What are deities? Not other than “the qualities of the fully awakened… latent within us.” Who is Guru? “the pointer to these qualities”

The concept of “deity” is the most misunderstood aspect of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism. Buddha did not discuss a creator God. Why, then do we speak of “deities” in Buddhism? The concept of “Guru” is another largely misunderstood concept.

The great Kyabje Garchen Rinpoche introduces the concept:

“…Every deity is the same… in this world there are so many diverse people, each with different faces, bodies, and styles of clothing. But the Buddha Nature of their inner minds is singular. This nature, shared by Buddhas and sentient beings alike, has but one basis. The only difference between Buddhas and sentient ones is the scope of their love, compassion, and bodhicitta… however, there are no differences within the mind that is Buddha Nature.” [1]

With the help of some of the great teachers — His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Kyabje Garchen Rinpoche, Lama Thubten Yeshe, Lord Atisha and Shakyamuni Buddha — we’ll try to point to the true nature of deity, guru — and you!

The most eminent Kyabje Garchen Rinpoche, explains the basis:

“Since all sentient beings possess the mind of Buddha Nature—the very cause of the buddhas—they are like the Buddhas’ children. Among them, one who obtains a precious human body endowed with freedoms and connections is exceedingly rare. When such a person gives rise to love, compassion, and bodhicitta, it is like the coronation of a monarch. Whoever receives the bodhisattva’s vow is like a king ascending the throne. Further, for practitioners of secret mantra, the pure deity with ornaments and implements is the natural physical expression of bodhicitta.”

In Buddhism, Yidam Deity, Guru, and “I” are not separate

Garchen Rinpoche explained the danger of misinterpreting the “deity” in Buddhism. In his teaching on Vajrakilaya, he warned against the danger of regarding “the deity as real and concrete, perceiving the yidam as no different from an ordinary being.” This is one of the biggest misconceptions.

Another great teacher, Lama Thubten Yeshe, described deities in great detail in Introduction to Tantra: A Vision of Totality[2]:

“Tantric meditational deities should not be confused with what different mythologies and religions might mean when they speak of gods and goddesses. Here, the deity we choose to identify with represents the essential qualities of the fully awakened experience latent within us. To use the language of psychology, such a deity is an archetype of our own deepest nature, our most profound level of consciousness. In tantra we focus our attention on such an archetypal image and identify with it in order to arouse the deepest, most profound aspects of our being and bring them into our present reality.”

Many people misunderstand not only the concept of deity but also the role of “Guru” in Mahayana Buddhism. It may become even more confusing — which is why it’s important to have a good teacher — if we try to grasp the profound, but the elusive concept that the Yidam deity, Guru and “I” are not separate.

Dalai Lama explains “deities”

