Buddha teaches the Nadi Sutta: overcoming the assumptions of self with the River Sutra; the river of Samsara cannot be escaped by clinging to the notion of an “abiding self”

The underlying theme of this Sutta is “grasping at the idea of self is the root of suffering.”

- Rupa (material form or just “form”)

- Vedana (feelings or “sensation”)

- Sanna (perceptions)

- Sankhara (mental formations)

- Vinnana (consciousness).

This gets to the heart of “self.” Who are we? Are we this? Are we that? Is the self the brain? The heart? The entire body? Some kind of nebulous field of energy? A soul? What is it that reincarnates into this Samsaric world? Generally, we refer to it as “mindtream” or continuity, but it is a difficult topic. (Even when we speak of rebirth, we understand this is also impermanent.) In Buddhist terms, the “I” or self is made up of those “five heaps” or skandas — form, sensation, perception, mental formations, consciousness — none of which are permanent. It is not a soul with an abiding “forever” self.

Nadi Sutta: The River

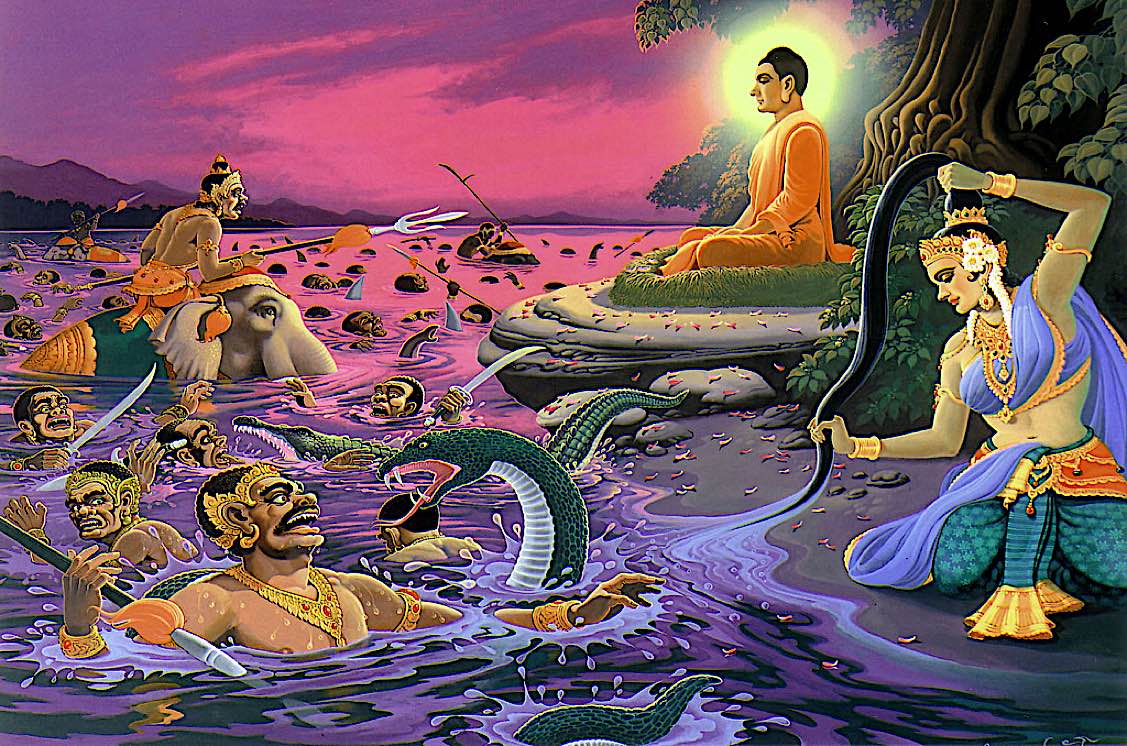

At Savatthi. There the Blessed One said, “Monks, suppose there were a river, flowing down from the mountains, going far, its current swift, carrying everything with it, and — holding on to both banks — kasa grasses, kusa grasses, reeds, birana grasses, & trees were growing. Then a man swept away by the current would grab hold of the kasa grasses, but they would tear away, and so from that cause he would come to disaster. He would grab hold of the kusa grasses… the reeds… the birana grasses… the trees, but they would tear away, and so from that cause he would come to disaster.

