Why Nonviolence or Ahimsa Was Not Explicitly Debated in All Four Councils of Buddhism?

After Buddha’s Mahaparinirvana at Kushinara, capital city of Malla Kingdom, today’s Kushinagar (Uttar pradesh, India), there was a surge of different ideas in Sangha. Thus, the Buddhist councils were convened to safeguard the integrity of th Dhamma and to prevent undue doctrinal diversification.

Within this framework, Ahimsa – or non-violence – stands as one of the core and most fundamental ethical principles of Buddhism.

While Ahimsa formed an essential part of Buddhist moral practice, it received limited explicit attention in the Buddhist councils which focused largely on maintaining doctrinal coherence and disciplinary order. Considering the contextual reason for the limited explicit discussion of Ahimsa in the Buddhist councils allows for a deeper appreciation of the practical orientation of the Buddhist Dhamma.

By Niketan Shegokar, Bio bottom of feature

The Ancient Buddhist Councils: Purpose and Context

The four ancient Buddhist Councils were convened between approximately the 5th century BCE and 1st century CE to address institutional, doctrinal, and disciplinary challenges faced by the Buddhist Saṅgha.

Contrary to modern expectations, these councils were not philosophical conferences, but assemblies focused on preservation rather than more innovation. Their primary objectives were preservation of the Buddha’s teachings (Dhamma), codification, standardization and maintenance of monastic discipline (Vinaya), resolution of doctrinal or disciplinary disputes and protection of unity within the Saṅgha.

Within this framework, ahimsa was treated as a foundational ethical assumption, not a contested doctrine requiring debate.

Related Feature:

Overview of the Four Councils and Their Agendas

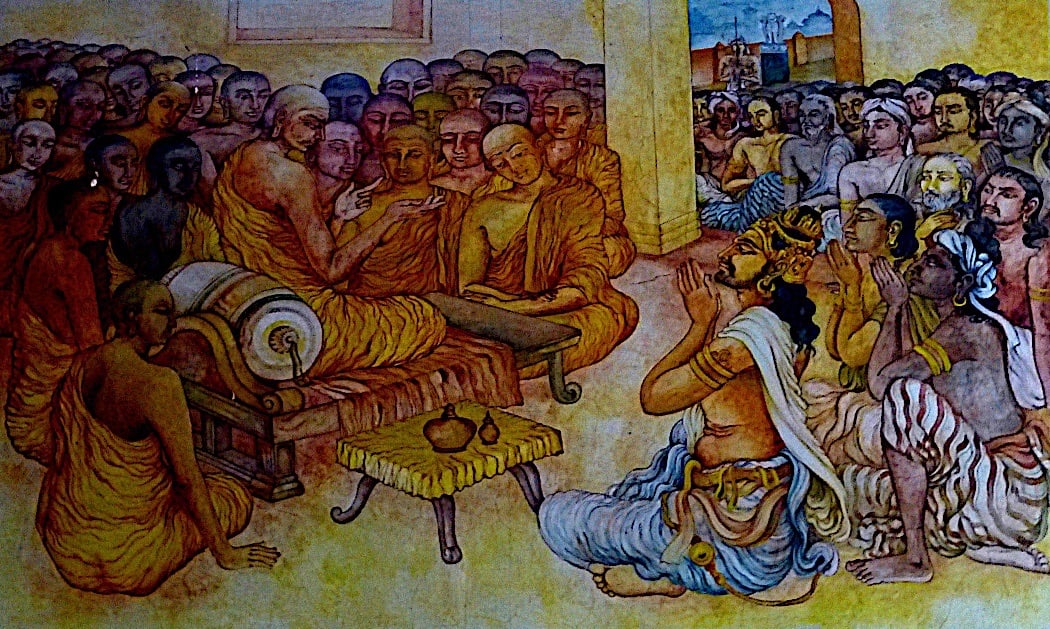

First Buddhist Council (c. 5th century BCE, Rājagṛha)

Convened shortly after the Buddha’s parinirvāṇ by King Ajatshatru of Haryanka dynasty of Magadha which focused on the compilation of teachings and recitation of Vinaya and discourses. The reason Ahimsa was not discussed explicitly was because nonviolence was already embedded in monastic discipline and moral conduct. The concern was accuracy of transmission, not ethical reinterpretation.

