Why debate is indispensible in Buddhism demonstrated by Manjushri vs Shakyamuni Buddha in Mahavaipulya Sutra

Debate is almost synonymous with Buddha’s teaching method — that’s not even debatable.

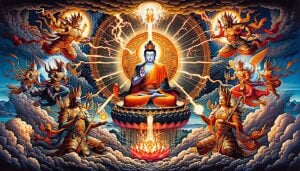

Imagine the Sage teacher, the Conqueror Shakyamuni Buddha debating with the great Wisdom Bodhisattva Manjushri. Now, imagine the topic is the very state of Buddhahood — and the nature of Emptiness. This cuts to the heart of the differences between eternalism and nihilism and the true nature of Emptiness — a vast and profound topic.

What better way to teach, than through debate? Debate is called the “sharp weapon” and the metaphorical “weapon” of Manjushri is his wisdom sword, seen in classic depictions. Buddha was more likely to challenge with sharp questions and debate than by “preaching.” Buddhism is one of the great Wisdom traditions. For that reason, debate is possibly the most important teaching method.

In this magnificent Sutra Buddha debates Manjushri and Manjushri debates Sabhuti — in classic teaching style: “the sharp wisdom sword of Manjushri.”

Manjushri and Buddha Debate

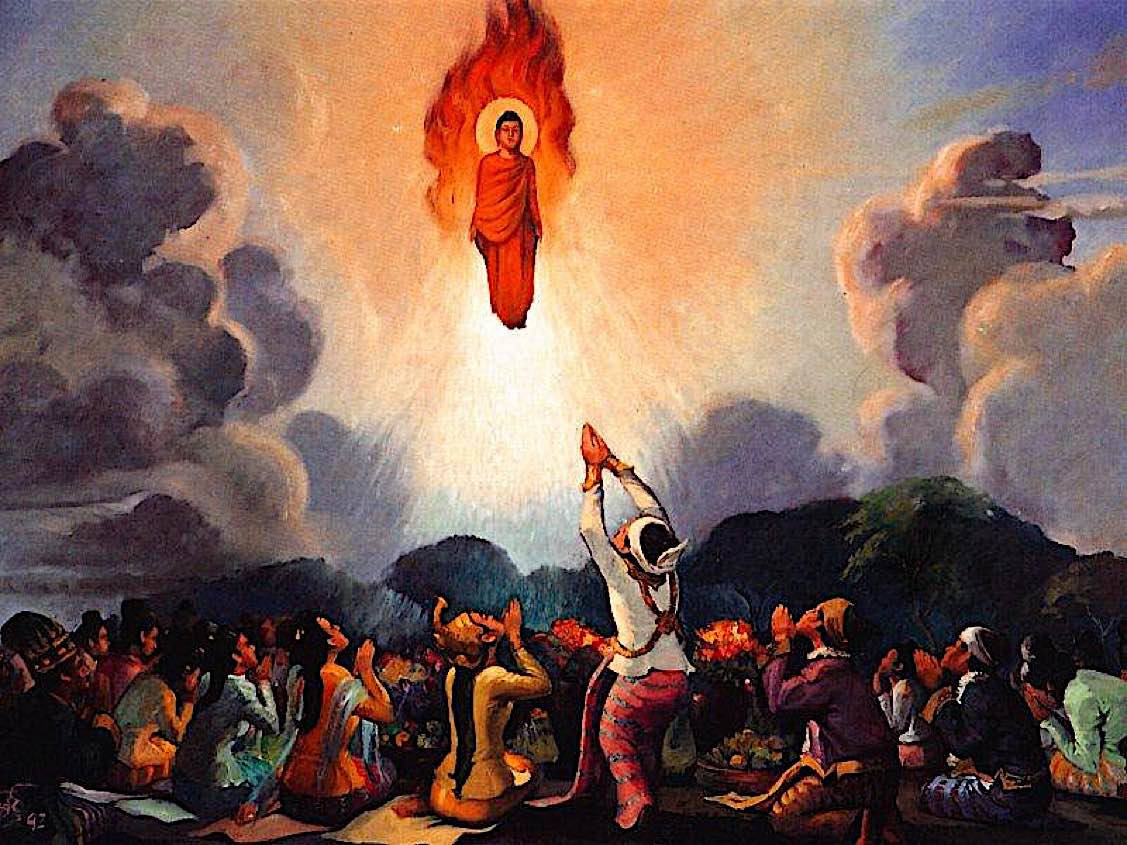

Debate is an analytical method that winds its way through many sutras. Buddha debates students, students debate students, spiritual leaders from other traditions debate the Buddha — there are even “epic” magical debates where Buddha displays miracles to end the argument.

Buddha demonstrated, in Sutra, that the best way to teach difficult concepts was analytical. In Buddhism analytical debate allowed students draw their own conclusions. This is exemplified in the many statues and paintings of Buddha displaying the mudra of debate, or Vitarka Mudra.

Debate is the time-honored teaching method of Buddhism. Buddha didn’t always simply answer a student’s question in the sutras. Many of the discourses use the technique of teacher-student exchanges. Buddha taught by asking provocative questions, then challenging the answers with more “leading questions.” In the same way, Buddha asked Avalokiteshvara to define Emptinesss in the Prajnaparamita Sutras, here, in the Sutra of the Inconceivable State of Buddhahood, he similarly asks Manjushri for clarity.

Debate, in fact, would later become one of the main teaching methods in temples and monasteries — debate, questions and answers, riddles and challenges.

Questioning the “inconceivable state”

