Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Sutta: The Great Discourse on the Establishing of Awareness; mindfulness of body, feelings, mind, mental qualities

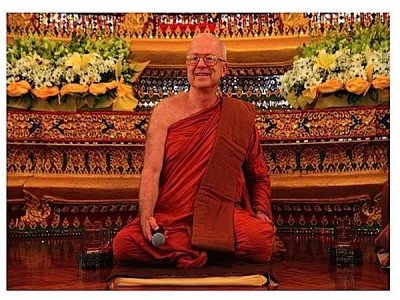

Thanissaro Bhikkhu, who translated the sutra below, cautioned in his commentary:

At first glance, the four frames of reference for satipatthana practice sound like four different meditation exercises, but MN 118 makes clear that they can all center on a single practice: keeping the breath in mind. When the mind is with the breath, all four frames of reference are right there.

These four mindfulnesses are an important teaching in Tibetan Mahamudra. Normally, the teacher begins with instructions in meditation on breath and “mindfulness.” Then, often the teacher, especially on a retreat, will separately guide meditations on the four mindfulnesses: body, feelings, mind, mental qualities. In part 2 of Buddha Weekly’s coverage of a weekend Mahamudra event, Venerable Zasep Tulku Rinpoche said:

“You should refer to the Mahasatipatthana Sutta, the Great Mindfulness Sutta, which taught how to establish mindfulness of body (Kaya), sensations (Vedana), mind (Citta) and mental contents (Dhamma).”

Maha-satipatthana Sutta: The Great Frames of Reference

translated from the Pali by

Thanissaro Bhikkhu

I have heard that on one occasion the Blessed One was staying in the Kuru country. Now there is a town of the Kurus called Kammasadhamma. There the Blessed One addressed the monks, “Monks.”

“Lord,” the monks replied.

The Blessed One said this: “This is the direct path for the purification of beings, for the overcoming of sorrow & lamentation, for the disappearance of pain & distress, for the attainment of the right method, & for the realization of Unbinding — in other words, the four frames of reference. Which four?

“There is the case where a monk remains focused on the body in & of itself — ardent, alert, & mindful — putting aside greed & distress with reference to the world. He remains focused on feelings… mind… mental qualities in & of themselves — ardent, alert, & mindful — putting aside greed & distress with reference to the world.

A. Body

“And how does a monk remain focused on the body in & of itself?

[1] “There is the case where a monk — having gone to the wilderness, to the shade of a tree, or to an empty building — sits down folding his legs crosswise, holding his body erect and setting mindfulness to the fore [lit: the front of the chest]. Always mindful, he breathes in; mindful he breathes out.

“Breathing in long, he discerns, ‘I am breathing in long’; or breathing out long, he discerns, ‘I am breathing out long.’ Or breathing in short, he discerns, ‘I am breathing in short’; or breathing out short, he discerns, ‘I am breathing out short.’ He trains himself, ‘I will breathe in sensitive to the entire body.’ He trains himself, ‘I will breathe out sensitive to the entire body.’ He trains himself, ‘I will breathe in calming bodily fabrication.’ He trains himself, ‘I will breathe out calming bodily fabrication.’ Just as a skilled turner or his apprentice, when making a long turn, discerns, ‘I am making a long turn,’ or when making a short turn discerns, ‘I am making a short turn’; in the same way the monk, when breathing in long, discerns, ‘I am breathing in long’; or breathing out long, he discerns, ‘I am breathing out long’ … He trains himself, ‘I will breathe in calming bodily fabrication.’ He trains himself, ‘I will breathe out calming bodily fabrication.’

“In this way he remains focused internally on the body in & of itself, or externally on the body in & of itself, or both internally & externally on the body in & of itself. Or he remains focused on the phenomenon of origination with regard to the body, on the phenomenon of passing away with regard to the body, or on the phenomenon of origination & passing away with regard to the body. Or his mindfulness that ‘There is a body’ is maintained to the extent of knowledge & remembrance. And he remains independent, unsustained by (not clinging to) anything in the world. This is how a monk remains focused on the body in & of itself.

