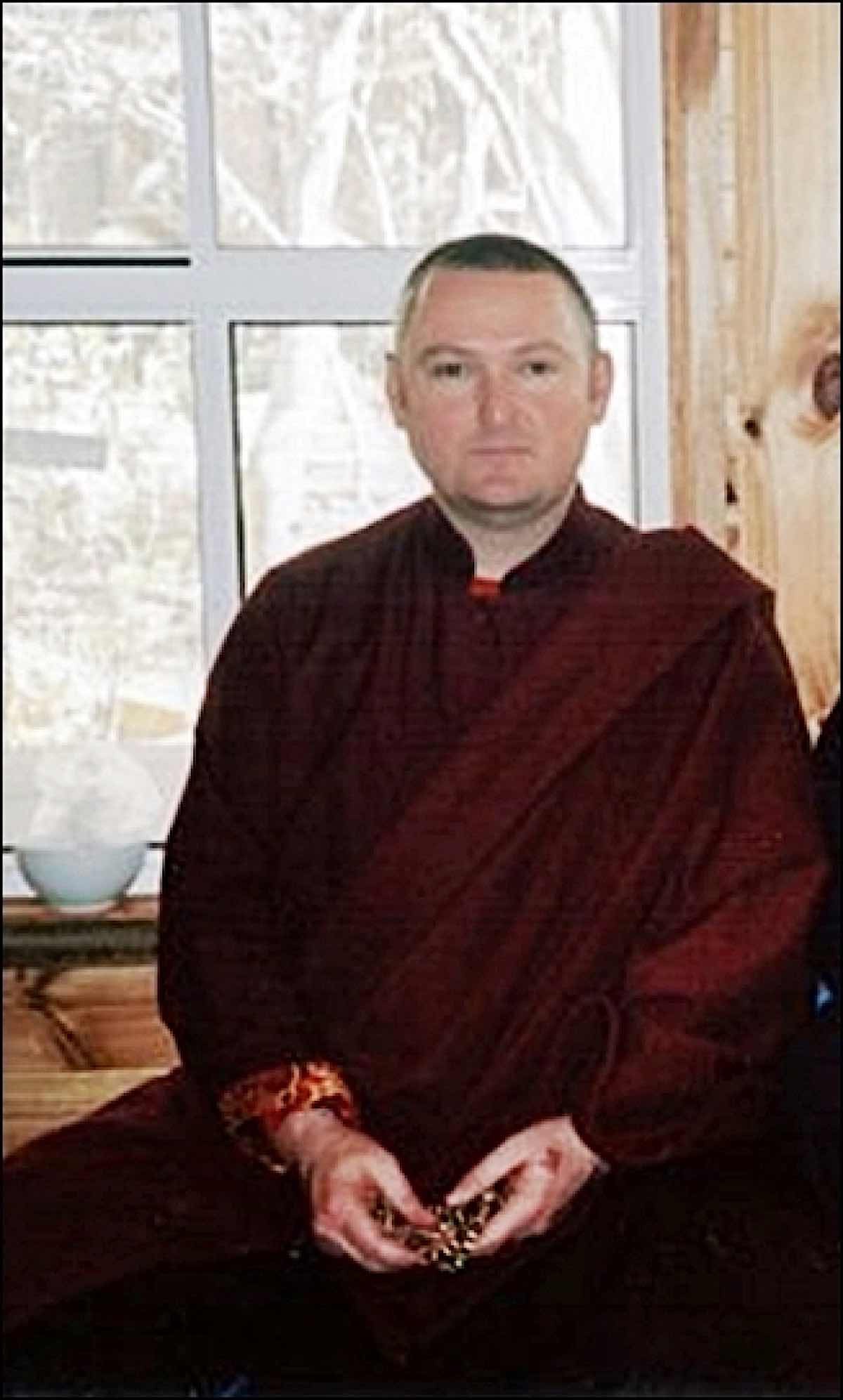

Connecting with Nature of Mind to Overcome Anxiety and Panic: An Interview with Australian Meditation Instructor Pema Düddul

Pema Düddul is the Co-Director of Jalü Buddhist Meditation Centre, a meditation studio in Australia focused on online methods for delivering meditation and mindfulness training.