Here, in one of the most important Chan (Zen) Mahayana Sutras, Buddha clarifies the “inconceivable state” using a classic Buddhist teaching technique. He asks Manjushri to answer a series of leading questions — in classic teaching style.

Manjushri was Buddha’s “wisdom” disciple, a Bodhisattva who rose to supreme status as the Wisdom Bodhisattva — evident in this precious sutra. Here, both the teacher (Buddha) and the student (Manjushri) ask each other questions for the benefit of the many listeners.

A Classic Exchange between Manjushri and Buddha

For instance, this classic exchange:

The Buddha asked, “Manjusri, in emptiness, how could there be desire, hatred, and ignorance?”

Manjusri answered, “Right in that which exists there is emptiness, wherein desire, hatred, and ignorance are also found.”

The Buddha asked, “In what existence is there emptiness?”

“Emptiness is said to exist only in words and language. Because there is emptiness, there are desire, hatred, and ignorance.

Debating the Buddha

Nowhere is this exchange more evident than in this sutra when Buddha challenges Manjushri and vice-versa — and Manjushri answered the World-Honored Buddha with his own question. Answering a question with another question is a time-honored Buddhist method of provoking wisdom:

The Buddha asked Manjusri, “Are there any categories in the unconditioned?”

Manjusri answered, “World-Honored One, if there were categories in the unconditioned, then the unconditioned would be conditioned and would no longer be the unconditioned.”

The Buddha said, “If the unconditioned can be realized by saints, then there is such a thing as the unconditioned; how can you say there are no categories in “Things have no categories, and the saints have transcended categories. That is why I say there are no categories.”The Buddha asked, “Manjusri, would you not say you have attained saint-hood?”

Manjusri asked in turn, “World-Honored One, suppose one asks a magically produced person, ‘would you not say you have attained sainthood?’ What will be his reply?”The Buddha answered Manjusri, “One cannot speak of the attainment or non-attainment of a magically produced person.”

Manjusri asked, “Has the Buddha not said that all things are like illusions?”

The Buddha answered, “So I have, so I have.”

“If all things are like illusions, why do you ask me whether or not I have attained sainthood?”

The Buddha asked, “Manjusri, what equality in the three vehicles have you realized?”

Manjushri’s metaphorical sword “cutting through”

Subhuti said, “Manjusri, you are not taking care of the novice Bodhisattvas in teaching the Dharma this way.”

