Painter and digital Thangka artist Jampay Dorje aims to bring “Thangka painting into a modern era” with spectacular art, lessons for students, and a life-long project to illustrate all of the 11 Yogas of Naropa

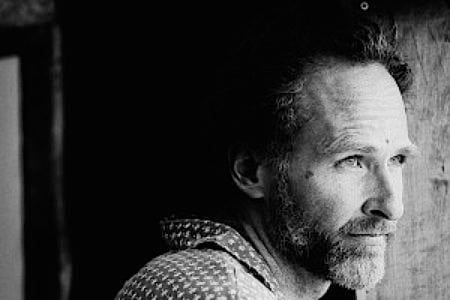

Jampay Dorje, also known as Ben Christian, has a mission in life. Dividing his time between retreat, teaching digital art, and creating Thangkas for Buddhist practitioners, he has become well known on the internet for his spectacular images.

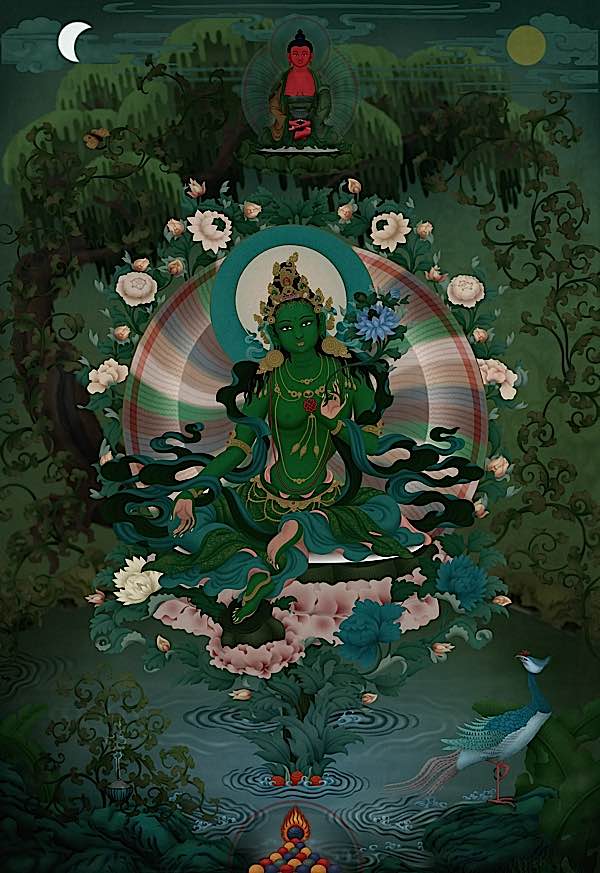

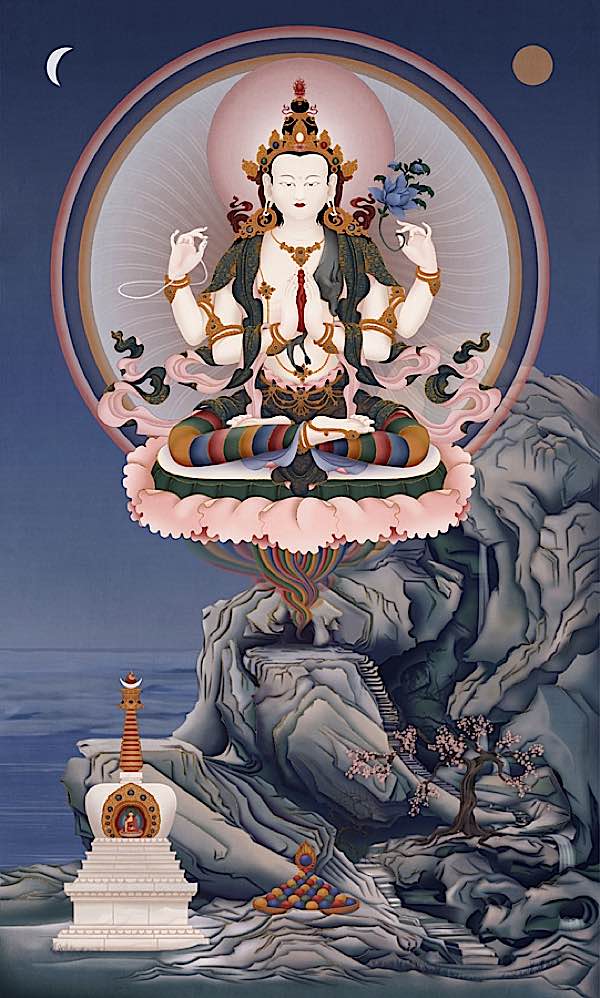

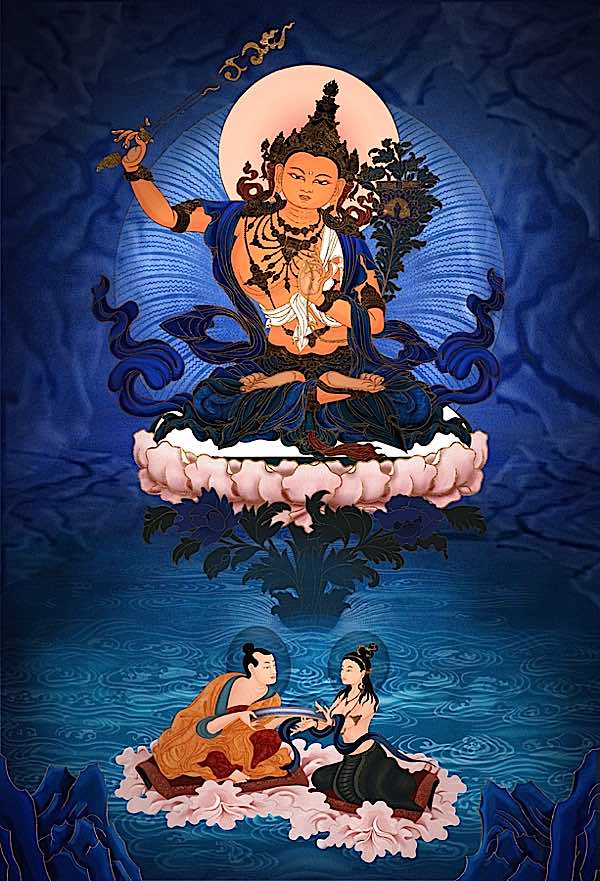

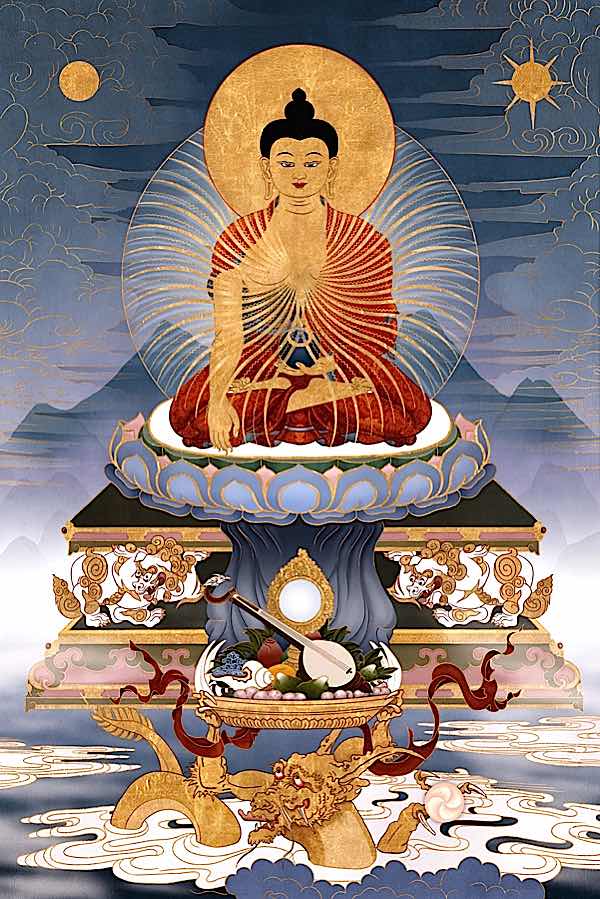

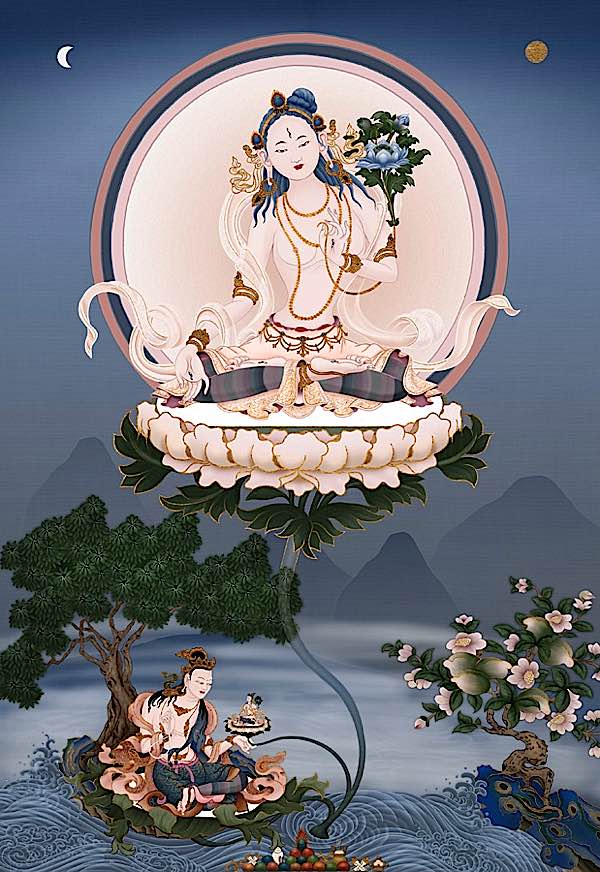

Beautiful thangka images kept appearing to me (several included in this feature), without watermarks, on the internet, usually without credits. On a mission myself, I sought out the creative artist behind this artwork I saw almost daily on my Facebook feed.

I was destined for both an exciting encounter, and disappointment. My disappointment was that he could not take a commission from me to illustrate my Yidam — which was my selfish goal. My excitement, however, built as he explained the reason why; he was committed to a life-mission to illustrate fully the entire 11 Yogas of Naropa — the entire practice of Vajrayogini. As he explained in the interview:

Speaking very generally, if we were to antidote the three primary afflictions — ignorance, attachment and aversion — then samsara would cease to exist for us. The most powerful antidote to those three is to be found in Tantra. There is a specific tantra that is most suitable to each of us, and this is what it means to find our yidam. For those who have found their yidam in Vajrayogini, I am here to serve you.

To my knowledge, there is only one thangka (historically) that attempted illustrating the entire 11 Yogas. Jampay Dorje aims to create multiple tangkhas, which, when juxtapositioned side-by-side, create a massive mural illustrating the entire creation and completion stages of this Highest Yoga practice.