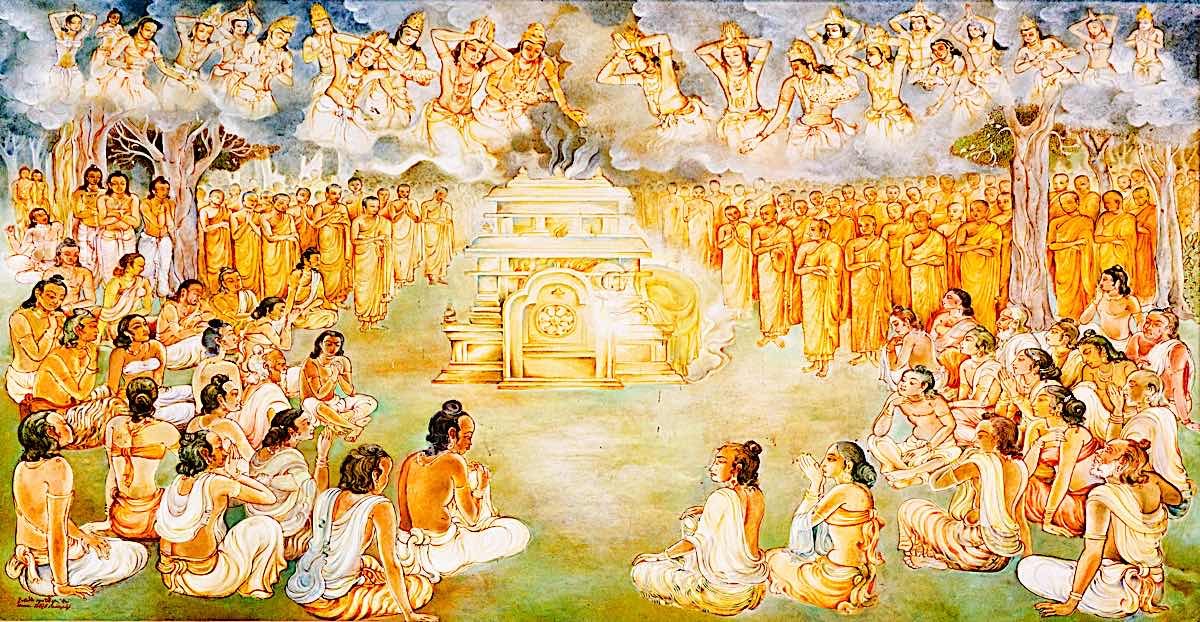

Understanding aspects of enlightenment as “deities” is not the same as “worshipping gods.” The concept of deity in Buddhism is entirely different from faiths that believe in “creators gods.” In Buddhism, the creator is not other than Karma, cause, and effect — and there literally never was a beginning, just endless cycles of millennium after millennium of Samsara. The great Buddhaghosa, a Theravadan commentator, clarifies the Buddhist point-of-view:

“For there is no god, the maker of the conditioned world of rebirths. Phenomena alone flow on. Conditioned by the coming together of causes.” (Visuddhimagga 603)

In other words, “deva” in Buddhism has nothing to do with creator gods. What, then does it relate to? The Dalai Lama, in the forward to Mystical Arts of Tibet explained the “deity” very concisely[3]:

“The deities themselves are regarded as representing particular characteristics of enlightenment.

For example, Manjushri embodies wisdom and Avalokiteshvara (Chenrezig) embodies compassion.

Paying respect to such deities, therefore, has the effect of paying respect to wisdom and compassion, which in turn functions as an inspiration to acquire those qualities within ourselves.”

Deity is not “other”

In fact, when we say “the deity arises from the Guru” this doesn’t mean Guru is above Buddha or vice versa. At the ultimate level, Buddha, Guru and “I” — or “you” — are one nature, Buddha Nature.

The meditational deity, which is a manifestation of Buddha’s Enlightened Body, Speech and Mind, arises from the Guru, as a teacher — not because they magically manifested the deity, but because they guided us and instructed us as previously guided by a long lineage of great yogis and yoginis. In fact “deity” arises from ourselves, from our mind, our Buddha Nature, which is no different from that of Buddha or Guru. In other words, Yidam deities arise from Buddha, Guru, and you. Not one, or the other, or these two and not that one. In Vajrayana, the goal is to pierce the illusory veil of dualistic thinking.

The “Changeless Companion”

Bear with us, we’ll break it down with the help of some great teachers, notable among them the great Kyabje Garchen Rinpoche:

“It is said in the common development-stage texts that the root of both samsara and nirvana is the mind. If one recognizes the actual condition of the mind just as it is, whichever deity one practices, one will know that deity to be the mind itself. The yidam is the guardian and protector of the mind. When one understands the qualities of the deity’s knowledge, love, and capability, one will know him or her to be a changeless companion.

“It is through the yidam’s steadfast friendship that one will become able to accomplish all the common and uncommon siddhis from now until the state of buddhahood is attained. Conversely, even though one may be diligent in deity yoga, if this point is not understood, one will end up practicing an independently existent, ordinary deity. This means that one will regard the deity as real and concrete, perceiving the yidam as no different from an ordinary being.” [1]

Deity is a poor translation

“Deity,” is perhaps a poor translation of the concept of Yidam. The concept of “Deity” is wholly insufficient for the translation task — at least the normally accepted definition of deity, which, according to Oxford is: “a god or goddess … the creator and supreme being … divine status, quality, or nature.” Buddhist deities are really not associated with these concepts.