Manjusri asked, “Subhuti, what do you think? Suppose a physician, in taking care of his patients, does not give them acrid, sour, bitter, or astringent medicines. Is he helping them to recover or causing them to die?”

Subhuti answered, “He is causing them to suffer and die instead of giving them peace and happiness.”

Manjusri said, “Such is the case with a teacher of the Dharma. If, in taking care of others, he fears that they might be frightened and so hides from them the profound meanings of the Dharma and instead speaks to them in irrelevant words and fancy phrases, then he is causing sentient beings to suffer birth, old age, disease, and death, instead offing them health, peace, bliss, and nirvana”

In art, the two great Bodhisattvas Manjushri and Avalokiteshvara — representing widom and compassion respectively — are often depicted with Shakyamuni:

Debate in Buddhist teaching: skillful means

Although this sutra is student-teacher debate, as a learning experience, other Sutras famously depict debates with other spiritual leaders, such as Brahmins — inevitably won by Shakyamuni Buddha. Debate is a time-honored Buddhist teaching method.

“From the very inception of the tradition, debate has figured prominently in Buddhism. Perhaps as a result of the multireligious environment of India in which Buddhism developed, or as a natural outgrowth of the analytical emphasis found in its meditative techniques, critical inquiry into the beliefs and assertions of oneself and others resulted in numerous instances, types, and theories of debates over the long history of Buddhism both in India and in the countries to which the tradition migrated.” — Paul Hackett “Debate” on Oxford Bibliographies [1]

Importance of Debate in Wisdom Traditions

By way of context, in ancient India, it was commonly accepted practice that the loser of a debate must follow the winners. Famously, in Tibet, Lama Tsongkhapa’s two main disciples had original challenged him antagonistically to debate. These great pandits, when they lost, realized they must follow their new teacher Lama Tsonkhapa.

Daniel Purdue, in an excellent feature on Tibetan Debate, wrote:

“In India, debate was so valued that, if you lost a debate with an opponent, you would have to convert to the view of that opponent. If you cannot defeat a view, then you are compelled to accept it.” [2]

Mahavaipulya Sutra: The Demonstration of the Inconceivable State of Buddhahood Sutra

—Full sutra in English.

Thus have I heard:

Once the Buddha was dwelling in the garden of Anathapindika, in the Jeta Grove near Shravasti, accompanied by one thousand monks, ten thousand Bodhisattva-Mahasattvas, and many gods of the Realm of Desire and the Realm of Form.

At that time, Bodhisattva-Mahasattva Manjusri and the god Suguna were both present among the assembly. The World- Honored One told Manjusri, “You should explain the profound state of Buddhahood for the celestial beings and the Bodhisattvas of this assembly.”

Manjusri said to the Buddha, “So be it, World-Honored One. If good men and good women wish to know the state of Buddhahood, they should know that it is not a state of the eye, the ear, the nose, the tongue, the body, or the mind; nor is it a state of forms, sounds, scents, tastes, textures, or mental objects. World- Honored One, the non-state is the state of Buddhahood. This being the case, what is the state of supreme enlightenment as attained by the Buddha?”

The Buddha said, “It is the state of emptiness, because all views are equal. It is the state of sign-less-ness, because all signs are equal. It is the state of wish-less-ness, because the three realms are equal. It is the state of non-action, because all actions are equal. It is the state of the unconditioned, because all conditioned things are equal.”

Manjusri asked, “World-Honored One, what is the state of the unconditioned?”

The Buddha said, “The absence of thought is the state of the unconditioned.”

Manjusri said, “World-Honored One, if the states of the unconditioned and so forth are the state of Buddhahood, and the state of the unconditioned is the absence of thought, then on what basis is the state of Buddhahood expressed? If there is no such basis, then there is nothing to be said; and since there is nothing to be said, nothing can be expressed Therefore, World-Honored One, the state of Buddhahood is inexpressible in words ”

The Buddha asked, “Manjusri, where should the state of Buddhahood be sought?”