Pema used Buddhist philosophy and practice to overcome lifelong anxiety and panic and now runs online and face-to-face workshops to help others do the same.

I sat down with Pema to learn more about him and his Buddhist approach to overcoming difficult emotions.

By Jess Stewart

Contributing writer [Bio below]

Pema has been a Buddhist for forty years, discovering at the age of eleven in 1979 that his personal worldview and the tenets of Buddhism were in perfect accordance. He has practised in the Tibetan Buddhist Vajrayana tradition for more than half of that time. Pema considers Dudjom Rinpoche, Jigdral Yeshe Dorje (1904-1987) to be his Heart Lama. He has received teachings from masters in all four schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

In 2005 he received the tantric vows of a ngakpa, the Tibetan Buddhist equivalent of a non-monastic religious minister. He received these vows from one of his principal teachers, Ngakpa Karma Lhundup Rinpoche. It was around this time that he received the Dharma name Pema Düddul. Pema has decades of experience as a Buddhist practitioner. He is an instructor of mindfulness and meditation in Buddhist, educational and corporate settings since 2007. Pema is an openly gay man and founded Jalü Buddhist Meditation Centre with his life partner of fifteen years, Martin Jamyang Tenphel. Pema is also a Ph.D. qualified senior lecturer in creative writing and publishing studies at an Australian University.

Although a respected teacher at a university, in Buddhist settings, Pema describes himself as an “instructor” rather than a “teacher.” He reserves the word teacher for those who have completely realized the path or who are recognized lineage holders.

His online bio quotes him as saying he is “a completely run of the mill Buddhist, an extremely ordinary person, by no means a Buddhist scholar, certainly not a great meditator, not in any way masterful, just trying, like every other Buddhist, to integrate the path of Dharma into everyday life with all its routine challenges.”

Attendees at his workshops describe him as anything but run of the mill, and a deeply kind and insightful practitioner and supportive guide on the Buddhist path.

Pema-la, can you tell me a little about your background?

I was born in 1968, when the White Australia policy, a kind of apartheid, was in full force in Australia. I grew up in a small town (Toowoomba) that was both deeply conservative and deeply Christian. My world was devoid of anything other than Anglo-Saxon monoculture, there were no Buddhist temples, no sangha, no dharma. I had not even heard the word “Buddha” until I was about six or seven years old. I was in grade three, I think, when I first heard the word Buddha.

A boy in my class at primary school came home from his Christmas holidays having been to Japan. He brought to school with him a souvenir I found instantly appealing and compelling – a small carved Buddha head. Seeing that image of the Buddha ignited something in me. I persuaded the boy to do a swap. He gave me the Buddha head and I gave him a rubber turtle (a seriously unbalanced trade). I gleefully took my ill-traded treasure home.

On seeing it my mother told me something I hadn’t known previously – my great, great grandfather had immigrated to Australia from China in the late 1800s and had been a Buddhist. My mother put my fascination with Buddhism down to some tendency inherited from him.

Do you think that’s true, that your interest in Buddhism is inherited?

No, I don’t. A family history DNA test done just a couple of years ago showed I’d inherited 13% of my DNA from a Central Asian ancestor and only 3% from my British ones. The rest is Celtic and Germanic. My interest in Buddhism amounts to much more than 13% of my personality! Even so, my mother believed this inherited tendency explained a lot about my childhood behaviour: my desire for solitude, my poring over the Himalayan section of the atlas, my regular declarations that I should not have been born in Australia but in the Himalayas. I am not convinced that DNA is the answer, but I did have an early passion for the Himalayan region and Buddhism that I cannot explain.

When and how did you become a Buddhist?