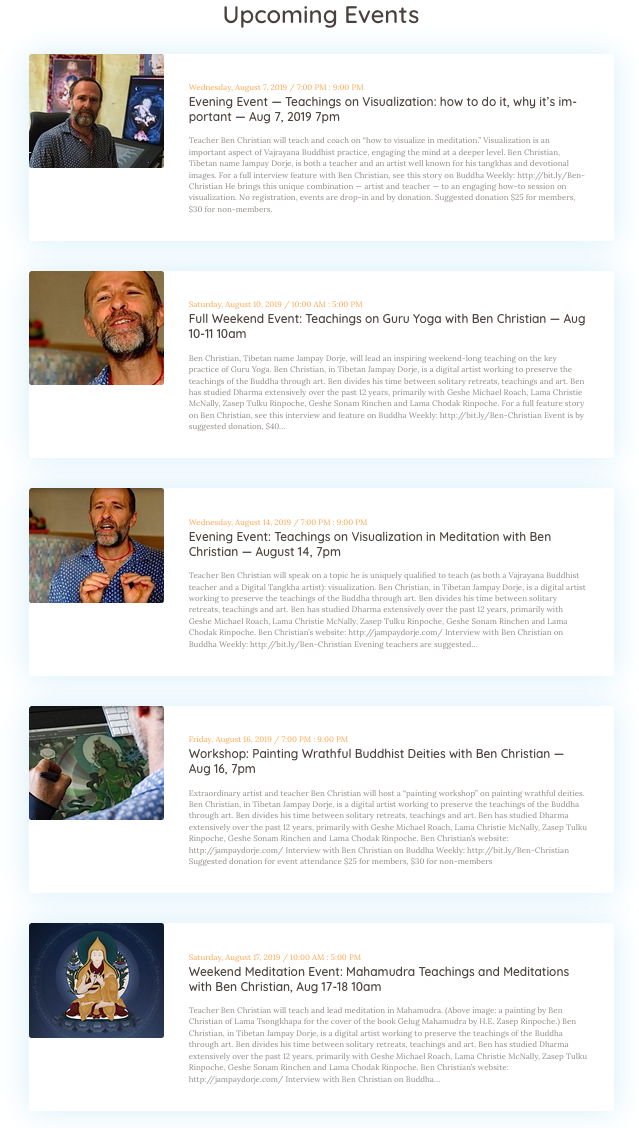

Captivated by this ambitious decades-long mission, I asked for an interview. As the interview unfolded, I learned that he also spends some time training new digital thanka artists (one of his how-to videos, “how to paint a dragon” embedded below). He also makes his past images of Tara, Manjushri and other Buddhas freely available on his website, and available as high-quality prints. He is supported in his bigger mission, the 11 Yogas of Naropa project by patrons via the Patreon site (Please visit this site and see if you can help out!>>)

May all beings benefit from his work. [Important links to Jampay Dorje’s work, bio, downloads and prints at end of this feature.]

BW: Please tell us about your past work and your goals for that work.

It’s a long story but I think I began in around 2008. At that time I was studying Dharma in the US and we had just begun to meditate on the Dzogrim practices. Something changed in me during that time, I remember flying back home to Australia and being consumed by the images of the subtle body. On the plane I opened my laptop and began illustrating what I saw in my mind. At that time I was unable to ‘paint’ on a computer, so the early images were very digital in appearance. The digital look didn’t bother me too much as the inner body lends itself to that kind of imagery. Later I would spend many years developing the techniques to remove that ‘ digital look.’ Over subsequent years I taught myself to paint on a computer, and the first major work I undertook was to completely illustrate a very beautiful Dzogrim text by Tuken Dharma Vajra.

It’s a long story but I think I began in around 2008. At that time I was studying Dharma in the US and we had just begun to meditate on the Dzogrim practices. Something changed in me during that time, I remember flying back home to Australia and being consumed by the images of the subtle body. On the plane I opened my laptop and began illustrating what I saw in my mind. At that time I was unable to ‘paint’ on a computer, so the early images were very digital in appearance. The digital look didn’t bother me too much as the inner body lends itself to that kind of imagery. Later I would spend many years developing the techniques to remove that ‘ digital look.’ Over subsequent years I taught myself to paint on a computer, and the first major work I undertook was to completely illustrate a very beautiful Dzogrim text by Tuken Dharma Vajra.

It was a difficult time for me, but I very much wanted to complete the work perfectly and offer it to my Lama and Sangha as a way to collect the karma to become a great artist in the Tibetan tradition. .

From there I went on to do many illustrations to illuminate the material we were studying. By around 2010 I had developed the techniques to be able to complete my first thangka. I subsequently went into a five-year period where I did only meditation retreat and art. I would do between 4-8 weeks of retreat; take a month or two break to complete a thangka, and then go back into retreat. This was an amazing time for me. I did so much retreat and art, and they worked perfectly together. Each retreat I was well-rested and fresh – and completely loaded with wonderful karma from my time spent painting during the breaks. During that period I created around twelve works which I used to raise money for the Asian Classics Input Project.

BW: You mentioned that your goal is to “bring Thagka painting into a modern era” and you strive to preserve the spiritual integrity while “introducing modern techniques for the people who are attracted to painting that way.” Can you elaborate on that a bit?

In everyday life, we often hear the saying ‘change is inevitable.’ I think sometimes when people say this there is an idea of a kind of stasis that is occasionally interrupted by change. From the Buddhist perspective the vast majority of all things are subject to change; not at some time in the future but from hour to hour and moment to moment, right now. The tradition of thangka painting is subject to this change as much as anything else. I think that change can be further divided into three: change that is favourable, change that is neutral, and change that is unfavourable. Digital painting is a radical departure from traditional painting. So in my mind, it is important to identify the ways that this departure benefits or harms the tradition and create our work accordingly.

Thangka painting is the activity of a bodhisattva. It is the Perfection of Giving. More specifically it is the Perfection of Giving Dharma. So the art is all about serving others in a very unique and holy way. For our digital art to be the activity of a bodhisattva, it needs to be very respectful of the existing tradition and not undermine it in any way. As artists, we should build on this tradition by understanding every aspect of the iconography, not just the symbols themselves, but the underlying dharma realisations that these symbols represent. Then we have a chance of painting dharma and not just pictures. There are so many reasons why we need to preserve the tradition.