Manjusri answered, “It should be sought right in the defilements of sentient beings. Why, because by nature the defilements of sentient beings are inapprehensible. Realization of this is beyond the comprehension of Sravakas and Pratyekabuddhas; therefore, it is called the state of Buddhahood.”

The Buddha asked Manjusri “Does the state of Buddhahood increase or decreases.”

“It neither increases nor decreases.”

The Buddha asked, “How can one comprehend the basic nature of the defilements of all sentient beings?”

“Just as the state of Buddhahood neither increases nor decreases, so by their nature the defilements neither increase nor decrease.”

The Buddha asked, “What is the basic nature of the defilements?”

“The basic nature of the defilements is the basic nature of the state of Buddhahood. World-Honored One, if the nature of the defilements were different from the nature of the state of Buddhahood, then it could not be said that the Buddha abides in the equality of all things. It is because the nature of the defilements is the very nature of the state of Buddhahood that the Tathágata is said to abide in equality.”

The Buddha asked further, “In what equality do you think the Tathágata abides?”

“As I understand it, the Tathágata abides in exactly the same equality in which those sentient beings who act with desire, hatred, and ignorance abide.”

The Buddha asked, “In what equality do those sentient beings who act with the three poisons abide?”

“They abide in the equality of emptiness, sign-less-ness, and wish-less-ness.”

The Buddha asked, “Manjusri, in emptiness, how could there be desire, hatred, and ignorance?”

Manjusri answered, “Right in that which exists there is emptiness, wherein desire, hatred, and ignorance are also found.”

The Buddha asked, “In what existence is there emptiness?”

“Emptiness is said to exist only in words and language. Because there is emptiness, there are desire, hatred, and ignorance.

The Buddha has said, ‘Monks! Non-arising, non-conditioning, non- action, and non-origination all exist. If these did not exist, then one could not speak of arising, conditioning, action, and origination. Therefore, monks, because there are non-arising, non-conditioning, non-action, and non-origination, one can speak of the existence of arising, conditioning, action, and origination.’ Similarly, World-Honored One, if there were no emptiness, sign- less-ness, or wish-less-ness, one could not speak of desire, hatred, ignorance, or other ideas.”

The Buddha said, “Manjusri, if this is the case, then it must be, as you said. That who abides in the defilements abides in emptiness.”

Manjusri said, “World-Honored One. It a meditator seeks emptiness apart from the defilements, his search will be in vain How could there be an emptiness that differs from the defilements? If he contemplates the defilements as emptiness, he is said to be engaged in right practice.”

The Buddha asked, “Manjusri, do you detach yourself from the defilements or abide in them?”

Manjusri said, “All defilements are equal [in reality]. I have realized that equality through right practice. Therefore, I neither detach myself from the defilements nor abide in them. If a sramaga or Brahmin claims that he has overcome passions and sees other beings as defiled, he has fallen into the two extreme views. What are the two? One is the view of Eternalism, maintaining that defilements exist; the other is the view of nihilism, maintaining that defilements do not exist.

World-Honored One, he who practices rightly sees no such things as self or other, existence or nonexistence. Why? Because he clearly comprehends all dharmas.”

The Buddha asked, “Manjusri, what should one rely upon for right practice?”

“He who practices rightly relies upon nothing.”

The Buddha asked, “Does he not practice according to the path?”

“If he practices in accordance with anything, his practice will be conditioned. A conditioned practice is not one of equality. Why? Because it is not exempt from arising, abiding, and perishing.”

The Buddha asked Manjusri, “Are there any categories in the unconditioned? ”

Manjusri answered, “World-Honored One, if there were categories in the unconditioned, then the unconditioned would be conditioned and would no longer be the unconditioned.”

The Buddha said, “If the unconditioned can be realized by saints, then there is such a thing as the unconditioned; how can you say there are no categories in “Things have no categories, and the saints have transcended categories. That is why I say there are no categories.”