I was raised Catholic and had always, from early childhood, felt uncomfortable with that belief system. In 1979 when I was eleven, I took myself off to the local library and found an old Encyclopaedia of Religions on a shelf in the reference section. I went through it from A to Z, from Animism through Wicca to Zoroastrianism. I recently found out that one of my Western meditation heroes, Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo, had also done this. Underage spiritual seekers the world over owe a huge debt to public libraries! When I hit the B section and read the bullet point summary of Buddhist philosophy, I ticked off each point:

- All compounded things are impermanent – Check, yes, believe that.

- All emotional states lead to suffering, either because they are unpleasant in themselves or pleasant yet impermanent – Check, yes.

- All things are devoid of separate, lasting, intrinsic self-nature – Check, yes again.

- There is an achievable state of true peace (Nirvana) – Oh, yes, for sure.

I already believed all these things. I continued through the encyclopedia to “Z” (Zoroastrianism) just in case there was another religion that also believed these things, but none of them came close. So that was the moment I realized I was (already) a Buddhist. From there, I learned what I could about Buddhism from books and rare mentions in newspapers and television. Much of what I knew about Buddhism in those early years came from news reports on the Vietnam War and its aftermath. I was deeply affected by the self-immolation of Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức. Since then, I’ve seen Buddhism as a radical and activist path.

How did you come to practice in the Tibetan tradition?

That happened in the 1980s, around 1985 or 1986. I read Dudjom Rinpoche’s name in a book. The minute I read the name, I knew he was my teacher. That meant by default that I was a Vajrayana Buddhist. The connection I felt with Dudjom Rinpoche deepened later when I learned more about him from other books. Sadly, I never met him. He passed away in 1987 when I was only 19, which causes me daily grief.

A year before Rinpoche passed away, around my eighteenth birthday, I was diagnosed with Generalised Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Though the diagnosis came then, I recognize now I had been anxious all my life, since the age of 3 or 4 years old. This meant that for many years, my dharma path was a solitary one, led by books.

It was beyond me to travel anywhere to receive teachings, especially not a long-haul flight to India. It was beyond me to simply be in public places or in groups. Sometimes I couldn’t leave my room. So I had to just muddle along on my own.

When did you learn meditation?

I taught myself to meditate. I started what was a pretence of meditation as a young kid, but it wasn’t very effective. I had no idea how to really meditate. At the age of nineteen (1988), I encountered some teachings on meditation and applied them. At that time, I had my first intense experiences, experiences that woke me to the total impermanence of all things and gave me a taste of profound bliss. I also had something of a visionary experience. I didn’t know what to do with the bliss or the vision, so I just left them alone. The realization of impermanence, however, had a deep and lasting impact on me.

As I had no guidance, the deep reality of impermanence worsened my pre-existing anxiety and panic. I could not see what I see now, that impermanence is beautiful and liberating. All I could see was the inevitability of death, the looming loss of everyone and everything I loved. The certainty and unpredictability of death haunted me on a daily basis and triggered my panic.

How did you deal with that worsening anxiety and panic?

I was referred to a psychiatrist by my family doctor. That was a completely useless endeavour. Then over the years, I saw three or four psychologists. I found that kind of therapy comforting in a mundane way, but it didn’t help me much at all. I also tried a number of medications, none of those worked either. Some of them made my anxiety much worse.

It took decades before I could finally get a handle on my emotional turbulence. In the end, it was Buddhist practice that freed me from anxiety, panic and compulsive thought. I got to the point where I’d just had enough with it. I finally decided I could no longer live with that level of daily suffering, and so I applied what I knew about the dharma to my difficult emotions. I embraced the true nature of those emotions and, like wisps of mist on a dawn breeze, they just evaporated. Now I have no anxiety, no panic, and no OCD. I have what I think are normal stress levels, normal everyday concerns that everyone has, but no chronic, self-perpetuating and debilitating anxiety or panic. Now that I see how effective this practice is, I regret not having done it much sooner.

Looking back on it, I can see that I had developed the belief that anxiety and panic were inherent parts of my personality, irremovable aspects of my identity. This was reinforced by the western psychological model about the self, about personhood, that it is lasting and inherent. I didn’t believe I could ever be free of the anxiety and panic. The best I could hope for was to manage it.