Since the highest form of Buddhist understanding transcends ego — and god, goddess, supreme being or divine status are all “ego concepts” — the word is entirely wrong as a translation of “Buddhist” notions of “Deva.” The closest translation of “Deva” would be “divine, anything of excellence” and in the case of Buddhism, “Enlightened Excellence.”

Enlightened minds are free of ego. This means the concept of visualized deities with 1000 arms is a symbol and skillful means, not a literal, ego-manifested reality. Does that mean they are not real?

No, of course, Yidams are real in the relative sense — our minds make it so — but in ultimate Buddhist reality, they are Oneness with all. In other words, you, me, the Guru and the Yidam, the lineage gurus, the past Mahasiddhas, the Buddha, your aunt, uncle, mother, father, and all your enemies and friends are Oneness in the ultimate reality.

However, as long as we are obscured by Samsara’s dualistic thinking, we perceive them all to be separate. (But that’s a feature for another day!)

One nature, many forms

So, when we talk about the Guru, it is important to remember that the Guru is not “other.” The Guru is actually a reflection of our own Buddha Nature. In other words, the Guru is not above us or separate from us — the Guru is actually a manifestation of our own highest potential. When we bow to the Guru — or to the Yidam image — we are also bowing to the Buddha Nature we aspire to within ourselves.

The same goes for the Yidam deity. The Yidam may take on any form — male, female, non-gender specific, human, animal, wrathful or peaceful. The form is not important; what’s important is the quality that the form represents. For example, Tara’s representation of compassion or Manjushri’s wisdom.

The Yidam is also not “an other.” The Yidam is a manifestation of our own highest potential.

When we talk about the Guru and the Yidam, it is important to remember that they are not separate from us. They are actually expressions of our own highest nature. We are all One.

Heart in Buddhism

A Yidam “deity” literally translates as “heart commitment.” Yi means “heart” and Dam means “commitment. Heart is an important concept in Buddhism. As Kyabje Garchen Rinpoche wrote:

“The deity’s heart essence is love and affection.”

Why heart deity? The main reason has to do with our “commitment” to a single practice to help focus our meditations. Another reason is that the heart, in Buddhism, is the seat of “mind” or consciousness and also wisdom. The deity is specifically mapped to our own minds. The third reason, of course, has to do with compassion, metta and karuna, which are defining characteristics of all Buddhist “deities.”

Why is this different from the notion of deity in creator-based faiths? There are two main differences. Yidam deities are always Enlightened Beings — and are of “one mind” with Buddha. Equally important is Bodhichitta.

Again, Kyabje Garchen Rinpoche explains,

“Whichever deity one practices, his or her power derives exclusively from Bodhichitta.”

Lord Atisha: “Practicing one Yidam is practicing all Yidams”

The well-known saying, attributed to Lord Atisha, the great Mahasiddha is often used to clarify the concept: “Practicing one Yidam is practicing all Buddhas.” (paraphrased.) In other words, all Yidams are aspects of Buddha. We practice a particular Yidam to focus on a specific concept, such as “overcoming anger” or “developing compassion.” We might think of Yamantaka for the former, and Avalokiteshvara for the latter — but both have the same ultimate realizations.

His Holiness the 41st Sakya Trizin (now His Holiness Sakya Trichen) said:

“In Buddhist tradition, we have two truths: the relative truth and absolute truth. In absolute truth, there’s no deity. There’s nothing. It’s inexpressible. In other words, it is something that is completely beyond our present way of thinking and being. But relatively, we have everything existing. We have “I,” and “you,” and all this. [4]

Garchen Rinpoche, in part, is saying that all Yidams have the same root, the same source. The various practices are just different ways of looking at Buddha — like different colors in a rainbow. All colors come from one light.

The great teacher clarifies,

“Thus, from the perspective of great accomplishment, there are no contradictions among whichever deities and sadhanas one practices.

“Of course, there are differences in terms of deities’ colors, ornaments, implements, and numbers of faces and limbs. When one is drawn to those outer appearances, it is simply a reflection of one’s individual inclinations, interests, and past lives’ connections. So, although practitioners have diverse individual preferences, there is no distinction whatsoever among different deities’ power and force. The mind transmissions of all wisdom deities are the same.” [1]

In other words, the appearances, names, and symbols are all visualizations to aid us on the path, customized to our particular minds.

