Dastan-e-Irfan-e-Budh – The Buddha story as a dastangoi — a performance of an epic

Dastangoi is probably an unfamiliar vehicle to transmit the Buddha’s life and teachings – and the Buddha’s teachings have witnessed several kinds of “vehicles” for their dissemination. Dastangoi is a compound of two Persian words ‘Dastan’ (story, narrative) and ‘goi’ (‘telling’), which together mean to tell a Dastan. “Dastans were epics, often oral in nature, which were recited or read aloud…” according to a website titled “Dastangoi: The re-discovered art of Urdu storytelling,” maintained by one of the doyens of the re-discovery, Mahmood Farooqui.

By Umang Kumar

[Bio below.]

Yet, the dastangoi titled Dastan-e-Irfan-e-Budh — The Story of the Enlightenment of the Buddha — a performance that presented the life of the Buddha, performed on Jun 22 and 23 2019 at the Indian Habitat Center in New Delhi, India, managed to embrace the Buddha story with elan. It delivered a sweeping, though curated, account of the Buddha’s life, employing a mix of languages in its narration, primarily Urdu and Hindi but with judicious snippets from the Pali and Sanskrit as well – the latter two languages associated with traditional Buddhist transmission and literature.

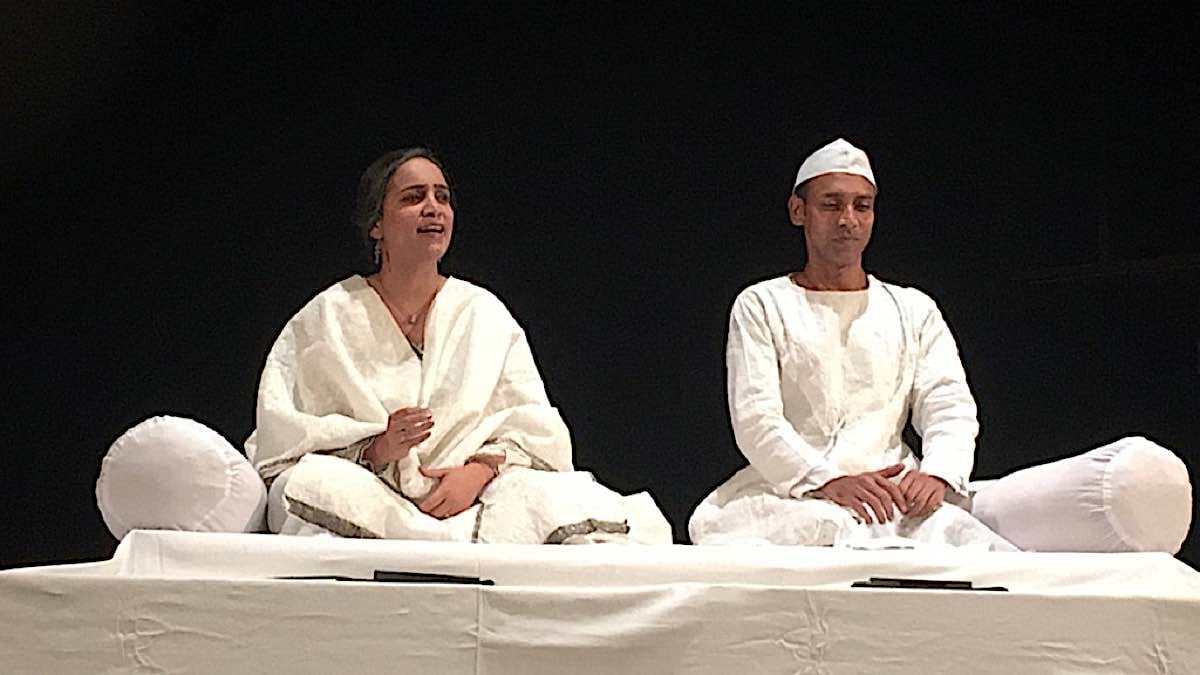

Dastangoi performances have a certain format and a very particular aesthetic. There are one or two dastangos – or storytellers – on the stage. The dastangos are typically clad in all white and sometimes sport a Lucknavi-style white cap, part of a period-costume from the north Indian city of Lucknow. They recite the tale extempore, often alternating if there are two dastangos.

The life story of Buddha as a narrated epic

The life story of the Buddha, known as Siddhartha Gautama after he was born, does not have a very extensive and continuous tradition of popular oral narration and transmission – at least not in India for several centuries now. The 7th-century Chinese Buddhist traveler to India, I-Tsing, does note that the biography of the Buddha in kavya (poetic) form, Buddhacharita, by the poet Ashvaghosha, was read and sung in India quite extensively. Other Buddhist countries, like Japan, Sri Lanka and Myanmar, have had a tradition of various performative arts, especially dance forms, which narrate the story of the Buddha.

Hence, it is even more significant that a mode of storytelling – dastangoi – that has traditionally been employed to regale, inform and popularize various kinds of stories, tales and narratives – from those considered factual to those in the realm of the mythical and fantastical – was utilized to recreate the life of the Buddha.