Of course, I was ignoring one of those core beliefs I’d long held that alerted me to the fact that I was a Buddhist – the fact that all things are devoid of separate, lasting, intrinsic self-nature. A rookie mistake but a mistake many of us who suffer greatly make, especially those of us who have mental health issues or chronic medical conditions. Once I accepted the empty, impermanent nature of those emotions, I was able to work with them.

Where did you learn to embrace the true nature of the emotions?

I certainly didn’t come up with the idea myself. It’s an ancient Buddhist practice to embrace the true nature of experience. The idea is part of the Mahamudra and Dzogchen teachings of Vajrayana Buddhism. The idea of embracing the true nature of my experience had been with me since the mid-1980s when, somehow, a hand-made booklet of one of Dudjom Rinpoche’s Dzogchen texts came into my possession. Someone had typed up one of these teachings and turned it into a little book. I found it in a second-hand store inside another book about Buddhism and bought it. I think I paid 20 cents.

It’s a miracle that this teaching made its way to me in conservative Toowoomba. That was the first time I saw Dudjom Rinpoche’s name. Although I’d read this Dzogchen teaching in the 1980s, it did not occur to me to apply it to my anxiety and panic until a few years ago, around 2016. When I decided to do so, it was astonishing how quickly and effortlessly it worked. A debilitating complex of conditions I’d had all my life (four decades) was suddenly gone.

Which text of Dudjom Rinpoche’s was it?

I think it was Dudjom Rinpoche’s Calling the Lama from Afar. At some point in the early 1990s, I loaned that little Dzogchen-infused booklet to someone and that someone never returned it. I eventually lost touch with them and so will never get it back. Luckily, I found this text online a few years ago and finding it again was what inspired me to use it on my anxiety and panic. If the text I found online isn’t the exact same teaching, the words of the two verses that helped me with my anxiety and panic are almost identical. Once I knew for sure that it was an authentic teaching by Dudjom Rinpoche, I felt confident using it to free myself of my lifelong misery.

This method is what you share in some of your workshops?

Yes. I founded Jalu Buddhist Meditation Centre with my partner Martin Jamyang Tenphel to share practical dharma with those in need. In Buddhism sharing dharma is considered the ultimate act of generosity. Generosity is the first of the paramitas, and the most perfect generosity is the giving of the priceless gift of dharma. As I understand it, the Buddha encouraged us to give dharma according to our capacity, which I interpret as helping those like ourselves, with similar problems and at a similar point on the path.

This is a kind of peer-to-peer instruction that is very democratic, though recognizing that someone who has been on the path for say 20 years is likely to have more understanding than someone who has been on the path mere weeks. In Vajrayana, only those who are realized (enlightened) can teach the tantric methods, as it is easy to lead people astray. With simple meditation and mindfulness, however, we can all share the dharma according to our capacity. But, we shouldn’t see ourselves as “gurus” or even teachers, just dharma friends. As for Dzogchen, which despite being taught in a Vajrayana context, is actually a separate and distinct approach, everyone is qualified to practise Dzogchen based on their own true nature, their Buddha-nature.

Any risks associated with Dzogchen practice are ameliorated by contemplating emptiness and impermanence as preliminaries, especially the emptiness of the mind and self, and by an enthusiastic and deep commitment to Buddhist ethics and compassion. There are really only two practices in the Dzogchen schema, Trekchod and Togyal. Those practices are not what informs my process for dealing with disturbing emotions, which I call A.W.A.K.E.N. It is just the Dzogchen view that informs A.W.A.K.E.N. The Dzogchen view is everyone’s birthright. It was in the spirit of giving that I developed my own way of systematically applying the Dzogchen view to difficult emotions.

After I began to apply A.W.A.K.E.N. I came across American counsellor and dharma instructor Tara Brach’s R.A.I.N protocol and was surprised at the similarities. It fascinates me that two people disconnected by time and space can come up with quite similar approaches to the same problem simply by applying the view or philosophy of Buddhism. Despite the similarities, there are some significant differences between my process and R.A.I.N. My process is deeply and unashamedly Buddhist and relies completely on the idea that the true nature of our disturbing emotions is the pristine and perfect nature of mind (rigpa).

