The Lion’s Gaze and the Lion’s Roar: Padmasambhava, Milarepa and Buddha’s lion wisdom even more relevant in today’s hectic world

The Lion’s Gaze parable is, perhaps, more meaningful in today’s hectic world, than it was in Ancient Tibet. Today, anger, fury, social unrest, and dissatisfaction make The Lion’s Gaze a very relevant gem of ancient Buddhist wisdom. Mainly, when we feel paralysed by choices — including choosing the best of bad choices — this insight can be beneficial. Fully understood, this nugget of wisdom become very relevant today:

“When you run after your thoughts, you are like a dog chasing a stick: every time a stick is thrown, you run after it. Instead, be like a lion who, rather than chasing after the stick, turns to face the thrower. One only throws a stick at a lion once.” -Milarepa [1]

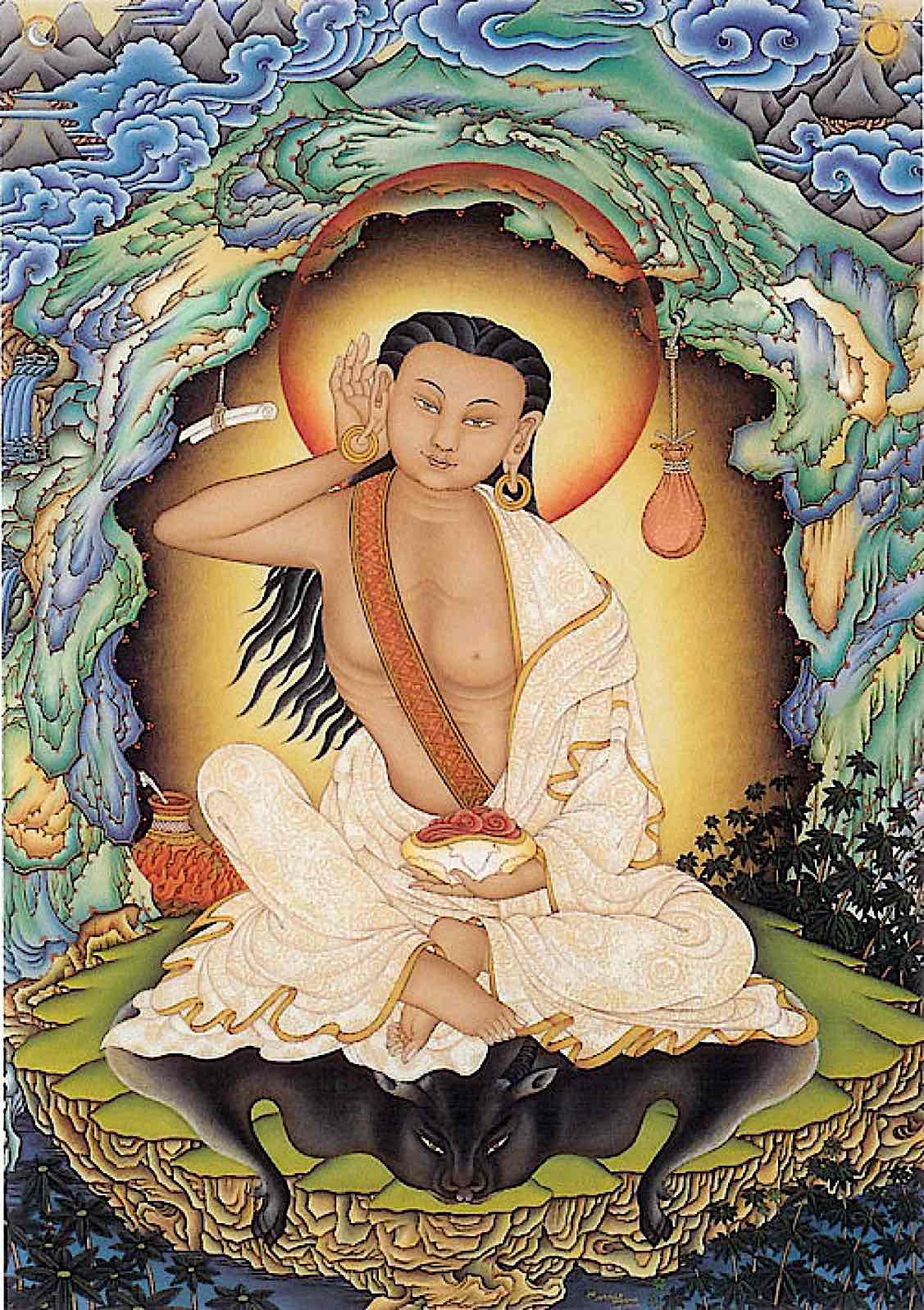

Milarepa was one of the greatest sages of Tibet, a hermit who achieved Enlightenment in his lifetime — but he began life with poor choices that resulted in the deaths of many. He may have started his great life chasing the stick, but he ended up facing the lion.

The Lion’s Gaze: for spiritual progress, personal life, business, sports, politics

Padmasambhava and Milarepa’s advice cuts across the centuries, and also the cultural divides we erect between religion, personal growth, business and politics. By that I mean, this pure gold nugget of advice is beneficial regardless of context.

Instead of chasing the stick, we can learn to focus on the lion in our office (business), or in the news (politics), or in stressful day-to-day life. Avoiding the distraction, the temptation to chase that stick, is a wonderful guiding principle in many situations.

Milarepa, of course, was focused on spiritual progress and the path to realisations — but The Lion’s Gaze should be metaphorically framed on the wall of corporate headquarters, government offices and prominently in the home.