The Buddha asked, “Manjusri, would you not say you have attained saint-hood?”

Manjusri asked in turn, “World-Honored One, suppose one asks a magically produced person, ‘would you not say you have attained sainthood?’ What will be his reply?”

The Buddha answered Manjusri, “One cannot speak of the attainment or non-attainment of a magically produced person.”

Manjusri asked, “Has the Buddha not said that all things are like illusions?”

The Buddha answered, “So I have, so I have.”

“If all things are like illusions, why do you ask me whether or not I have attained sainthood?”

The Buddha asked, “Manjusri, what equality in the three vehicles have you realized?”

“I have realized the equality of the state of Buddhahood.”

The Buddha asked, “Have you attained the state of Buddhahood?”

“If the World-Honored One has attained it, then I have also attained it.”

Thereupon, Venerable Subhuti asked Manjusri, “Has not the Tathágata attained the state of Buddhahood?”

Manjusri asked in turn, “Have you attained anything in the state of Sravaka-hood?”

Subhuti answered, “The liberation of a saint is neither an attainment nor a non-attainment. ”

“So it is, so it is. Likewise, the liberation of the Tathágata is neither a state nor a non-state.”

Subhuti said, “Manjusri, you are not taking care of the novice Bodhisattvas in teaching the Dharma this way.”

Manjusri asked, “Subhuti, what do you think? Suppose a physician, in taking care of his patients, does not give them acrid, sour, bitter, or astringent medicines. Is he helping them to recover or causing them to die?”

Subhuti answered, “He is causing them to suffer and die instead of giving them peace and happiness.”

Manjusri said, “Such is the case with a teacher of the Dharma. If, in taking care of others, he fears that they might be frightened and so hides from them the profound meanings of the Dharma and instead speaks to them in irrelevant words and fancy phrases, then he is causing sentient beings to suffer birth, old age, disease, and death, instead offing them health, peace, bliss, and nirvana”

When this Dharma was explained, five hundred monks were freed of attachment to any dharma, were cleansed of defilements and were liberated in mind; eight thousand devas left the taints of the mundane world far behind and attained the pure Dharma-eye that sees through all dharmas; seven hundred gods resolved to attain supreme enlightenment and vowed: “In the future, we shall attain an eloquence like that of Manjusri.”

Then Elder Subhuti asked Manjusri, “Do you not explain the Dharma of the Sravaka-vehicle to the Sravakas?”

“I follow the Dharmas of all the vehicles.”

Subhuti asked, “Are you a Sravaka, a Pratyekabuddha, or a Worthy One, a Supremely Enlightened One?”

“I am a Sravaka, but my understanding does not come through the speech of others. I am a Pratyekabuddha, but I do not abandon great compassion or fear anything. I am a Worthy One, a Supremely Enlightened One, but I still do not give up my original vows.”

Subhuti asked, “Why are you a Sravaka?”

“Because I cause sentient beings to hear the Dharma they have not.”

“Why are you a Pratyekabuddha?”

“Because I thoroughly comprehend the dependent origination of all dharmas.”

“Why are you a Worthy One, a Supremely Enlightened One?” “Because I realize that all things are equal in the Dharmadhatu ” Subhuti asked. “Manjusri, in what stage do you really abide?”

“I abide in every stage.”

Subhuti asked, “Could it be that you also abide in the stage of ordinary people?”

Manjusri said, “I definitely abide in the stage of ordinary people.” Subhuti asked, “With what esoteric implication do you say so?” “I say so because all dharmas are equal by nature.”

Subhuti asked, “If all dharmas are equal, where are such dharmas as the stages of Sravakas, Pratyekabuddhas, Bodhisattvas, and Buddhas established?”

Manjusri answered, “As an illustration, consider the empty space in the ten directions. People speak of the eastern space, the southern space, the western space, the northern space, the four intermediate spaces, the space above, the space below, and so forth. Such distinctions are spoken of, although the empty space itself is devoid of distinctions. In like manner, virtuous one, the various stages are established in the ultimate emptiness of all things, although the emptiness itself is devoid of distinctions ”

Subhuti asked, “Have you entered the realization of sainthood and been forever separated from samsara?”