Why do we need so many Deity forms?

The main reason has to do with the explanation above, but the great guru Garchen Rinpoche clarifies,

“…In this world there are so many diverse people, each with different faces, bodies, and styles of clothing. But the buddha nature of their inner minds is singular.”

H.E. Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche, the Third, wrote:

“Why are there so many? Yidams are visualized pure forms that manifest from dharmadhatu’s empty essence as the lucid self-display of our Lama’s compassion.” The goal of Yidam practice is critical to understanding these forms: ” What is the purpose of Vajrayana practice? Purifying one’s impure perception of all appearances and experiences.”

The role of the Guru

So, what is the role of the Guru? The main role of the Guru is to help us realize our own Buddha Nature — which is none other than their own Buddha Nature. In other words, when we see the Guru, we are seeing a reflection of ourselves.

The Guru’s job is to help us remember our true nature. The word “guru” actually means “dispeller of darkness.” In other words, the guru is like a light that dispels the darkness of ignorance.

Garchen Rinpoche said,

“One could say that all spiritual teachers are the same in that they each have attained complete and perfect buddhahood. Nevertheless, their activities are not identical. The highest and most sublime among them is the one who can induce others to generate bodhichitta spontaneously and effortlessly. Such a guru need not say much; his or her very presence is enough to guide disciples along the path.”

So, the role of the Guru is not to give us something that we don’t already have — but to help us remember what we already have.

Misunderstanding the Guru

What is often misunderstood about Guru yoga is that the relationship between student and teacher is not one of servitude. The student is not trying to become the slave of the teacher. The student-teacher relationship in Buddhism (and particularly in Vajrayana) is one of equals. The difference is that the teacher has more experience, and thus can help guide the student along the path. The teacher is not a “dictator,” but a friend, someone who has been down the road before, and can offer help and guidance.

The word “guru” comes from two Sanskrit words: gu means “darkness,” and ru means “light.” So a guru is someone who dispels the darkness, or ignorance, of the student.

The relationship between student and teacher is one of trust. The student trusts that the teacher knows the way, and is willing to follow the guidance of the teacher. In turn, the teacher agrees to teach only those things that will benefit the student. It is a relationship based on trust, respect, and friendship — not servitude. In fact, the language used between teacher and student is often “Dharma friend.”

In Vajrayana Buddhism, you can, and probably will, have multiple gurus in your lifetime. In the same way as we loftily view “all Yidams are of one nature” we likewise see all our Gurus as our Guru. For example, in Guru Yoga, we are instructed, if we doing visualization, to see all our Gurus above our head — often with the Yidam at their hearts (for example), who then merge into one. Then, that one merges into you. In other words, all the gurus, yidams — and you — merge into one.

The “I” in Buddhism

There is no separate “I” in Buddhism. This is perhaps the most difficult concept for Westerners to understand. We are so used to thinking of ourselves as separate individuals, with our own thoughts, feelings and experiences. But in Buddhism, there is no such thing as a separate “I.”

What we call “I” is just a collection of five aggregates: form, feeling, perception, mental formations and consciousness. These five aggregates are always changing; they are not static. And they are not separate from each other.

The idea of a separate “I” is just an illusion. It is like a mirage in the desert. When we look at it, we think there is water there, but when we get closer, we see that there is nothing there at all.

In the same way, when we look at ourselves, we think there is a separate “I” there, but when we examine ourselves more closely, we see that there is no such thing. We are just a collection of fleeting thoughts and emotions, always changing, never static.

This does not mean that we do not exist. We do exist, but not in the way that we think we do. We exist as a part of the ever-changing flow of life.

Deity, Guru, and I (you) are not separate

In conclusion, it is important to understand that in Buddhism, the concepts of Deity, Guru and “I” are not separate. They are all aspects of Buddha, and they are all connected. Although we recognize and honor the experience, lineage and teachings our teachers convey to us, never-the-less, the best relationship between student and teacher is one trust and respect. And, the dualistic concept of a separate “I” is just illusory.