With so many modern distractions — and remembering the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path — it’s easy to see how Milarepa’s pointed Lion parable is, perhaps, more relevant today than hundreds of years ago when he spoke those words.

Pema Choe-Dron likened the parable to Dzogchen:

“A ripened continuous insight gives us the steadiness and courage of a lion’s gaze. Padmasambhava said that when a stick is thrown to a lion, the lion gazes steadily at the source, the thrower. A dog’s gaze follows the object, the stick. Similarly, our source of experience is our own mind. The stick is only the phenomena. We need to look at our mind, the source of the emotion. An emotion like anger represents the stick. The source hurling that emotion is our mind. It is mind that projects. A wise and clear mind experiences something far more luminous and transparent. Conduct is caring. Such dynamic inner and outer relationship informs and purifies our vision. Dzogchen turns our gaze inward toward the source of experience, which is mind. Our own irrefutable experience is “certainty wisdom”. Buddhists also call this vajra pride. Vajra pride is not ego mind, but an indestructible diamond luminous wisdom view (vajra). Pristine mind is our lion’s gaze. This view is dzogchen.”

Lion’s Gaze parable

The Lion’s Gaze parable is first attributed (I believe) to Padmasambhava, as explained by T. Dogyal and P. Sherab in “The Lion’s Gaze”:

A ripened continuous insight gives us the steadiness and courage of a lion’s gaze.

Padmasambhava said that when a stick is thrown to a dog, the dog will chase the stick. When you throw a stick to a lion, the lion will chase you. The lion gazes steadily at the source, the thrower. A dog’s gaze follows the object, the stick. Similarly, our source of experience is our own mind. … An emotion, like anger, represents the stick.

The source hurling that emotion is our mind. It is the mind that projects. … a mind functioning beyond the jumbling of discursive emotions develops a steady and awake inner gaze, piercing the welter of thoughts. [7]