Can you give us a brief sense of what A.W.A.K.E.N is about, about how you overcame your anxiety?

All I did was apply what Dudjom Rinpoche taught, that’s all. The Dzogchen teaching of Dudjom Rinpoche’s that I was fortunate to encounter is not directly about disturbing emotions, but there are a couple of verses about the true nature of experience and the true nature of mind. They are:

The primordial ground of self-awareness is unmoving and unchanging.

The Dharmakaya’s efflorescence of whatever arises is neither good nor bad.

Since awareness of Nowness is the real Buddha: by openness and contentment, we find the Lama in our heart.

When we realize that this unending Natural Mind is the very nature of the Lama, there is no need for attached and grasping prayers or artificial complaints.

By relaxing in uncontrived Awareness, the free and open natural state, we obtain the blessings of aimless self-liberation of whatever arises.

When you take that view of the true nature of experience and of reality and apply it to working with disturbing emotions, it has the result of allowing those emotions to dissipate before they fully take shape. This is what Dudjom Rinpoche called the “aimless self-liberation of whatever arises.” A pleasant side effect of the process is an experience of joy.

It was not years and years of retreat and doing complicated visualizations and chanting mantras that freed me of my disturbing emotions. It was a very simple, easy and direct practice of just connecting with the true nature of mind and the true nature of the illusory display we call our world. That practice was contained in just a few lines of teaching from a perfectly realized being, Dudjom Rinpoche. I have taken those few lines and developed a step by step process for contemplating the true nature of reality (impermanent and empty) and a method for connecting with our mind’s true nature in a way that works with disturbing emotions.

Backtracking a little, you said that you were not able to travel for teachings, does that mean that all your dharma knowledge came from books?

At first, yes, it was all from books. It was a decade or so on from my initial discovery that I was already a Buddhist before books about Vajrayana started to appear in Australia. At first, a rare few, then a seeming rush. By the 1990s, I had more than enough to read, contemplate and apply.

By that point, the 1990s, I had already been a Buddhist for two decades, albeit not a particularly hard-working or capable one. I was also managing my anxiety and panic well enough that I could occasionally go to teachings. I was also able to finally go to university, many years later than I should have. My anxiety and panic still surfaced regularly, making life and study difficult, until I finally applied the A.W.A.K.E.N protocol.

To this date, I can almost count the number of teachings I’ve attended on just two hands. For the last couple of decades, I have corresponded with a number of lamas, getting practice advice in that way rather than through public teachings or joining groups. The teachings I have pursued relate to my early visionary experiences, which I needed to place in context and understand.

That early experience was about the subtle or spiritual architecture of the body and also the bardos, the intermediate states we experience from moment to moment and between life and death. For example, in order to understand those early experiences, I’ve received teachings from a number of lamas on phowa, the transference of consciousness at the time of death. I’ve also sought and received teaching in chöd, the practice of severance, of cutting our ties to the self and its fears and entanglements. I sought empowerment and teaching in the Dudjom tradition of chöd, hoping it would help me with my anxiety and panic, which it certainly did. Without a doubt, though, it was the Dzogchen view that finally freed me from that burden.

Interestingly, now that I am free of anxiety, panic and OCD I can travel to any teachings I want but I don’t feel the desire to do so. I am happy just doing my simple practice, which is meditation and embracing and resting in the true nature of my experience. Not that I have accomplished this, I’m just practicing at it. Practice is what we do until we achieve realization. Once we attain true realisation, practice is no longer necessary. Until I am fully liberated I will do my practice, and also seek the advice of lamas I admire about that practice and about the dharma in general.

As well as the workshops on dealing with disturbing emotions, you also lead Buddhist’ reading retreats’, can you tell me a little about those?

Because my own path has been one in which books and reading have been at the heart of everything, it is only natural that I should make reading a part of how I share dharma. A reading retreat brings practitioners together to read and discuss the same book. These retreats can be done both in a retreat place, where everyone comes together, or using online technology. Although attendees doing an online retreat aren’t in the same location for the retreat, they are asked to make a commitment to spend the weekend reflectively, not engaging with all the hullabaloo of daily life.