Working digitally has many benefits. As a work method, it is efficient, speedy and editable. Even if someone were a very accomplished artist they may not be able to paint thangkas due to the extreme precision of line work required. They may have poor eyesight or simply lack the endurance to paint in that way. Digital painting solves all those problems and makes thangka painting accessible to everybody.

You can draw and erase a line an unlimited number of times without harming the image. You can zoom into areas of fine detail. Painting a sky gradient may take a month traditionally, it can be completed in a few minutes digitally. I think many people would like to try to paint the divine, to record or express what they see. It’s a natural reaction to encountering it. Digital painting makes that available to almost everyone, and it’s a virtue. The bottom line for me is love for others and serving them through art; so for me a digital workflow makes the most sense since I am able to produce the most work this way.

There will be a future generation of Tibetan, Mongolian, Bhutanese and Western thangka artists who will have been using computers since childhood and who will step into digital art as easily as writing on a piece of paper. I want to use my time developing the techniques to serve these future artists, as well as navigating all the spiritual and motivational issues that these artists will need to face. That way I feel like I can cultivate the correct form of change and avoid the negative aspects of change.

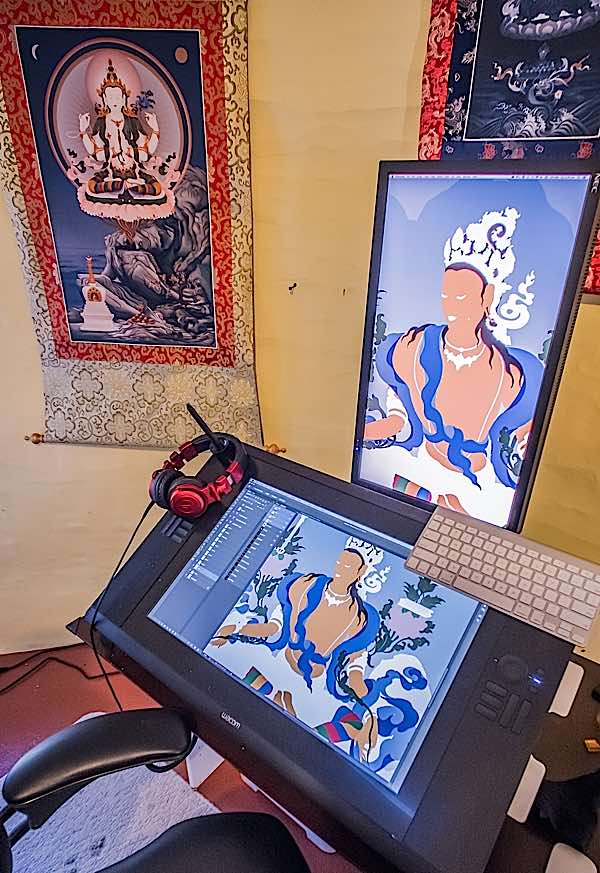

BW: For those of our readers who are artistically inclined, can you describe how you work in the creation of the images?

It’s actually very easy, I feel like I can teach anyone who has an interest to paint thangkas whether they are artistic or not. There is a wonderful crossover between the workflow of the traditional thangka artist, the digital thangka artist and the digital cartoonist. They all share the same methodology of creating an outline, flat colouring then shading. I actually learned to paint thangkas by watching DVD tutorials of modern cartoon artists. So basically you create a sketch, evolve that sketch into a finished line, colour between the lines, and then apply shading to create the illusion of volume.

I work primarily in Photoshop. Its most powerful feature is that you can paint on unlimited transparent layers; so you can easily change individual aspects of the image without needing to repaint. I paint using a Wacom pressure sensitive tablet. It is like drawing on a computer screen – with a pen that is sensitive to pressure, tilt, opacity etc – just as a normal paint brush would be. Each painting takes about 200-300 hours to complete. If anyone is interested there is a tutorial here showing the process. (Video embedded here.)

BW: Please tell us about your lifetime commitment to the 11 Yogas of Naropa (Vajrayogini) Project? Why is this important to you? What gave you the idea in the first place?