“I have entered it and emerged from it ”

Subhuti asked, “Why did you emerge from it after you entered it?”

Manjusri answered, “Virtuous one, you should know that this is a manifestation of the wisdom and ingenuity of a Bodhisattva. He truly enters the realization of sainthood and becomes separated from samsara; then, as a method to save sentient beings, he emerges from that realization. Subhuti, suppose an expert archer plans to harm a bitter enemy, but, mistaking his beloved son in the wilder-ness for the enemy, he shoots an arrow at him The son shouts, ‘I have done nothing wrong. Why do you wish to harm me?’ At once, the archer, who is swift-footed, dashes toward his son and catches the arrow before it does any harm. A Bodhisattva is like this: in order to train and subdue Sravakas and Pratyekabuddhas, he attains nirvana; however, he emerges from it and does not fall into the stages of Sravakas and Pratyekabuddhas. That is why his stage is called the Buddha- stage. ”

Subhuti asked, “How can a Bodhisattva attain this stage?”

Manjusri answered, “If Bodhisattvas dwell in all stages and yet dwell no-where, they can attain this stage.

“If they can discourse on all the stages but do not abide in the lower stages, they can attain this Buddha-stage.

“If they practice with the purpose of ending the afflictions of all sentient beings, but realize there is no ending in the Dharmadhatu; if they abide in the unconditioned, yet perform conditioned actions; if they remain in samsara, but regard it as a garden and do not seek nirvana before all their vows are fulfilled – then they can attain this stage.

“If they realize ego-less-ness, yet bring sentient beings to maturity, they can attain this stage.”

“If they achieve the Buddha-wisdom yet do not generate anger or hatred toward those who lack wisdom, they can attain this stage.

“If they practice by turning the Dharma-wheel for those who seek the Dharma but make no distinctions among things, they can attain this stage.

“Furthermore, if Bodhisattvas vanquish demons yet assume the appearance of the four demons, they cart attain this stage.”

Subhuti said, “Manjusri, such practices of a Bodhisattva are very difficult for any worldly being to believe.”

Manjusri said, “So it is, so it is, as you say. Bodhisattvas perform deeds in the mundane world but transcend worldly dharmas.”

Subhuti said, “Manjusri, please tell me how they transcend the mundane world.”

Manjusri said, “The five aggregates constitute what we call the mundane world. Of these, the aggregate of form has the nature of accumulated foam, the aggregate of feeling has the nature of a bubble, the aggregate of conception has the nature of a mirage, the aggregate of impulse has the nature of a hollow plantain, and the aggregate of consciousness has the nature of an illusion. Thus, One should know that the essential nature of the mundane world is none other than that of foam, bubbles, mirages, plantains, and illusions; ill it there are neither aggregates nor the names of aggregates, neither sentient beings nor the names of sentient beings, neither the mundane world nor the supra-mundane world. Such a right understanding of the five aggregates is called the supreme understanding. If one attains this supreme understanding, then he is liberated, as he [actually] always has been. If he is so liberated, he is not attached to mundane things. If he is not attached to mundane things, he transcends the mundane world.

“Furthermore, Subhuti, the basic nature of the five aggregates is emptiness. If that nature is emptiness, there is neither ‘I’ nor ‘mine.’ If there is neither ‘I’ nor ‘mine,’ there is no duality. If there is no duality, there is neither grasping nor abandoning. If there is neither grasping nor abandoning, there is no attachment. Thus, free of attachment, one transcends the mundane world.

“Furthermore, Subhuti, the five aggregates belong to causes and conditions. If they belong to causes and conditions, they do not

belong to oneself or to others. If they do not belong to oneself or to others, they have no owner. If they have no owner, there is no one who grasps them. If there is no grasping, there is no contention, and non-contention is the practice of religious devotees. Just as a hand moving in empty space touches no object and meets no obstacle, so the Bodhisattvas who practice the equality of emptiness transcend the mundane world.