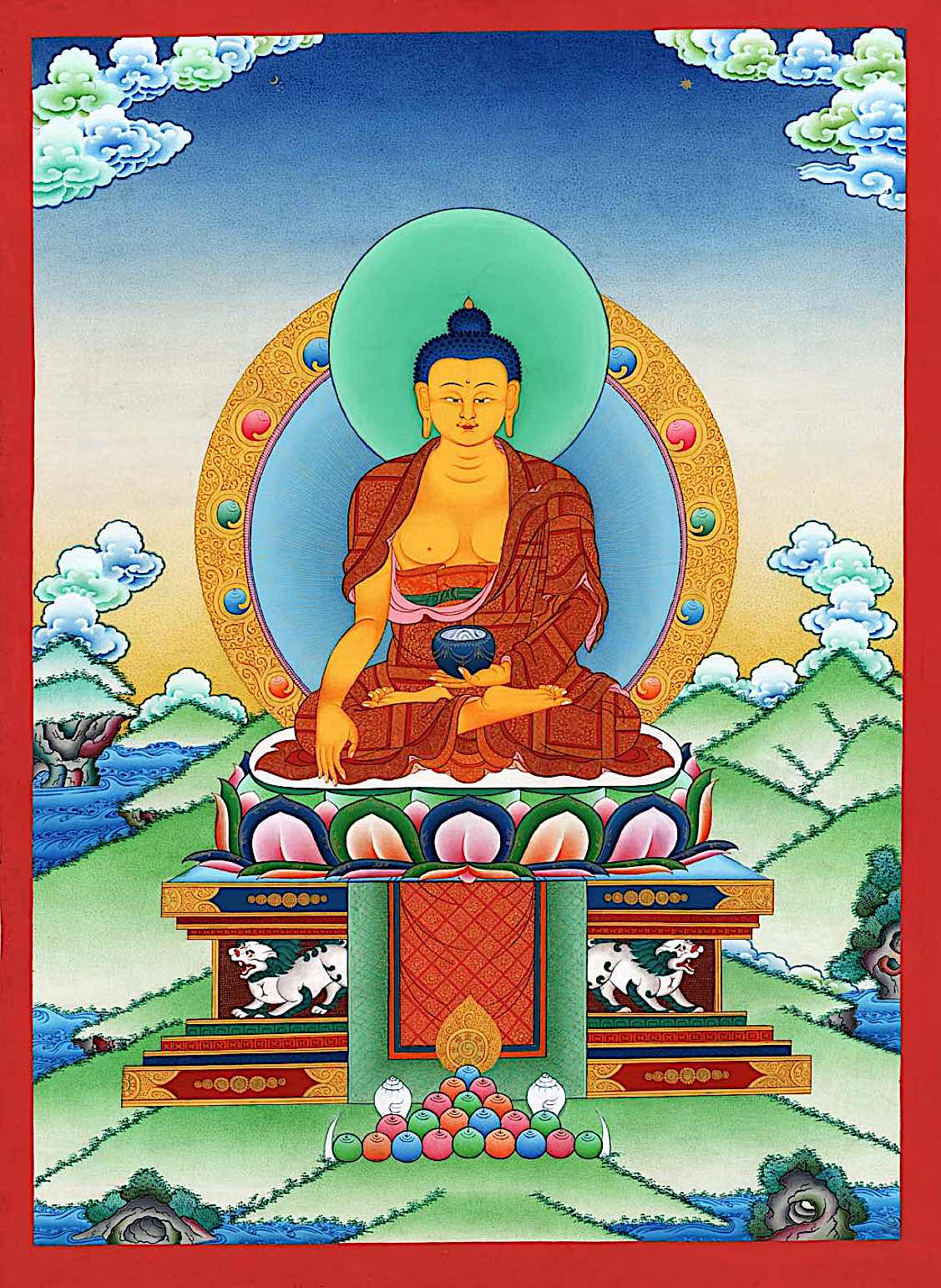

No matter how many times the parable is retold, the wisdom remains timeless. The great Yogi Milarepa, like Padmasambhava and Shakyamuni Buddha before him, could deliver world-changing advice in one or two sentences — the metaphorical roar of the lion. “The Lion’s Roar” is a frequent metaphor for the “Awakening Dharma” of the Buddha.[5]

Dogen wrote:

“When Sakyamuni Buddha was born, he pointed one hand to heaven and one hand to earth and said with a lion’s roar: I alone am the honored one in the heavens and on the earth.” The lion’s roar became synonymous with the Dharma. [6]

Lions, oh my! — The Lion’s Roar

Milarepa, the great Buddhist sage, echoed the lion-like wisdom of Shakyamuni Buddha. Long before images of Buddha finally appeared — in the first centuries after Buddha’s paranirvana there were no images or statues of Buddha; the lion was one of the representative symbols of Buddha (together with iconic symbols such as the footprints of the Buddha.). Lions also, later, became symbolic of bodhisattvas — the spiritual sons of the Buddha — often just called “Buddha’s lions.” [4]

Sariputta, one of Buddha’s chief followers, was described by Buddha as having speech like a “lion’s roar” in the Maha-parinibba Sutta: [2]

“Lofty indeed is this speech of yours, Sariputta, and lordly! A bold utterance, a veritable sounding of the lion’s roar!”