Second Buddhist Council (c. 4th century BCE, Vaiśālī)

The Second Buddhist council was convened by King Kalashoka of Sisunaga dynasty of Magadha which was triggered by disciplinary disputes, especially regarding monastic practices and addressed violations of Vinaya rules. The debate was procedural, not ethical. Ahimsa was universally accepted and not under threat; therefore, it did not require formal discussion during this period.

Third Buddhist Council (c. 3rd century BCE, Pāṭaliputra)

Held under Emperor Aśoka the great of Maurya dynasty of Magadha at his captial city Pataliputra, today’s Patna city which aimed to purify the Saṅgha, eliminate doctrinal corruption and address heterodox views. Ahimsa gained political and social expression during this period, especially through Aśoka’s policies (after the famouus Battle of Kalinga), but the council focused on doctrinal clarity, not moral redefinition. This Summit marked the major phase of state-supported Buddhism and the global spread of Dhamma beyond the limits of Indian subcontinent.

Fourth Buddhist Council (c. 1st century CE, Kashmir / Sri Lanka traditions)

Under the rule of King Kaniska I of Kushan Empire, held at kashmir (Sarvastivada tradition) this council marked the formal writing down of Buddhist teachings and the most significant thing is it occurred amid sectarian diversification in the Kingdom. Ahimsa remained absent as a debate topic in this council too because the council addressed preservation in the face of fragmentation, not ethical innovation. Ahimsa was considered axiomatic, shared across schools. It was considered so fundamental and self-evident that the scholars did not find any necessity to discuss the idea at all.

Why Ahimsa Was Not Explicitly Debated in All Four Councils

i) Ahimsa Was a Moral Given. It was not a Contested Doctrine. Modern scholars emphasize that ahimsa in Buddhism functioned as an ethical presupposition, comparable to grammar in language i.e. it structured practice but was not debated unless violated.

ii) These councils were conservative, not reformist because they aimed to preserve orthodoxy and prevent distortion. They were not platforms for ethical expansion, philosophical innovation and social reform debates. Thus, ahimsa remained implicit rather than explicit.

iii) They focused on Vinaya over Ethical Theory. Ethics in Buddhism is primarily practice-oriented, embedded in the precepts, monastic rules and daily conduct. Ahimsa was enforced through discipline, not discourse, in day-to-day life.

iv) Ethical Crisis was absent around nonviolence. Unlike doctrinal schisms or disciplinary lapses, there was no widespread controversy rejecting nonviolence within the early Saṅgha that necessitated council-level intervention. So naturally, no need was felt to discuss it further.

v) Buddhism’s Psychological Framing of Ethics was designed the way it would not face conflicts. Because Buddhist ethics locates violence in mental intention, it was addressed through meditation, mind training and moral cultivation. This reduced the need for institutional debate.

Significance of This Silence

The absence of explicit discussion on ahimsa in the councils is not evidence of neglect, but of ethical internalization. Buddhist nonviolence survived precisely because it was practiced rather than legislated, assumed rather than enforced and cultivated internally rather than debated externally. This distinguishes Buddhism from traditions that required repeated legal or theological reaffirmation of nonviolence.

References

- Gombrich, R. (2009). What the Buddha thought. Equinox Publishing.

- Keown, D. (2005). Buddhist ethics: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Harvey, P. (2013). An introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, history and practices (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Skilton, A. (1994). A concise history of Buddhism. Windhorse Publications.

- Strong, J. S. (2015). Buddhisms: An introduction. Oneworld Publications.

- Williams, P., Tribe, A., & Wynne, A. (2012). Buddhist thought: A complete introduction to the Indian tradition (2nd ed.). Routledge.

* By Photo Dharma from Penang, Malaysia – 013 First Council at Rajagaha, CC BY 2.0, Wiki Commons>>

**By Photo Dharma from Penang, Malaysia – 014 King Asoka at the Third Council, CC BY 2.0, Wiki Commons>>

More articles by this author

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Niketan Shegokar

Author | Buddha Weekly

Niketan at time of writing, is a final year MBBS student and a history enthusiast. He has an interest in research and writing, especially over the last 3 years.