I mentioned before that I consider thangka painting to be the activity of a Bodhisattva. Whilst I can’t say that I have made much progress as a Bodhisattva, I do feel immensely attracted to developing that heart and mind along with trying to emulate the activities of those great Beings. Lord Maitreya defines bodhicitta as ‘The desire to become enlightened for the benefit of others.’ To offer the mechanism to reach enlightenment to another person is the greatest gift one could ever give. We can’t give someone enlightenment because we can’t give our realisations to another; even Lord Buddha was unable to do this. We can, however, take a single individual — and with deep insight into their personality — provide for them all the conditions necessary for their own journey to enlightenment. I personally have no particular insight into what another person needs spiritually. There have, however, been beings in the past who have possessed this insight; and they have identified consistent and fundamental flaws in our heart and mind which create our own version of samsara.

Each sentient being within samsara remains locked in this prison due to their fundamental ignorance of the ultimate nature of reality and from that ignorance spring the two “henchmen” of attachment and aversion.

Speaking very generally, if we were to antidote the three primary afflictions —ignorance, attachment and aversion — then samsara would cease to exist for us. The most powerful antidote to those three is to be found in Tantra. There is a specific tantra that is most suitable to each of us, and this is what it means to find our yidam. For those who have found their yidam in Vajrayogini, I am here to serve you.

If we were to take the tantra of Vajrayogini as our path to enlightenment then we would traverse the stages of both creation and completion. The Eleven Yogas of Naropa constitute the Creation Stage, and the Six Yogas of Naropa constitute the Completion Stage. The eleven and the six yogas are immaculately presented and documented in both the Tibetan and Western commentaries; they are rich and wonderful practices, beyond words. The doorway to each of these yogas is a visualisation; it’s a described mental image that the meditator uses to build their realisations of the path, the way it works is profound…

In an offhand way, someone once said to me “it would be good if you illustrated the 11 Yogas so people know what to visualise.” If it is possible to reach a permanent end to suffering, where we can reach the immaculate body of a Buddha, then wouldn’t this be the perfect gift to give to another. If that gift can’t be given then at least it should be facilitated. If Tantra is the only doorway to enlightenment, then to facilitate the practice of the few and rare individuals who practice it sincerely must be the highest thing. So that why I paint the 11 Yogas. If my mother were still alive it is what I would give to her.

BW: You mentioned it could take many years to complete the entire 11 Yogas of Naropa Vajrayogini project. What motivated you to take on such an ambitious project? Why is it so important to you?

I think each of us who practice Tantra sincerely have a deep relationship with our yidam: there is an ongoing narrative, and this is mine. It’s quite personal and reaches across lifetimes…it’s hard to discuss. I do feel that I began this project in a past life and perhaps felt sad that I couldn’t do it justice, that there simply wasn’t time. I feel that I made a sincere prayer at that time that I would be reborn in a place and time where I had the resources necessary to complete this project. I feel like that time is now. As an artist I can look to the sky and see exactly what I will paint: it’s beautiful…and I have no doubt that it will serve all practitioners of Vajrayogini for a very long time. When I see in this way it is impossible to step away…to see something so beautiful in your mind, to be able to paint the holy body of a Buddha and the path to reach that body and then to step away is unthinkable.

BW: You said, on Patreon, that a conventional artist might take three lifetimes to finish a project of this scope. How will digital technology help you accomplish this in 15 or so years?

The actual painting of the Eleven Yogas is huge, it will be about 6m long and 1m high, it will be composed of 9 individual panels with over 30 individual scenes and around 150 deities. It really comes down to efficiency. I just finished painting Guhyasmaja, for example, and there are two instances where I intend to use Guhyasamaja in the image (in the refuge/merit field; and the torma offering; so yogas number four and eleven). Working digitally I only need to paint the deity once. From there I can easily composite the deity into any scene that they are needed. The ability to do that saves about 200 hours of work and that time saving is present in almost every instance of the thangka. It adds up.

Jampay Dorje speaks about the 11 Yogas of Naropa Vajrayogini project and how to be a patron:

BW: You characterized the 11 Yogas, in your view, as a complete and supreme path. Why do you feel this way?

I want to preface this by saying that my only experience is in the Gelugpa system and specifically as it was passed to them from the great Sakya masters of Vajrayogini. I think that many times we might have a particular practice to which we are attracted, but if we look closely within that practice the exact path to enlightenment may not be all that clear.

On a purely pragmatic level, I believe the Vajrayogini system to be absolutely complete. In the Gelugpa system, we have the immaculate works of Ngulchu Dharmabhadra and Dechen Nyingpo and the contemporary commentaries that have inspired from Geshe Lobsang Tarchin, Gelek Rinpoche and Geshe Loden. Each of these commentaries is extremely detailed and comprehensive. I believe that for Westerners the Vajrayogini system offers us the greatest available resources.