The lion is, of course, a recurring theme in Buddhism — and not only Buddhism but countless ancient traditions, including Egyptian myth, Hinduism and Chinese symbolism. What does it truly stand for, in terms of Jungian archetypes? The lion stands for “Self as it was meant to be, the ruler of the psyche.” [3]

We get more than a strong sense of this in Milarepa’s teaching: ” Instead, be like a lion who, rather than chasing after the stick, turns to face the thrower. One only throws a stick at a lion once.” Milarepa was coaching us to face the thrower — the self, the ego. (Of course, self in Buddhism, is contextually different from Western Jungian archetypes, but that’s a feature for another time.)

Lions in Buddhism: symbolizing the freedom and fearlessness of wisdom

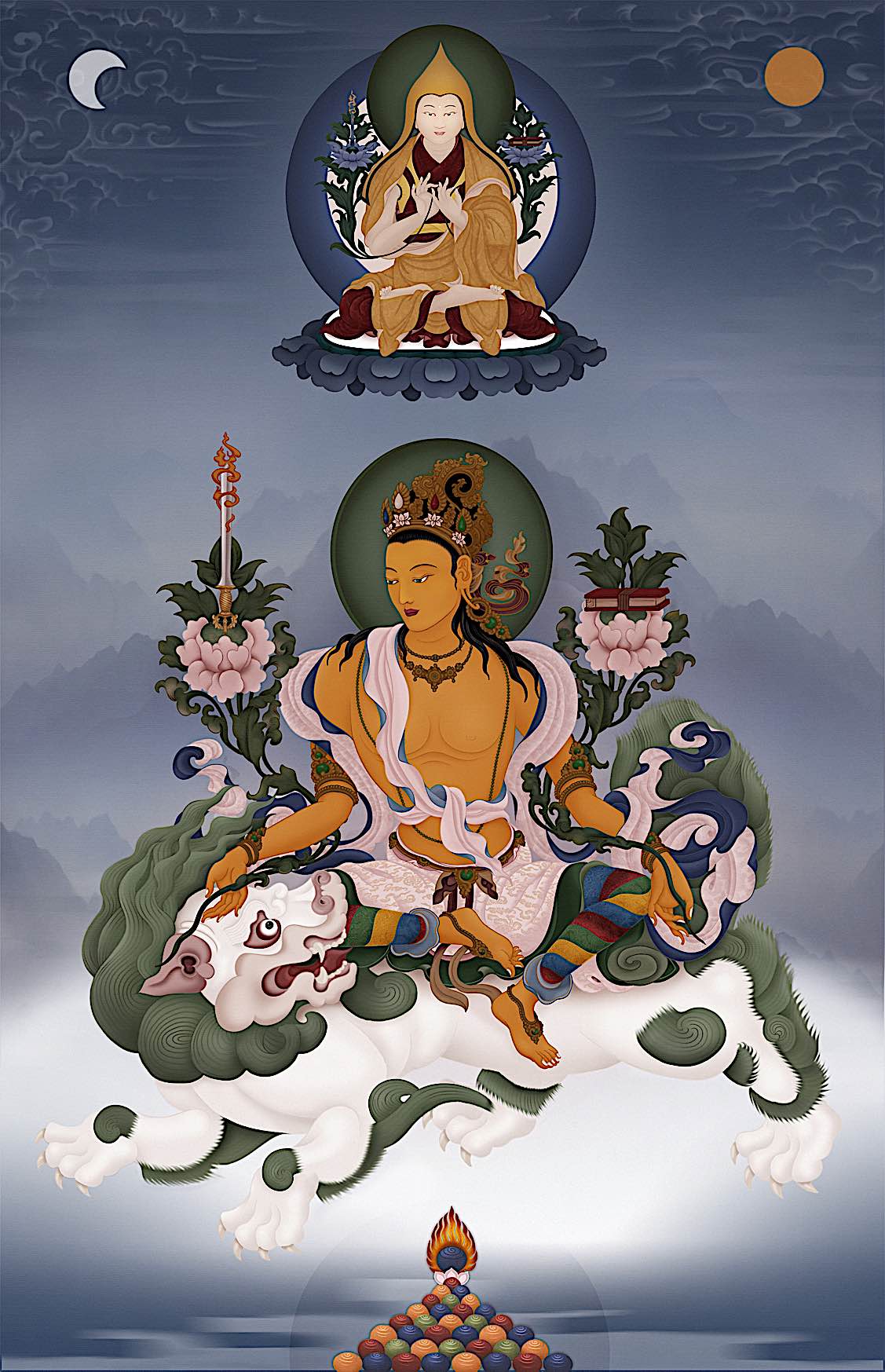

Buddha himself was represented by the lion. He was called “The Lion of the Shakya” (Shakya was his people or clan) — and he is frequently depicted sitting on a lion as a throne.

His speech was the “lion’s speech.” His spiritual sons (in Mahayana Buddhism) were “Buddha’s lions.” The symbol of the lion — and the snow lion especially — often appeared with Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. They are also found at temple entrances. What do they symbolize? According to Venerable Jampa Choskyi:

“They roam freely in the high snow mountains without any fear, symbolising the wisdom, fearlessness and divine pride of those dharma practitioners who are actually able to live freely in the high snow mountain of the pure mind, without being contaminated by delusions. They are kings of the doctrine because they have achieved the power to subdue all beings with their great love, compassion and wisdom.”

In Tibetan Buddhism, there is also the symbolism of the “Lion-face Dakini” — wisdom that “illuminates the darkest corners.” [5] In Chinese Buddhism there are not only snow lions, but also lion-dogs — Fu or Fo dogs, usually placed at entrances not only to temples but, also, important institutions.

The importance of the lion as a symbol and a parable continues today. If we can learn to “face the lion” instead of chasing the stick, we would be able to make progress in Buddhist practice.

NOTES

[1] Cited from “The Lion’s Gaze”