[2] “Furthermore, when walking, the monk discerns, ‘I am walking.’ When standing, he discerns, ‘I am standing.’ When sitting, he discerns, ‘I am sitting.’ When lying down, he discerns, ‘I am lying down.’ Or however his body is disposed, that is how he discerns it.

“In this way he remains focused internally on the body in & of itself, or focused externally… unsustained by anything in the world. This is how a monk remains focused on the body in & of itself.

[3] “Furthermore, when going forward & returning, he makes himself fully alert; when looking toward & looking away… when bending & extending his limbs… when carrying his outer cloak, his upper robe & his bowl… when eating, drinking, chewing, & savoring… when urinating & defecating… when walking, standing, sitting, falling asleep, waking up, talking, & remaining silent, he makes himself fully alert.

“In this way he remains focused internally on the body in & of itself, or focused externally… unsustained by anything in the world. This is how a monk remains focused on the body in & of itself.

[4] “Furthermore… just as if a sack with openings at both ends were full of various kinds of grain — wheat, rice, mung beans, kidney beans, sesame seeds, husked rice — and a man with good eyesight, pouring it out, were to reflect, ‘This is wheat. This is rice. These are mung beans. These are kidney beans. These are sesame seeds. This is husked rice,’ in the same way, monks, a monk reflects on this very body from the soles of the feet on up, from the crown of the head on down, surrounded by skin and full of various kinds of unclean things: ‘In this body there are head hairs, body hairs, nails, teeth, skin, flesh, tendons, bones, bone marrow, kidneys, heart, liver, pleura, spleen, lungs, large intestines, small intestines, gorge, feces, bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, fat, tears, skin-oil, saliva, mucus, fluid in the joints, urine.’

“In this way he remains focused internally on the body in & of itself, or focused externally… unsustained by anything in the world. This is how a monk remains focused on the body in & of itself.

[5] “Furthermore… just as a skilled butcher or his apprentice, having killed a cow, would sit at a crossroads cutting it up into pieces, the monk contemplates this very body — however it stands, however it is disposed — in terms of properties: ‘In this body there is the earth property, the liquid property, the fire property, & the wind property.’

“In this way he remains focused internally on the body in & of itself, or focused externally… unsustained by anything in the world. This is how a monk remains focused on the body in & of itself.

[6] “Furthermore, as if he were to see a corpse cast away in a charnel ground — one day, two days, three days dead — bloated, livid, & festering, he applies it to this very body, ‘This body, too: Such is its nature, such is its future, such its unavoidable fate’…

“Or again, as if he were to see a corpse cast away in a charnel ground, picked at by crows, vultures, & hawks, by dogs, hyenas, & various other creatures… a skeleton smeared with flesh & blood, connected with tendons… a fleshless skeleton smeared with blood, connected with tendons… a skeleton without flesh or blood, connected with tendons… bones detached from their tendons, scattered in all directions — here a hand bone, there a foot bone, here a shin bone, there a thigh bone, here a hip bone, there a back bone, here a rib, there a breast bone, here a shoulder bone, there a neck bone, here a jaw bone, there a tooth, here a skull… the bones whitened, somewhat like the color of shells… piled up, more than a year old… decomposed into a powder: He applies it to this very body, ‘This body, too: Such is its nature, such is its future, such its unavoidable fate.’

“In this way he remains focused internally on the body in & of itself, or externally on the body in & of itself, or both internally & externally on the body in & of itself. Or he remains focused on the phenomenon of origination with regard to the body, on the phenomenon of passing away with regard to the body, or on the phenomenon of origination & passing away with regard to the body. Or his mindfulness that ‘There is a body’ is maintained to the extent of knowledge & remembrance. And he remains independent, unsustained by (not clinging to) anything in the world. This is how a monk remains focused on the body in & of itself.