“In the same way, there is the case where an uninstructed, run-of-the-mill person — who has no regard for noble ones, is not well-versed or disciplined in their Dhamma; who has no regard for men of integrity, is not well-versed or disciplined in their Dhamma — assumes form (the body) to be the self, or the self as possessing form, or form as in the self, or the self as in form. That form tears away from him, and so from that cause he would come to disaster.

“He assumes feeling to be the self, or the self as possessing feeling, or feeling as in the self, or the self as in feeling. That feeling tears away from him, and so from that cause he would come to disaster.

“He assumes perception to be the self, or the self as possessing perception, or perception as in the self, or the self as in perception. That perception tears away from him, and so from that cause he would come to disaster.

“He assumes (mental) fabrications to be the self, or the self as possessing fabrications, or fabrications as in the self, or the self as in fabrications. Those fabrications tear away from him, and so from that cause he would come to disaster.

“He assumes consciousness to be the self, or the self as possessing consciousness, or consciousness as in the self, or the self as in consciousness. That consciousness tears away from him, and so from that cause he would come to disaster.

“What do you think, monks — Is form constant or inconstant?”

“Inconstant, lord.”

“And is that which is inconstant easeful or stressful?”

“Stressful, lord.”

“And is it fitting to regard what is inconstant, stressful, subject to change as: ‘This is mine. This is my self. This is what I am’?”

“No, lord.”

“…Is feeling constant or inconstant?”

“Inconstant, lord.”…

“…Is perception constant or inconstant?”

“Inconstant, lord.”…

“…Are fabrications constant or inconstant?”

“Inconstant, lord.”…

“What do you think, monks — Is consciousness constant or inconstant?”

“Inconstant, lord.”

“And is that which is inconstant easeful or stressful?”

“Stressful, lord.”

“And is it fitting to regard what is inconstant, stressful, subject to change as: ‘This is mine. This is my self. This is what I am’?”

“No, lord.”

“Thus, monks, any form whatsoever that is past, future, or present; internal or external; blatant or subtle; common or sublime; far or near: every form is to be seen as it actually is with right discernment as: ‘This is not mine. This is not my self. This is not what I am.’

“Any feeling whatsoever…

“Any perception whatsoever…

“Any fabrications whatsoever…

“Any consciousness whatsoever that is past, future, or present; internal or external; blatant or subtle; common or sublime; far or near: every consciousness is to be seen as it actually is with right discernment as: ‘This is not mine. This is not my self. This is not what I am.’