Hazreen (Urdu: Dear Audience), on one occasion the Tathagata held some leaves in his palm and asked Ananda, “Would you look, Ananda, if all the leaves of this forest are in my palm?” Ananda, understandably shocked, replied: “Tathagata, the forest is so big and it has so many trees and each tree has uncountable leaves…and it is also time for leaves to fall. How is it possible that all leaves would fit in your palm?” The Tathagata smiled and said, “You are right, Ananda. Similarly, there are so many truths hidden in life, whatever fitted in my palm I give you.” Hazreen, we too humbly offer in your esteemed presence the Tathagata’s voice, his stories and episodes from his life to the extent we could collect them.

Sources for the Epic

The Irfan-e-Budh performance in question was enacted by two dastangos, Poonam Girdhani and Rajesh Kumar. It was written by Girdhani. She put together the text of the dastan from a rich variety of sources: there were snippets from the Jataka tradition which recount the past lives of the Buddha and situate the life of the Buddha in historical and cosmological context; included were excerpts from the Sanskrit biography of the Buddha, Buddhacharita, by the poet Ashvaghosha; and also episodes from the so-called canonical texts of the Buddhist tradition, the Nikayas (the Khuddaka Nikaya, to be precise).

However, that was not all – the story was not just limited to traditional material. There was a surprisingly rich collection of retellings and recreations gleaned from other sources as well. There were selections from modern Hindi poet Maithili Sharan Gupt’s poem, Sakhi Woh Mujh Se Keh Kar Jate (Friend, he should have (at least) informed me and then left), the poet’s imagined refrain by Siddhartha’s wife Yashodhara when the future Buddha is supposed to have left surreptitiously from home onto his life as a wanderer; from Independent India’s first law minister, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s re-envisioning of the four fateful signs seen by the Buddha, in his book The Buddha and His Dhamma; the social vision of academic-activist and caste crusader Kancha Illaiah as found in the book God as Political Philosopher; and from the well-known 19th-century biography of the Buddha by Edwin Arnold titled Light of Asia and its Hindi translation by scholar, Ramchandra Shukla.

Girdhani is a theater-person by training and narrates in a blog post the struggle of trying to write a dastan, which is not divided into acts, but has a more free flowing format. The request to write a dastan based on the Buddha’s life-story had been made to her about nine months before the performance by none other that one of the chief revivers of dastangoi in India, Mahmood Farooqui.

Girdhani’s quest to read-up on Buddhist history, lore and retellings in the process of writing the dastan led down a varied path, full of unexpected discoveries. “In reality, I had first become acquainted with the Buddha through the stories by the late Pakistani Urdu writer, Intezar Hussain, who wove various Jataka tales and other Buddhist motifs into his stories.” She read widely and voraciously, from traditional Buddhist accounts including primary sources to a variety of literary works associated with Buddhism, including the Therigatha, the poems of the Bhikkunis.

Four Ingredients of Dastan

As Girdhani explains, there are four ingredients in a dastan that are important: razm or warfare, bazm or a party/gathering, tilism or the magical world, and aiyyari or tricks. She said she wanted to stick to the traditional content of dastans but was aware that she could not bring in the miraculous aspects of the Buddhist story as Buddha himself forbade seeking after miracles. In the end, she says the challenge to maintain a basic dastan format and fidelity to the Buddha’s storyline was fun and energizing to deal with.

A Rich Tapestry of Episodes

The sweeping arc of her story was bookended by the story of the resolve of the bodhisattva Sumedha, the past-life manifestation of Siddhartha Gautama, to attain Buddhahood, and by the attainment of parinirvana by the “current” Buddha in Kushinagar. In between, the dastan wove a rich tapestry of episodes, from sources mentioned above. Both Girdhani and her partner dastango, Rakesh Kumar, essayed a narration that glowed with the ardor that went into crafting the story.

“I read all those books for gaining facts and information about the Buddha, but I ended up using them in a manner so I could interweave my experiences of getting to know the Buddha and his story. That is why the pain of Yashodhara, the love of Amrapali the courtesan – and her protest, the candid voice of the Bhikkunis across thousands of years in the Therigatha, the last meal of the Buddha – all of these, as if on their own account, became part of my dastan.” Girdhani says she was deeply affected by the story of the Buddha and his message of compassion.

“Buddha is first an experience and only then is one able to transcribe his story onto the page,” confesses Girdhani.

Biography of Author

Umang Kumar has been a student of Buddhism for several years now, both formally in academic settings and informally, as a layperson. His interests are in the transmission of the Buddha story and the spread of Buddhism. He is also interested in the Buddhist epistemological tradition. He spent several years in the northeast United States and is currently located in the New Delhi area of India.

More articles by this author

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Umang Kumar

Author | Buddha Weekly

Umang Kumar has been a student of Buddhism for several years now, both formally in academic settings and informally, as a layperson. His interests are in the transmission of the Buddha story and the spread of Buddhism. He is also interested in the Buddhist epistemological tradition. He spent several years in the northeast United States and is currently located in the New Delhi area of India.