(B. Feelings)

“And how does a monk remain focused on feelings in & of themselves? There is the case where a monk, when feeling a painful feeling, discerns, ‘I am feeling a painful feeling.’ When feeling a pleasant feeling, he discerns, ‘I am feeling a pleasant feeling.’ When feeling a neither-painful-nor-pleasant feeling, he discerns, ‘I am feeling a neither-painful-nor-pleasant feeling.’

“When feeling a painful feeling of the flesh, he discerns, ‘I am feeling a painful feeling of the flesh.’ When feeling a painful feeling not of the flesh, he discerns, ‘I am feeling a painful feeling not of the flesh.’ When feeling a pleasant feeling of the flesh, he discerns, ‘I am feeling a pleasant feeling of the flesh.’ When feeling a pleasant feeling not of the flesh, he discerns, ‘I am feeling a pleasant feeling not of the flesh.’ When feeling a neither-painful-nor-pleasant feeling of the flesh, he discerns, ‘I am feeling a neither-painful-nor-pleasant feeling of the flesh.’ When feeling a neither-painful-nor-pleasant feeling not of the flesh, he discerns, ‘I am feeling a neither-painful-nor-pleasant feeling not of the flesh.’

“In this way he remains focused internally on feelings in & of themselves, or externally on feelings in & of themselves, or both internally & externally on feelings in & of themselves. Or he remains focused on the phenomenon of origination with regard to feelings, on the phenomenon of passing away with regard to feelings, or on the phenomenon of origination & passing away with regard to feelings. Or his mindfulness that ‘There are feelings’ is maintained to the extent of knowledge & remembrance. And he remains independent, unsustained by (not clinging to) anything in the world. This is how a monk remains focused on feelings in & of themselves.

(C. Mind)

“And how does a monk remain focused on the mind in & of itself? There is the case where a monk, when the mind has passion, discerns that the mind has passion. When the mind is without passion, he discerns that the mind is without passion. When the mind has aversion, he discerns that the mind has aversion. When the mind is without aversion, he discerns that the mind is without aversion. When the mind has delusion, he discerns that the mind has delusion. When the mind is without delusion, he discerns that the mind is without delusion.

“When the mind is restricted, he discerns that the mind is restricted. When the mind is scattered, he discerns that the mind is scattered. When the mind is enlarged, he discerns that the mind is enlarged. When the mind is not enlarged, he discerns that the mind is not enlarged. When the mind is surpassed, he discerns that the mind is surpassed. When the mind is unsurpassed, he discerns that the mind is unsurpassed. When the mind is concentrated, he discerns that the mind is concentrated. When the mind is not concentrated, he discerns that the mind is not concentrated. When the mind is released, he discerns that the mind is released. When the mind is not released, he discerns that the mind is not released.

“In this way he remains focused internally on the mind in & of itself, or externally on the mind in & of itself, or both internally & externally on the mind in & of itself. Or he remains focused on the phenomenon of origination with regard to the mind, on the phenomenon of passing away with regard to the mind, or on the phenomenon of origination & passing away with regard to the mind. Or his mindfulness that ‘There is a mind’ is maintained to the extent of knowledge & remembrance. And he remains independent, unsustained by (not clinging to) anything in the world. This is how a monk remains focused on the mind in & of itself.

(D. Mental Qualities)

“And how does a monk remain focused on mental qualities in & of themselves?

[1] “There is the case where a monk remains focused on mental qualities in & of themselves with reference to the five hindrances. And how does a monk remain focused on mental qualities in & of themselves with reference to the five hindrances? There is the case where, there being sensual desire present within, a monk discerns that ‘There is sensual desire present within me.’ Or, there being no sensual desire present within, he discerns that ‘There is no sensual desire present within me.’ He discerns how there is the arising of unarisen sensual desire. And he discerns how there is the abandoning of sensual desire once it has arisen. And he discerns how there is no future arising of sensual desire that has been abandoned. (The same formula is repeated for the remaining hindrances: ill will, sloth & drowsiness, restlessness & anxiety, and uncertainty.)