There are so many questions that arise for practitioners of Tantra. If these questions are left unanswered then they lead to conscious or unconscious doubt. Doubt has been spoken of as the core mental affliction that undermines tantra. If a path is comprehensive and clearly illuminated then it becomes traversable.

Having said all of that, the only thing that really matters is our relationship with our Lama! The mind and the world are empty of working in and of themselves; if we have collected the right virtue through understanding this and relating correctly to our Lama, then the Lama can press into our hand the most mundane of objects, and it will act as a path to the goal, simply due to the power of our reasoned faith.

BW: You also mentioned that the 11 Yogas of Naropa and Vajrayogini practices are very well documented with extensive, precise commentaries, and many teachers presenting the teachings. Do you view the image-project as a meditative aid to practitioners, an inspiration for non-practitioners, or as a spiritual practice for you and your team (or all of the above, but give us a sense of the main aspiration)?

It’s all three, and that is what makes it so wonderful! It is good for everybody it touches, on all levels.

BW: What’s the progress on the project. How many works per year can you manage on this ambitious project?

It’s hard to know exactly where I am on the project since I don’t work in a linear fashion. If painting traditionally you would be working your way through each of the images step-by-step; and once you started you would be committed to certain choices of colour and composition. The workflow I have adopted takes greatest advantage of the digital process. Stage one is to paint each of the individual deities and lamas, lotus cushions, stupas, trees, flowers, offerings etc, all of the individual components that will tell the overall story. I am about a quarter of the way through this process.

From there these individual elements will be composited to illustrate each of the Eleven Yogas within the overall landscape of the Burial Grounds surrounding the Mandala. The whole image is like a large panorama comprised of nine panels with eight panels dedicated to the Eleven Yogas: and the ninth panel is a commentary on what has been drawn. The burial ground will form the lower landscape element in each panel and the Yogas will fill the air above the landscape. This compositing of the image will occur in the final three years of the project when I hope to be at the peak of my artistic abilities.

BW: Are you treating the project almost as you would a retreat?

That’s a great question – I like to spend at least four months of the year in retreat. I don’t usually do art during that time. When I leave retreat, I rest or do art. Whether in retreat, resting or doing art I am in my Mandala, its all the same thing really, it’s simple and I am thankful for that simplicity. I only do one tantric practice along with mahamudra to support that practice. The final goal is to use these years well, to accumulate masses of good karma and at the conclusion of the Eleven Yogas Project to go into three year retreat and reach my goals.

BW: You are supporting the project with patron contributions on Patreon. Can you explain how you’ve set it up (and why).

Patreon is a website dedicated to finding funding for artists. It works by taking small pledges (on either a monthly or per work basis) in exchange for exclusive access to the artist’s work. I really like this system as I don’t like asking for money for my work; but I also recognise that it is inappropriate for it to be given away independent of some form of exchange. That exchange could occur through words, gesture or money. I don’t mind which method arises, but an exchange does needs to occur. This is particularly important for the tantric works.

If I show someone a print I can tell simply by the way they stand or hold the print whether that exchange has taken place… If it has then I am happy to give the print for free, if it hasn’t then it is better to put the print back in the box. When things are offered online that process is difficult to read, so a financial exchange is there in its place. At least it indicates the person’s respect for the work on some level, if this doesn’t happen then the karma is all wrong, it hurts the person and it hurts me.

So Patreon facilitates this exchange process for me and I am really happy with it. Last month I was able to pay my friend to do some calligraphy for one of my paintings: I was so happy as normally I would need to ask him to do it for free. With the money I receive from Patreon I am able to live a lifestyle where I can focus exclusively on my art and retreat. I feel very fortunate for this and hope that everyone who sends me money through patron feels as though the art I offer in exchange is perfect in every way.

BW: Just to clarify for our readers, you are not accepting commissions for work as you focus on the important 11 Yogas Project.

That is correct, unfortunately, I can’t paint everything in this life, I wish I could but there is not enough time, so generally, I don’t accept commissions. I do paint for my Lamas if requested but that is different. Very occasionally I will take a commission if it is part of the work for The Eleven Yogas Project.