The reading retreat, online or at a retreat place, is an opportunity to have a proper break from routine and read, relax, focus and reflect. Generally, I choose the book, although I take recommendations. I like books that are both a concise introduction to Buddhism and a good introduction to the wonder of innate awareness that is revealed through meditation. During the retreat, I give talks to provide context or help with comprehending the material and provide exercises and reflections the attendees can do during their personal time. It is a simple idea, but it is a great way to share dharma and be part of a Buddhist community.

In terms of being a part of a Buddhist community, which teachers do you rely on for spiritual guidance?

As the Buddha himself encouraged, I turn to the dharma as my teacher, meaning two things: Firstly, that I use the things of existence itself (dharmas), life and reality, to ground me in an understanding of impermanence and emptiness; and secondly, that my first port of call for authoritative teachings are the early sutras, the Heart Sutra in particular. In terms of living teachers, I have deep admiration for Ngakpa Karma Lhundup Rinpoche, who is a great example of humility, compassion and knowledge. Karma Rinpoche is recognized as an incarnation of one of Do Khyentse Yeshe Dorje’s close students. Do Khyentse was well-known for his eccentric way of living and teaching.

I have recently also made a connection with Namgyal Dawa Rinpoche, one of Dudjom Rinpoche’s grandsons and the recognized incarnation of one of Dudjom Rinpoche’s most important teachers. We have a very modern relationship, relying mostly on social media contact. He is a great example of boundless, un-biased love. He is also a great example of humility, fidelity to lineage and devotion. There are a number of women teachers I also deeply admire, the main one being Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo.

Last but by no means least, one of my most important teachers is my partner and Jalü centre Co-Director, Martin Jamyang Tenphel. He is an example of practice despite significant adversity and of the profound insights that can come through simple meditation and devotion. Jamyang has a deep understanding of the emptiness of the self and its labels. He doesn’t identify with any labels at all. He has also taught me how it feels to be unconditionally loved. That is a profound and important teaching. All sentient beings should know what it feels like to be truly loved.

Thank you for answering my questions. Is there anything else you’d like to share with the readers?

Only this:

All we have to do is apply the dharma to our daily lives, just apply the fundamental teaching in a sincere way. We don’t have to travel here and there for hundreds of empowerments and teachings. We just need to apply the teachings we have. We don’t even need to get those teachings in person, though that can be wonderful, we can get them through reading and contemplating authentic dharma in books, or even watching online videos of true masters.

You can connect with this vast and beautiful tradition of Buddhism where you are right now. You don’t need to go anywhere. Your enlightenment isn’t in Asia. It’s with you right now. You don’t need to change the outer shape of your life or adopt Asian customs.

The heart of Buddhism is your own compassionate nature, which is ever present and undimmed no matter what your individual circumstances are. Time and place, culture and race, gender and sexuality, these things make no difference to your potential. Just connect with your own compassionate nature, your true nature. That is the heart of Buddhist practice.

For me, Buddhist practice is not about outer activities like pilgrimage or hanging out at temples or joining dharma groups, though all those things are great. It’s about turning inward to the sanctity and perfection that is already there. I would also like to encourage anyone reading this to abstain from harming others, both our fellow humans and our animal friends.

All beings deserve kindness, and we should be the source of that kindness. Not only that, as Buddhists, we should be active in stopping the ongoing decimation of our natural environment and the cruel treatment and murder of animals. We can easily lessen the suffering of animals by being vegan or vegetarian or at least reducing our meat consumption. That is all.

Connect with Pema Duddul

Website: https://jalumeditation.org

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/JaluMeditation

More articles by this author

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Jess Stewart

Author | Buddha Weekly

Jess is a freelance writer and qualified high school teacher in English. She is also currently studying a Master of Arts in Librarianship. She is a member of no less than four writers’ groups and writes micro-fiction in her spare time. Jess hails originally from Oregon but now lives in Sydney, Australia, where she moved to take advantage of the near constant sunshine.