“Moreover, Subhuti, because all the elements of the five aggregates merge in the Dharmadhatu, there are no realms. If there are no realms, there are no elements of earth, water, fire, or air; there is no ego, sentient being, or life; no Realm of Desire, Realm of Form or Realm of Formlessness: no realm of the conditioned or realm of the unconditioned; no realm of samsara or realm of nirvana. When Bodhisattvas enter such a domain free of distinctions, they do not abide in anything, though they remain in the midst of worldly beings. If they do not abide in anything, they transcend the mundane world.” When this Dharma of transcending the world was explained, two hundred monks became detached from all dharmas, ended all their defilements, and become liberated in mind. One by one they took off their upper garments to offer to Manjusri, saying, “Any person who does not have faith in or understand this doctrine will achieve nothing and realize nothing.”

Then Subhuti asked these monks, “Elders, have you ever achieved or realized anything?”

The monks replied, “Only presumptuous persons will claim they have achieved and realized something. To a humble religious devotee, nothing is achieved or realized. How, then, would such a person think of saying to himself, ‘This I have achieved; this I have realized’? If such an idea occurs to him, then it is a demon’s deed.”

Subhuti asked, “Elders, according to your understanding, what achievement and realization cause you to say so?”

The monks replied, “Only the Buddha, the World-Honored One, and Manjusri know our achievement and realization. Most virtuous one, our understanding is: those who do not fully know the nature of suffering yet claim that suffering should be comprehended are presumptuous. Likewise, if they claim that the cause of suffering should be eradicated, that the cessation of suffering should be realized and that the path leading to the cessation of suffering should be followed, they are presumptuous. Presumptuous also are those who do not really know the nature of suffering, its cause, its cessation, or the path leading to its cessation, but claim that they know suffering, have eradicated the cause of suffering, have realized the cessation of suffering, and have followed the path leading to the cessation of suffering.

“What is the nature of suffering? It is the very nature of non- arising. The same is true concerning the characteristic of the cause of suffering, the cessation of suffering, and the path leading to the cessation of suffering. The nature of non-arising is sign-less and unattainable. In it, there is no suffering to be known, no cause of suffering to be eradicated, no cessation of suffering to be realized, and no path leading to the cessation of suffering to be followed. Those who are not frightened terrified, or awestricken upon hearing these Noble Truths are not presumptuous. Those who are frightened and terrified are the presumptuous ones.”

Thereupon, the World-Honored One praised the monks, saying, “Well said well said!” He told Subhuti, “These monks heard Manjusri explain this profound Dharma during the era of Kasyapa Buddha. Because they have practiced this profound Dharma before, they are now able to follow it and understand it immediately. Similarly, all those who hear, believe, and understand this profound teaching in my era will be among the assembly of Maitreya Buddha in the future.”

Then the god Suguga said to Manjusri, “Virtuous one, you have repeatedly taught the Dharma ill this world. Now we beg you to go to the Tushita Heaven. For a long time, the gods there have also been planting many good roots. They will be able to understand the Dharma if they hear it. However, because they are attached to the pleasures of their heaven, they cannot leave their heaven and come to the Buddha to hear the Dharma, and consequently they suffer a great loss. ”

Manjusri immediately performed a miraculous feat that caused the god Suguga and all others in the assembly to believe that they had arrived at the palace of the Tushita Heaven. There they saw gardens, woods, magnificent palaces and mansions with sumptuous tiers of railings and windows, high and spacious twenty- storied towers with jeweled nets and curtains, celestial flowers covering the ground, various wonderful birds hovering ill flocks and warbling, and celestial maidens in the air scattering flowers of the coral tree, singing verses in chorus, and playing merrily.