“In this way he remains focused internally on mental qualities in & of themselves, or externally on mental qualities in & of themselves, or both internally & externally on mental qualities in & of themselves. Or he remains focused on the phenomenon of origination with regard to mental qualities, on the phenomenon of passing away with regard to mental qualities, or on the phenomenon of origination & passing away with regard to mental qualities. Or his mindfulness that ‘There are mental qualities’ is maintained to the extent of knowledge & remembrance. And he remains independent, unsustained by (not clinging to) anything in the world. This is how a monk remains focused on mental qualities in & of themselves with reference to the five hindrances.

[2] “Furthermore, the monk remains focused on mental qualities in & of themselves with reference to the five clinging-aggregates. And how does he remain focused on mental qualities in & of themselves with reference to the five clinging-aggregates? There is the case where a monk [discerns]: ‘Such is form, such its origination, such its disappearance. Such is feeling… Such is perception… Such are fabrications… Such is consciousness, such its origination, such its disappearance.’

“In this way he remains focused internally on the mental qualities in & of themselves, or focused externally… unsustained by anything in the world. This is how a monk remains focused on mental qualities in & of themselves with reference to the five clinging-aggregates.

[3] “Furthermore, the monk remains focused on mental qualities in & of themselves with reference to the sixfold internal & external sense media. And how does he remain focused on mental qualities in & of themselves with reference to the sixfold internal & external sense media? There is the case where he discerns the eye, he discerns forms, he discerns the fetter that arises dependent on both. He discerns how there is the arising of an unarisen fetter. And he discerns how there is the abandoning of a fetter once it has arisen. And he discerns how there is no future arising of a fetter that has been abandoned. (The same formula is repeated for the remaining sense media: ear, nose, tongue, body, & intellect.)

“In this way he remains focused internally on the mental qualities in & of themselves, or focused externally… unsustained by anything in the world. This is how a monk remains focused on mental qualities in & of themselves with reference to the sixfold internal & external sense media.

[4] “Furthermore, the monk remains focused on mental qualities in & of themselves with reference to the seven factors for Awakening. And how does he remain focused on mental qualities in & of themselves with reference to the seven factors for Awakening? There is the case where, there being mindfulness as a factor for Awakening present within, he discerns that ‘Mindfulness as a factor for Awakening is present within me.’ Or, there being no mindfulness as a factor for Awakening present within, he discerns that ‘Mindfulness as a factor for Awakening is not present within me.’ He discerns how there is the arising of unarisen mindfulness as a factor for Awakening. And he discerns how there is the culmination of the development of mindfulness as a factor for Awakening once it has arisen. (The same formula is repeated for the remaining factors for Awakening: analysis of qualities, persistence, rapture, serenity, concentration, & equanimity.)

“In this way he remains focused internally on mental qualities in & of themselves, or externally… unsustained by (not clinging to) anything in the world. This is how a monk remains focused on mental qualities in & of themselves with reference to the seven factors for Awakening.

[5] “Furthermore, the monk remains focused on mental qualities in & of themselves with reference to the four noble truths. And how does he remain focused on mental qualities in & of themselves with reference to the four noble truths? There is the case where he discerns, as it has come to be, that ‘This is stress… This is the origination of stress… This is the cessation of stress… This is the way leading to the cessation of stress.’

[a] “Now what is the noble truth of stress? Birth is stressful, aging is stressful, death is stressful; sorrow, lamentation, pain, distress, & despair are stressful; association with the unbeloved is stressful; separation from the loved is stressful; not getting what one wants is stressful. In short, the five clinging-aggregates are stressful.

“And what is birth? Whatever birth, taking birth, descent, coming-to-be, coming-forth, appearance of aggregates, & acquisition of [sense] spheres of the various beings in this or that group of beings, that is called birth.

“And what is aging? Whatever aging, decrepitude, brokenness, graying, wrinkling, decline of life-force, weakening of the faculties of the various beings in this or that group of beings, that is called aging.