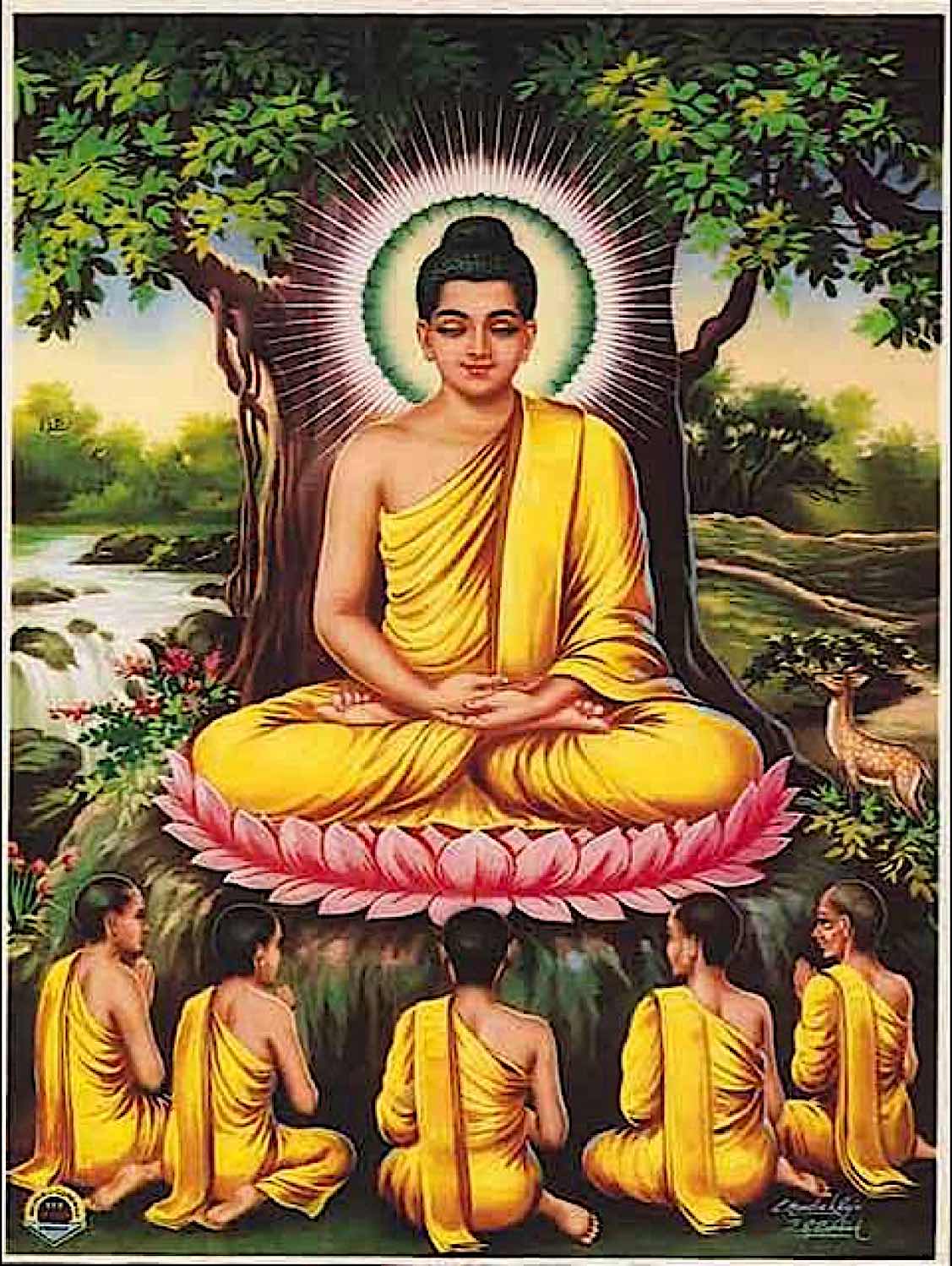

“Seeing thus, the well-instructed disciple of the noble ones grows disenchanted with form, disenchanted with feeling, disenchanted with perception, disenchanted with fabrications, disenchanted with consciousness. Disenchanted, he becomes dispassionate. Through dispassion, he is fully released. With full release, there is the knowledge, ‘Fully released.’ He discerns that ‘Birth is ended, the holy life fulfilled, the task done. There is nothing further for this world.'”

Citation: “Nadi Sutta: The River” (SN 22.93), translated from the Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu. Access to Insight (BCBS Edition), 30 November 2013, .

More articles by this author

Profound simplicity of “Amituofo”: why Nianfo or Nembutsu is a deep, complete practice with innumerable benefits and cannot be dismissed as faith-based: w. full Amitabha Sutra

“Torches That Help Light My Path”: Thich Nhat Hanh’s Translation of the Sutra on the Eight Realizations of the Great Beings

Maha Mangala Sutta, Life’s Highest Blessings, The Sutra on Happiness, the Tathagata’s Teaching to Gods and Men

Miracles of Buddha: With the approach of Buddha’s 15 Days of Miracles, we celebrate 15 separate miracles of Buddha, starting with Ratana Sutta: Buddha purifies pestilence.

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Josephine Nolan

Author | Buddha Weekly

Josephine Nolan is an editor and contributing feature writer for several online publications, including EDI Weekly and Buddha Weekly.