[2] Maha-parinibbana Sutta: DN 16

[3] Jungian Dreamwork Series: Animals: (Part II)

[4] “Symbolism of Animals in Buddhism, Ven Jampa Choskyi

[5] Lion Symbolism: Chinese Buddhist Encyclopedia.

[6] “How did lions become a symbol of Buddhism?” by Kathy McWilliams

2 thoughts on “The Lion’s Gaze and the Lion’s Roar: Padmasambhava, Milarepa and Buddha’s lion wisdom even more relevant in today’s hectic world”

Leave a Comment

More articles by this author

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Lee Kane

Author | Buddha Weekly

Lee Kane is the editor of Buddha Weekly, since 2007. His main focuses as a writer are mindfulness techniques, meditation, Dharma and Sutra commentaries, Buddhist practices, international perspectives and traditions, Vajrayana, Mahayana, Zen. He also covers various events.

Lee also contributes as a writer to various other online magazines and blogs.

If there is someone actually attacking you, what does the Lion do, then? Allow that person to attack them and leave?

I’m confused about what is supposed to be done when one is actually wronged by someone else.

It seems that the deities, with their wrathful forms, take action. What do we do?

Dear Athos, there is no one answer — and the lion here isn’t really referring to anger. Guru Padmasambhava was comparing the mind that chases the stick like a dog, versus the mind that resolutely turns to face the lion. (Today, we might think of the busy office worker, trying to put out five fires at once in the office, but instead of busily putting out five fires at one, should instead turn to the one who is starting those fires — the cause.) So, this was a parable about mind and distracted mind and mindfulness.

Having said that, Buddha taught ways to overcome anger (which can generate from a situation where someone wronged you) — anger self-perpetuates. There are the Five Buddhas (one for each poison. For Anger, the Buddha is Akshobya, who transforms Anger into “mirror-like Wisdom.)

Staying with the lion metaphor, there’s a difference between a lion defending herself, and a lion seeking vengeance (not the best metaphor here, but since we’re on the lion theme.) In nature, though, a lion would not seek vengeance or perpetuate the anger — she would defend, then move on.