“And what is death? Whatever deceasing, passing away, breaking up, disappearance, dying, death, completion of time, break up of the aggregates, casting off of the body, interruption in the life faculty of the various beings in this or that group of beings, that is called death.

“And what is sorrow? Whatever sorrow, sorrowing, sadness, inward sorrow, inward sadness of anyone suffering from misfortune, touched by a painful thing, that is called sorrow.

“And what is lamentation? Whatever crying, grieving, lamenting, weeping, wailing, lamentation of anyone suffering from misfortune, touched by a painful thing, that is called lamentation.

“And what is pain? Whatever is experienced as bodily pain, bodily discomfort, pain or discomfort born of bodily contact, that is called pain.

“And what is distress? Whatever is experienced as mental pain, mental discomfort, pain or discomfort born of mental contact, that is called distress.

“And what is despair? Whatever despair, despondency, desperation of anyone suffering from misfortune, touched by a painful thing, that is called despair.

“And what is the stress of association with the unbeloved? There is the case where undesirable, unpleasing, unattractive sights, sounds, aromas, flavors, or tactile sensations occur to one; or one has connection, contact, relationship, interaction with those who wish one ill, who wish for one’s harm, who wish for one’s discomfort, who wish one no security from the yoke. This is called the stress of association with the unbeloved.

“And what is the stress of separation from the loved? There is the case where desirable, pleasing, attractive sights, sounds, aromas, flavors, or tactile sensations do not occur to one; or one has no connection, no contact, no relationship, no interaction with those who wish one well, who wish for one’s benefit, who wish for one’s comfort, who wish one security from the yoke, nor with one’s mother, father, brother, sister, friends, companions, or relatives. This is called the stress of separation from the loved.

“And what is the stress of not getting what one wants? In beings subject to birth, the wish arises, ‘O, may we not be subject to birth, and may birth not come to us.’ But this is not to be achieved by wishing. This is the stress of not getting what one wants. In beings subject to aging… illness… death… sorrow, lamentation, pain, distress, & despair, the wish arises, ‘O, may we not be subject to aging… illness… death… sorrow, lamentation, pain, distress, & despair, and may aging… illness… death… sorrow, lamentation, pain, distress, & despair not come to us.’ But this is not to be achieved by wishing. This is the stress of not getting what one wants.

“And what are the five clinging-aggregates that, in short, are stress? Form as a clinging-aggregate, feeling as a clinging-aggregate, perception as a clinging-aggregate, fabrications as a clinging-aggregate, consciousness as a clinging-aggregate: These are called the five clinging-aggregates that, in short, are stress.

“This is called the noble truth of stress.

[b] “And what is the noble truth of the origination of stress? The craving that makes for further becoming — accompanied by passion & delight, relishing now here & now there — i.e., craving for sensuality, craving for becoming, craving for non-becoming.

“And where does this craving, when arising, arise? And where, when dwelling, does it dwell? Whatever seems endearing and agreeable in terms of the world: that is where this craving, when arising, arises. That is where, when dwelling, it dwells.

“And what seems endearing and agreeable in terms of the world? The eye seems endearing and agreeable in terms of the world. That is where this craving, when arising, arises. That is where, when dwelling, it dwells.

“The ear… The nose… The tongue… The body… The intellect…

“Forms… Sounds… Smells… Tastes… Tactile sensations… Ideas…

“Eye-consciousness… Ear-consciousness… Nose-consciousness… Tongue-consciousness… Body-consciousness… Intellect-consciousness…

“Eye-contact… Ear-contact… Nose-contact… Tongue-contact… Body-contact… Intellect-contact…

“Feeling born of eye-contact… Feeling born of ear-contact… Feeling born of nose-contact… Feeling born of tongue-contact… Feeling born of body-contact… Feeling born of intellect-contact…

“Perception of forms… Perception of sounds… Perception of smells… Perception of tastes… Perception of tactile sensations… Perception of ideas…