[1] Garchen Rinpoche, Kyabje. Vajrakilaya, Shambhala.

[2] Introduction to Tantra: A Vision of Totality, by Lama Thubten Yeshe [1987], p. 42

[3] Mystical Arts of Tibet, forward by His Holiness the Dalai Lama

More articles by this author

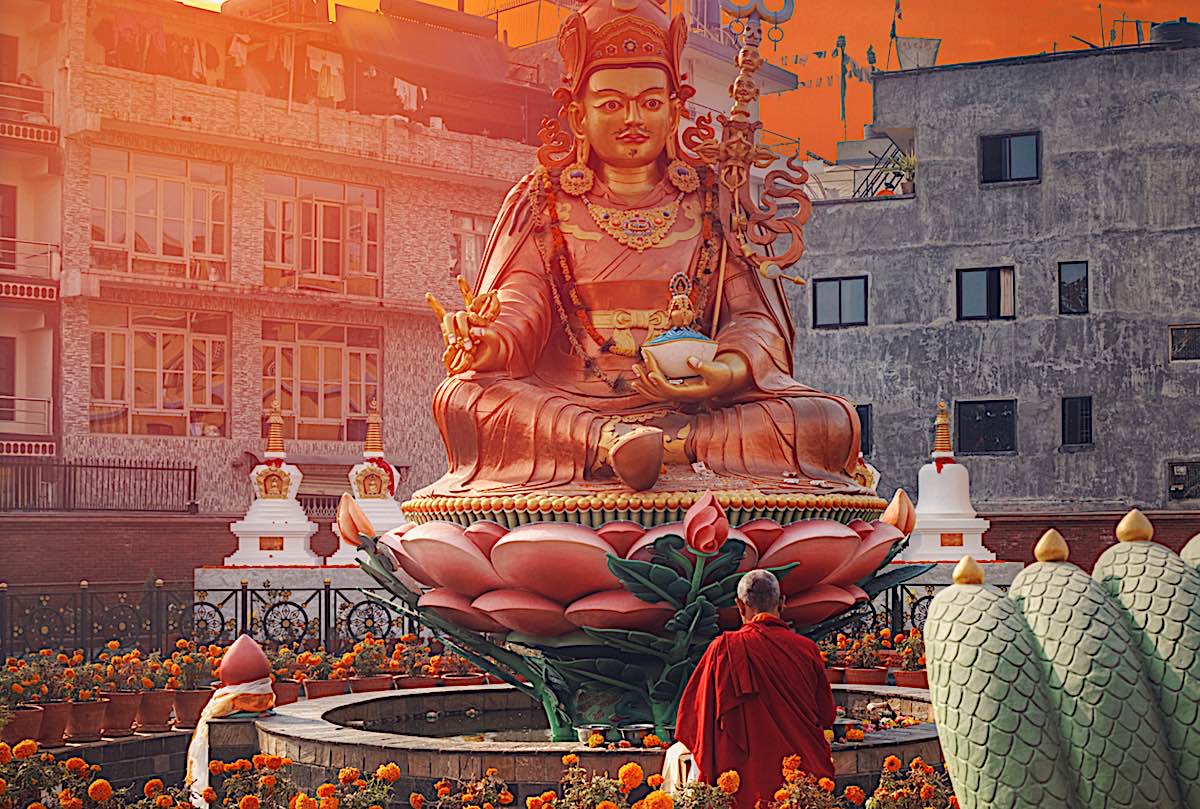

Guru Rinpoche is ready to answer and grant wishes: “Repeat this prayer continuously” for the granting of wishes

VIDEO: Vajrapani Vajra Armor Mantra: Supreme Protection of Dorje Godrab Vajrakavaca from Padmasambhava

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Lee Kane

Author | Buddha Weekly

Lee Kane is the editor of Buddha Weekly, since 2007. His main focuses as a writer are mindfulness techniques, meditation, Dharma and Sutra commentaries, Buddhist practices, international perspectives and traditions, Vajrayana, Mahayana, Zen. He also covers various events.

Lee also contributes as a writer to various other online magazines and blogs.