Important Links

Become a patron of the 11 Yogas of Naropa project>>

More extensive biography of Jampay Dorje>>

Jampay Dorje’s prints as high resolution at Fine Art America>>

Available Jampay Dorje downloads>>

6 thoughts on “Painter and digital Thangka artist Jampay Dorje aims to bring “Thangka painting into a modern era” with spectacular art, lessons for students, and a life-long project to illustrate all of the 11 Yogas of Naropa”

Leave a Comment

More articles by this author

Guru Rinpoche is ready to answer and grant wishes: “Repeat this prayer continuously” for the granting of wishes

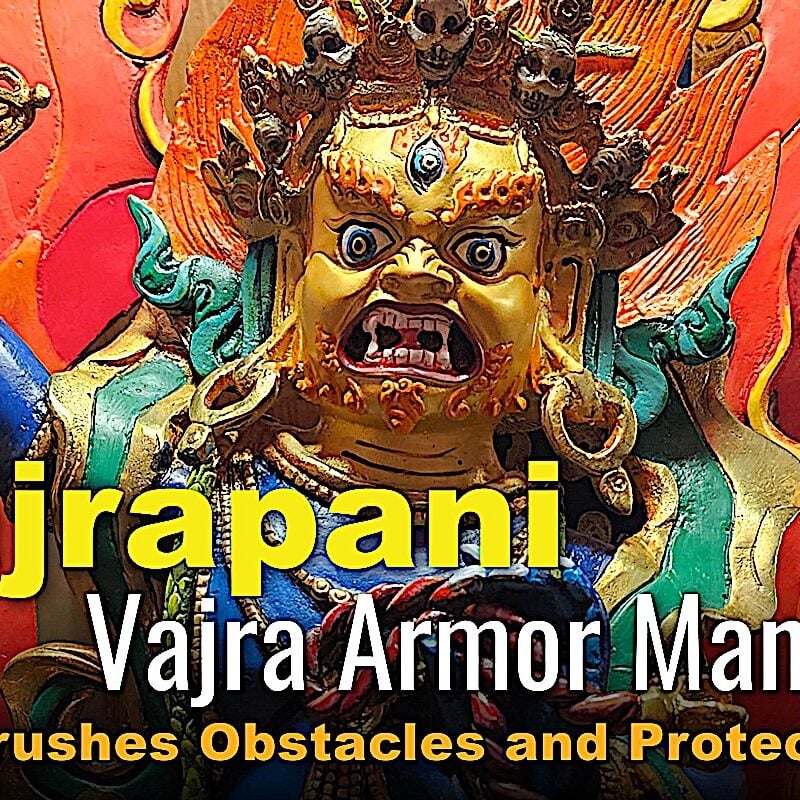

VIDEO: Vajrapani Vajra Armor Mantra: Supreme Protection of Dorje Godrab Vajrakavaca from Padmasambhava

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Lee Kane

Author | Buddha Weekly

Lee Kane is the editor of Buddha Weekly, since 2007. His main focuses as a writer are mindfulness techniques, meditation, Dharma and Sutra commentaries, Buddhist practices, international perspectives and traditions, Vajrayana, Mahayana, Zen. He also covers various events.

Lee also contributes as a writer to various other online magazines and blogs.

Your work never ceases to inspire my own path Ben, and graces my gompa. Thank you. This is a great article, ill share it. And as many others do Im sure, will continue to follow your progress with the 11 Yogas of Naropa project. I was one of those who originally traced you after seeing and sharing your beautiful Vajradhara, who glances down on my practice from the wall while i practice. Thank you.

Thankyou Noelene, I am happy as always to support you and others through my art. Love to you, Ben (Jampay Dorje)

Beautiful work, good intent, attention to detail, impressive concern!

Tara is my saviour

You’re really gifted Jampay Dorje, your painstakenly work are reflected in each of the master piece posted in the Internet. It is my sincere wish that you obtained enlightenment ASAP, coz drawing pictures of Buddahs, Bodhisattvas, Yogas and the likes gives you tremendously great merits, so your path to freedom from this samsara the evil turning wheel of suffering will no longer bind you.

Thankyou Teng for your kind words. I hope to bring you many more images over the coming years. Best wishes to you, Ben (Jampay Dorje)

Amazing.

As artists would love to learn how to use modern technology. It would be amazing for us to have someone with such talent to teach in our thangka art school. Hopefully one day 🙂

Congratulations to Jampay Dorje for the dedication and passion and thank you to the author for the very interesting post.

Namaste.