“Intention for forms… Intention for sounds… Intention for smells… Intention for tastes… Intention for tactile sensations… Intention for ideas…

“Craving for forms… Craving for sounds… Craving for smells… Craving for tastes… Craving for tactile sensations… Craving for ideas…

“Thought directed at forms… Thought directed at sounds… Thought directed at smells… Thought directed at tastes… Thought directed at tactile sensations… Thought directed at ideas…

“Evaluation of forms… Evaluation of sounds… Evaluation of smells… Evaluation of tastes… Evaluation of tactile sensations… Evaluation of ideas seems endearing and agreeable in terms of the world. That is where this craving, when arising, arises. That is where, when dwelling, it dwells.

“This is called the noble truth of the origination of stress.

[c] “And what is the noble truth of the cessation of stress? The remainderless fading & cessation, renunciation, relinquishment, release, & letting go of that very craving.

“And where, when being abandoned, is this craving abandoned? And where, when ceasing, does it cease? Whatever seems endearing and agreeable in terms of the world: that is where, when being abandoned, this craving is abandoned. That is where, when ceasing, it ceases.

“And what seems endearing and agreeable in terms of the world? The eye seems endearing and agreeable in terms of the world. That is where, when being abandoned, this craving is abandoned. That is where, when ceasing, it ceases.

“The ear… The nose… The tongue… The body… The intellect…

“Forms… Sounds… Smells… Tastes… Tactile sensations… Ideas…

“Eye-consciousness… Ear-consciousness… Nose-consciousness… Tongue-consciousness… Body-consciousness… Intellect-consciousness…

“Eye-contact… Ear-contact… Nose-contact… Tongue-contact… Body-contact… Intellect-contact…

“Feeling born of eye-contact… Feeling born of ear-contact… Feeling born of nose-contact… Feeling born of tongue-contact… Feeling born of body-contact… Feeling born of intellect-contact…

“Perception of forms… Perception of sounds… Perception of smells… Perception of tastes… Perception of tactile sensations… Perception of ideas…

“Intention for forms… Intention for sounds… Intention for smells… Intention for tastes… Intention for tactile sensations… Intention for ideas…

“Craving for forms… Craving for sounds… Craving for smells… Craving for tastes… Craving for tactile sensations… Craving for ideas…

“Thought directed at forms… Thought directed at sounds… Thought directed at smells… Thought directed at tastes… Thought directed at tactile sensations… Thought directed at ideas…

“Evaluation of forms… Evaluation of sounds… Evaluation of smells… Evaluation of tastes… Evaluation of tactile sensations… Evaluation of ideas seems endearing and agreeable in terms of the world. That is where, when being abandoned, this craving is abandoned. That is where, when ceasing, it ceases.

“This is called the noble truth of the cessation of stress.

[d] “And what is the noble truth of the path of practice leading to the cessation of stress? Just this very noble eightfold path: right view, right resolve, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, right concentration.

“And what is right view? Knowledge with regard to stress, knowledge with regard to the origination of stress, knowledge with regard to the cessation of stress, knowledge with regard to the way of practice leading to the cessation of stress: This is called right view.

“And what is right resolve? Aspiring to renunciation, to freedom from ill will, to harmlessness: This is called right resolve.

“And what is right speech? Abstaining from lying, from divisive speech, from abusive speech, & from idle chatter: This is called right speech.

“And what is right action? Abstaining from taking life, from stealing, & from illicit sex. This is called right action.

“And what is right livelihood? There is the case where a disciple of the noble ones, having abandoned dishonest livelihood, keeps his life going with right livelihood: This is called right livelihood.

“And what is right effort? There is the case where a monk generates desire, endeavors, arouses persistence, upholds & exerts his intent for the sake of the non-arising of evil, unskillful qualities that have not yet arisen… for the sake of the abandoning of evil, unskillful qualities that have arisen… for the sake of the arising of skillful qualities that have not yet arisen… (and) for the maintenance, non-confusion, increase, plenitude, development, & culmination of skillful qualities that have arisen: This is called right effort.

