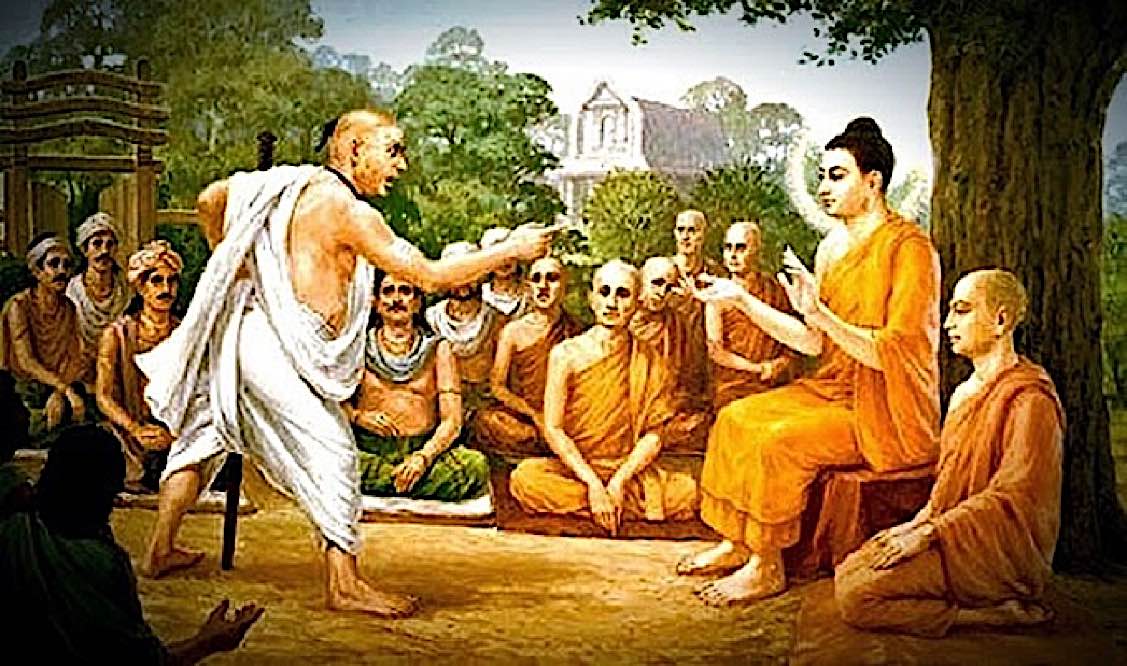

- Buddha and the “angry man” is a classic sutra story illustrating anger>>

We do not create conditions for hatred in others

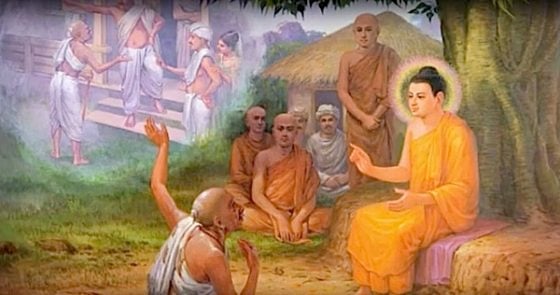

Advesha — a lack of intent to cause harm — also means that we do not create conditions for hatred in others. Hatred breeds hatred, it is contagious. Hatred makes us and others suffer, and this suffering leads us and other people to new hatred and new suffering. This is quite obvious: we do not cause suffering directly, we do not deprive someone of what they value, because, among other things, to do so would be to cause hatred in others.

However, in a quote from the Vijnaptimatratasiddhi-sastra, there is a conclusion that a person can become an object of hatred simply by being impermanent. You can be completely devoted to someone throughout your life, but when you die, the person you left behind may feel hurt, as if it’s your fault. “Why did this have to happen to me? – they ask. “Why did you have to die right now when I need you so much?” It’s unreasonable, but it happens.

Resentment in itself is unreasonable. Even if someone gets into an accident or faces an illness without being to blame for it, and needs to be taken care of, the one who has to do it seems to naturally feel offended from time to time. This does not mean that we are responsible for the fact that others hate us: even Buddha was hated by some.

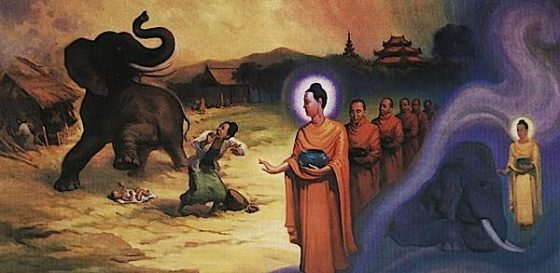

- The classic sutra story of compassion as a remedy for the poison of hate is the story of mass-murderer Angulimala who tried to kill Buddha. Not only did Buddha remedy his life-taking hate, he took him in as a disciple. Read the full story here>>

Hatred and attachment are connected

There is a close connection between hatred and attachment. It is probably most obvious in the context of sexual relationships. Perhaps we can say that where there is an attachment in sexual relations, sooner or later hatred will arise. Are they so amazing, these terrible fights and quarrels that break out between partners? This is the inevitable fruit of attachment. If there are no outbursts of anger, if you can live for several years without hatred breaking out, without slipping into a routine, most likely there is no strong attachment between you, and the relationship is more or less healthy.