Seeing all this, the god Suguna said to Manjusri, “This is extraordinary, Manjusri! How have we arrived so quickly at the palace of the Tushita Heaven to see the gardens and the gods here? Manjusri, will you please teach us the Dharma?”

Elder Subhuti told Suguna, “Soil of heaven, you did not leave the assembly or go anywhere. It is Manjushri’s miraculous feat that causes you to see yourself in the palace of the Tushita Heaven.”

The god Suguna said to the Buddha, “How rare, World-Honored One! Manjusri has such a command of samádhi and of miraculous power that in an instant he has caused this entire assembly to appear to be in the palace of the Tushita Heaven.”

The Buddha said, “Son of heaven, is this your understanding of Manjushri’s miraculous power? As I understand it, if Manjusri wishes, he can gather all the merits and magnificent attributes of Buddha-lands as numerous as the sands of the Ganges and cause them to appear in One Buddha-land. He can with one fingertip lift up the Buddha-lands below ours, which are as numerous as the sands of the Ganges, and put them in the empty space on top of the Buddha-lands above ours, which are also as numerous as the sands of the Ganges. He can put all the water of the four great oceans of all the Buddha-lands into a single pore without making the aquatic beings in it feel crowded or removing them from the seas. He can put all the Mount Sumerus of all the worlds into a mustard seed, yet the gods on these mountains will feel that they are still living in their own palaces. He can place all sentient beings of the five planes of existence of all the Buddha- lands on his palm, and cause them to see all kinds of exquisite material objects such as those available in delightful, magnificent countries. He can gather all the fires of all the worlds into a piece of cotton. He can use a spot as small as a pore to eclipse completely every Sun and moon in every Buddha-land. In short, he can accomplish whatever he wishes to do.”

At that time, Papiyan, the Evil One, transformed himself into a monk and said to the Buddha, “World-Honored One, we wish to see Manjusri perform such miraculous feats right now. What is the use of saying such absurd things, which nobody in the world can believe?”

The World-Honored One told Manjusri, “You should manifest your miraculous power right before this assembly.” Thereupon, without rising from his seat, Manjusri entered the Samadhi of Perfect Mental Freedom in Glorifying All Dharmas, and demonstrated all the miraculous feats described by the Buddha.

Seeing this, the Evil One, the members of the assembly, and the god Suguga all applauded these unprecedented decals, saying, “Wonderful, wonderful! Because of the appearance of the Buddha in this world, we now have this Bodhisattva who can perform such miraculous feats and open a door to the Dharma for the world.”

Thereupon, the Evil One, inspired by Manjushri’s awesome power, said, “World-Honored One, how wonderful it is that Manjusri possesses such great, miraculous power! And the members of

this assembly, who now understand and have faith in the Dharma through his demonstration of miraculous feats, are also marvelous. World-Honored One, even if there were as many demons as the sands of the Ganges, they would not be able to hinder these good men and good women, who understand and believe in the Dharma.

“I, Papiyan the Evil One, have always sought opportunities to oppose the Buddha and to create turmoil among sentient beings. Now I vow that, from this day on, I will never go nearer than one hundred leagues away from the place where this doctrine prevails, or where people have faith in, understand, cherish, receive, read, recite, and teach it.

More articles by this author

Protection from all Harm, Natural Disaster, Weather, Spirits, Evil, Ghosts, Demons, Obstacles: Golden Light Sutra: Chapter 14

Samantabhadra’s The King of Prayers is the ultimate Buddhist practice how-to and itself a complete practice

The Five Strengths and Powers or pañcabalā in Buddhism — the qualities conducive to Enlightenment: faith, energy, mindfulness, concentration and wisdom

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Lee Kane

Author | Buddha Weekly

Lee Kane is the editor of Buddha Weekly, since 2007. His main focuses as a writer are mindfulness techniques, meditation, Dharma and Sutra commentaries, Buddhist practices, international perspectives and traditions, Vajrayana, Mahayana, Zen. He also covers various events.

Lee also contributes as a writer to various other online magazines and blogs.