A Simple Step-by-step Mindfulness Meditation Guide

The benefits and virtues of mindfulness are well established. Today, more than ever, finding a way to calm your inner world and reaching a state of peace is essential. What bothers most people attempting mindfulness as a practice is the lack of an immediate result. Persisting with the routine and learning as one progresses in the practice of meditation is known to the medical and broader community as being adept at reducing harmful side effects of many mental health problems rampant in today’s society.

By Amanda Dudley

(Bio below.)

Buddha taught mindfulness in the 6th century BC. [See this feature with the English version of the Great Mindfulness Sutra, as taught by Buddha.] The practice has always a way to connect to our Buddha Nature and the intricacies of our minds. Successful practice requires dedication, but stress-reduction benefits can be almost immediate. Although we don’t need courses and books to teach mindfulness, if we get stuck, there are over 120 helpful features on Buddha Weekly, and a quick search will reveal many courses, books, and teachers ready to help us. So, the following meditation tips draw on a vast history and corpus of knowledge. Here, I hope to give you a “quick start” guide to mindfulness, known as the “body scan.”

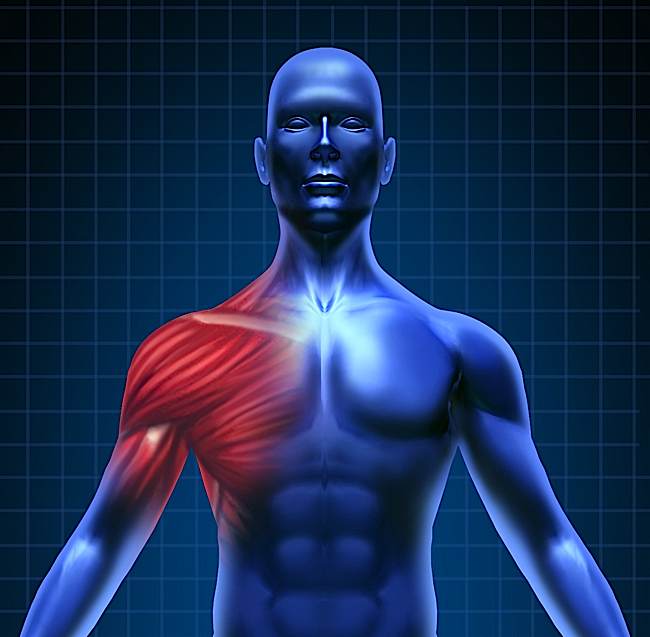

The Body Scan

Perhaps the most potent introduction to mindfulness meditation is the body scan — sometimes called the sweeping meditation. Tying together our mind and our body, exploring the connection, the relationship between these two facets is paramount. Here follows a step-by-step guide to the body scan technique:

- Make yourself comfortable; lying down is best

- Close your eyes and gently focus your attention between your eyebrows

- Take several slow and deep breaths

- Starting with your feet and toes, clench their muscles as tight as you can

- Hold for two breathes, then release them

- Work your way up through your body, giving tension and release to each part

- Repeat this, in segments, your upper legs, your abdomen, etc., until you reach your head

- Once all your body has individually been given the tension and the release, engage all your muscles and fibers at once.

- Repeat this whole body tightening five times

- Relax

The body scan works so well because it provides a way to differentiate between action and inaction. Mindfulness is the act of being aware of your body, your thoughts, your embeddedness in the surrounding world.

Once you’ve completed a body scan, you might be ready to fall asleep. That’s ok. However, if you are practicing in the morning or afternoon, this wouldn’t be too productive, which leads to the next step – establishing a routine.

Routine is essential

Mindfulness is a marathon, not a sprint. In order to reap the benefits, regular and frequent attempts must be made. Daily meditation can provide illuminating insights and help you to solve problems or be more flexible when it comes to life’s challenge. The morning and the evening are natural bookends to the day. These can be excellent times to commit, for twenty minutes or so, to get in tune with your body.

Another way to make mindfulness part of your routine is to set a calendar reminder or alarm. If you want to practice during a lunch break at work or university, this is a superb way to remain on track. There is no set-in-stone best time to meditate. Finding what works for you is the key.

Mindfulness is not about sitting

Mindfulness is not always about sitting in a lotus pose or lying down. Being aware of your surroundings and actions can take place at any time: on the commute, while cooking dinner, or maybe doing a hobby you enjoy. [For example, see our feature on “Skateboarding to Mindfulness>>]

There are techniques that you can use to incorporate mindfulness. It may seem counter-intuitive to meditate while being active, but learning how to meditate deeply on mundane tasks allows us to make more time for ourselves in a hectic world.

The clue is in the name

Our minds are active beasts. One study from 1990 showed that our inner voice could produce 4,000 words per minute[1]. That’s almost ten times faster than our verbal speech. Mindfulness is not necessarily slowing down this rapid pace, but engaging with all of it, being aware of those ‘4,000 words’, which in the course of an hour could produce enough content for a novel. Such is the rich tapestry of our inner world.

So then, the task of being mindful of our actions and our thoughts can help marry together the different speeds at which we operate. An example of this is to take a small sweet or a piece of onion if you are feeling adventurous and place it in your mouth.

Do not attempt to eat the piece in one quick go. Your task is to feel and be aware of the sensations that accompany the object in question. Bitter tastes may provoke us to recoil. Sweet flavors may feel enjoyable. Engaging our minds on what is happening to us in the present moment is what makes mindfulness so powerful.

- Our mindfulness section on Buddha Weekly with many features>>

- Our meditation section on Buddha Weekly with many features>>

Main photo credit: by Keegan Houser on Unsplash

[1]The Atlantic

More articles by this author

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Amanda Dudley

Author | Buddha Weekly

Amanda Dudley is a writer, lecturer, and education specialist who holds a PhD in History from Stanford University. Her work involves American and world history, in addition to teaching strategies and approaches in schools for students with learning disabilities. She also works for an essay writing website, where she offers academic writing help to students on a range of subjects.