“When a good mind is born, whatever the object of its perception, it always manifests itself as non-attachment with existence and absence of discontent to suffering. This means that the absence of greed and the absence of anger is strengthened with “existence” and “suffering”, but the mind does not need to remember existence and suffering to manifest these two Chaittas. Similarly, the sense of shame and integrity is strengthened with good and bad, but the mind does not need to feel good and bad to manifest these two Chaitas. It follows from this that the absence of greed and anger accompany all good minds”.

— “Vijnaptimatratasiddhi-shastra”

All these concepts — shame, fear of censure from the wise, non–attachment, and absence of hatred — represent the positive state of the mind and not just negative events of the mind that somehow could not be realized. To experience or manifest them, we do not need to feel inclined to something shameful or reprehensible, to feel on the verge of attachment or disgust.

We may be confused by the fact that grammatically negative expressions are used for positive qualities, but this is a common characteristic of Pali and Sanskrit: adding a- as a prefix creates a negative equivalent of the word, just as the prefix non- does it in English (so we have dvesha, which means hatred, and advesha, which means non-hated, non-hate).

In English, this “double negation” is rarely used for positive qualities. But there is one obvious example of an English word that is created in this way – the word immortal, “immortal”. It means “no mortality”, but in itself, of course, has a very positive meaning. In such expressions as “the absence of hatred”, you also need to see similar positive shades.

Non-hate is not just the absence of hate

But if “non-hate” is not just the absence of hate, if it is a positive quality in itself, why not call this quality, say, just love or maitri (metta in Pali)? It makes sense to express certain qualities through their opposite, since they become difficult to achieve as a result, which is very important for their meaning. Yes, it is difficult to break through negative terminology to these qualities, but in fact, it is not so bad. When faced with such “negative” terms, we must ask ourselves: “What is meant here?”

The word itself does not allow us to imagine that we know everything about it, simply because we know the meaning of the word. We begin to understand that we must experience this very quality – alobha or advesha – as an experience to understand what it is.

It is not enough just to understand the meaning of the name. And there is a difference between these “negative” expressions and their positive equivalents. For example, loving-kindness goes beyond the absence of hatred.

If you are in a situation where someone is causing you great difficulties or inconvenience, you can feel the absence of hatred without necessarily feeling loving-kindness, which suggests that these are two different states of the mind.

While the absence of hatred and the absence of attachment support each other – because there is no hatred without attachment, and attachment without hatred – both are born only by the non-obscurity, the next state of the mind. Together, these three fundamental positive events of the mind form the three beneficial roots of all positive actions.

The principle of abstinence from hatred — Compassion

The true nature of the non-hurtful state of consciousness, which concerns the Ninth Instruction, can be understood only by establishing a connection between the concepts of “Hatred” and “Greed”. While greed is a state in which the “I” or ego expresses its attitude towards the “not-I” or “not-ego” in the form of a desire to appropriate it or even make it a part of itself, hatred is a state that arises if such an attitude is detected, prevented or suppressed by itself “not-me” or “not-ego”, or by another person or factor. Therefore, if greed is a primary psychological state, then hatred is a secondary one. It manifests itself in the form of a deadly desire to cause as much harm and damage as possible to everything that comes between the hungry subject and the object of greed.

As for the positive opposite of the principle of Abstinence from Hatred, it is not Love, as it would be logical to imagine, but Compassion. The term Love is already used as the positive opposite of Abstinence from Killing, but the main reason that the word Compassion is used in this case, and not Love, is that the positive opposite of Abstinence from Hatred is contained in the concept of the Bodhisattva Ideal.

Neglect under influence of anger is a serious violation

According to the text of Upali-pariprichcha or “Questions (Arhat) Fell”, in the Mahayana Ratnakuta Sutra, for a Bodhisattva, neglect of instructions under the influence of desire (= greed) is considered a minor violation, even if it occurred in many kalpas, whereas even a single case of neglect of any instruction under the influence of anger (=hate speech) is considered a very serious violation.

The reason is that “A Bodhisattva who does not follow instructions because of desire [still] holds sentient beings in his arms, and a Bodhisattva who does not follow instructions because of hatred renounces them all.”

In this episode, however, as in all others, Mahayana does not at all assert that neglecting instructions because of desire is not essential, but emphasizes that it is extremely important for a Bodhisattva not to renounce sentient beings, under any circumstances, but neglecting instructions because of hatred, he does exactly that. Hatred and compassion are mutually exclusive. Therefore, “Compassion” and not “Love” is the positive opposite of Abstinence from Hatred.

About the author: Donald Mena is a writer, psychologist, and meditation enthusiast. He studies ancient Buddhist texts and is a contributor to Bidforwriting.com, where you can get help with academic writing. (This feature was not requested — and was submitted under Buddha Weekly’s standard writer terms.)

More articles by this author

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Donald Mena

Author | Buddha Weekly

About the author: Donald Mena is a writer, psychologist, and meditation enthusiast.He studies ancient Buddhist texts and is a contributor to WritingAPaper, where you can get help with academic writing.