When someone wrongs us, our pride (which is a poison in Buddhism), is hurt and we feel the urge to strike back. But, the methods Buddha taught, help us keep that “poison” under control. By being mindful, we can stop ourselves and observe our own mind in the present moment. Observe our anger. See it rise up and rage, but don’t act on it — only observe. See how silly it is to give in and become part of the problem. In the case of humans, where anger can be like a forest fire — out-of-control, if we let it — we can learn to work with our anger. (Buddha did use the metaphor of the forest fire to illustrate human anger.)

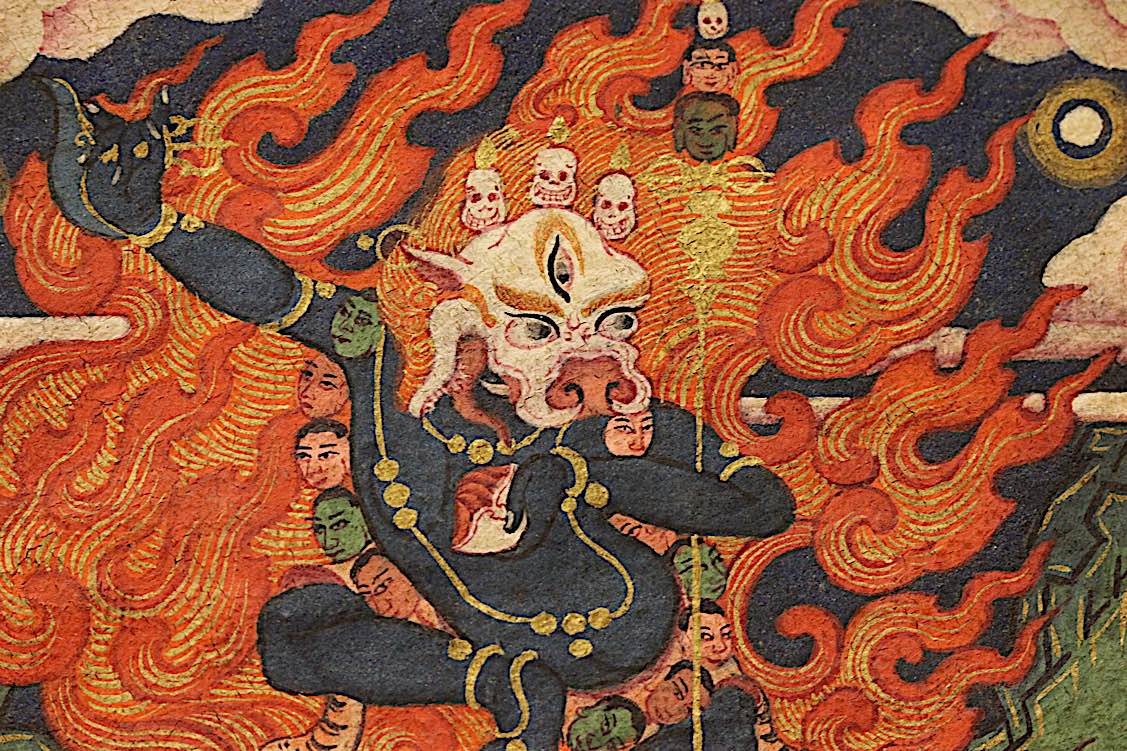

You mentioned wrathful deities — but this is a very advanced practice and the wrath is not literal — it’s symbolizes turning the power of wrathful emotion into something constructive. Wrathful deities, if we are initiated into their practice (not advised otherwise) act within our own minds, particularly.

Since wrathful deities are Enlightened deities there’s no thought of payback on someone who wronged us. It is more like: how to turn this into a constructive practice moment, to allow our own Enlightened qualities to emerge. So, yes, wrathful deities take action, but in the domain of our own minds. Yamantaka, for example, is a wrathful deity who transforms our anger from a poison into a Wisdom. That’s the literal language — transforming a “poison” into a “Wisdom.” This happens within our minds. We’re not taking action against an external force. We are taking this anger, which is obviously a powerful force, and transforming it into a moment for clarity and wisdom. There are some other stories in BW about wrathful deities, hope they’re helpful, but the main thing is to transform — rather than control. Turn the force of anger into wisdom. Metta, Lee