“And what is right mindfulness? There is the case where a monk remains focused on the body in & of itself — ardent, alert, & mindful — putting aside greed & distress with reference to the world. He remains focused on feelings in & of themselves… the mind in & of itself… mental qualities in & of themselves — ardent, alert, & mindful — putting aside greed & distress with reference to the world. This is called right mindfulness.

“And what is right concentration? There is the case where a monk — quite withdrawn from sensuality, withdrawn from unskillful (mental) qualities — enters & remains in the first jhana: rapture & pleasure born from withdrawal, accompanied by directed thought & evaluation. With the stilling of directed thoughts & evaluations, he enters & remains in the second jhana: rapture & pleasure born of composure, unification of awareness free from directed thought & evaluation — internal assurance. With the fading of rapture, he remains equanimous, mindful, & alert, and senses pleasure with the body. He enters & remains in the third jhana, of which the Noble Ones declare, ‘Equanimous & mindful, he has a pleasant abiding.’ With the abandoning of pleasure & pain — as with the earlier disappearance of elation & distress — he enters & remains in the fourth jhana: purity of equanimity & mindfulness, neither pleasure nor pain. This is called right concentration.

“This is called the noble truth of the path of practice leading to the cessation of stress.

“In this way he remains focused internally on mental qualities in & of themselves, or externally on mental qualities in & of themselves, or both internally & externally on mental qualities in & of themselves. Or he remains focused on the phenomenon of origination with regard to mental qualities, on the phenomenon of passing away with regard to mental qualities, or on the phenomenon of origination & passing away with regard to mental qualities. Or his mindfulness that ‘There are mental qualities’ is maintained to the extent of knowledge & remembrance. And he remains independent, unsustained by (not clinging to) anything in the world. This is how a monk remains focused on mental qualities in & of themselves with reference to the four noble truths…

(E. Conclusion)

“Now, if anyone would develop these four frames of reference in this way for seven years, one of two fruits can be expected for him: either gnosis right here & now, or — if there be any remnant of clinging-sustenance — non-return.

“Let alone seven years. If anyone would develop these four frames of reference in this way for six years… five… four… three… two years… one year… seven months… six months… five… four… three… two months… one month… half a month, one of two fruits can be expected for him: either gnosis right here & now, or — if there be any remnant of clinging-sustenance — non-return.

“Let alone half a month. If anyone would develop these four frames of reference in this way for seven days, one of two fruits can be expected for him: either gnosis right here & now, or — if there be any remnant of clinging-sustenance — non-return.

“‘This is the direct path for the purification of beings, for the overcoming of sorrow & lamentation, for the disappearance of pain & distress, for the attainment of the right method, & for the realization of Unbinding — in other words, the four frames of reference.’ Thus was it said, and in reference to this was it said.”

That is what the Blessed One said. Gratified, the monks delighted in the Blessed One’s words.

NOTE

- Translation of Sutra: Maha-satipatthana Sutta: The Great Frames of Reference” (DN 22), translated from the Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu. Access to Insight (Legacy Edition), 30 November 2013, https://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/dn/dn.22.0.than.html

More articles by this author

Profound simplicity of “Amituofo”: why Nianfo or Nembutsu is a deep, complete practice with innumerable benefits and cannot be dismissed as faith-based: w. full Amitabha Sutra

“Torches That Help Light My Path”: Thich Nhat Hanh’s Translation of the Sutra on the Eight Realizations of the Great Beings

Maha Mangala Sutta, Life’s Highest Blessings, The Sutra on Happiness, the Tathagata’s Teaching to Gods and Men

Miracles of Buddha: With the approach of Buddha’s 15 Days of Miracles, we celebrate 15 separate miracles of Buddha, starting with Ratana Sutta: Buddha purifies pestilence.

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Josephine Nolan

Author | Buddha Weekly

Josephine Nolan is an editor and contributing feature writer for several online publications, including EDI Weekly and Buddha Weekly.