Zen Style: The Ritual Aesthetics of Seated Meditation

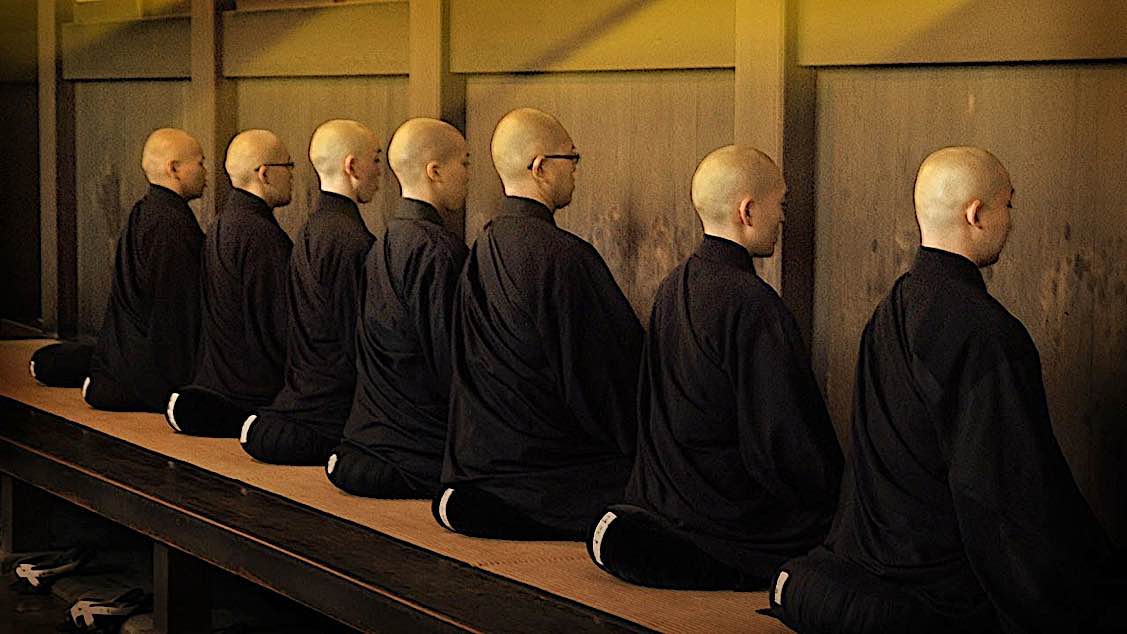

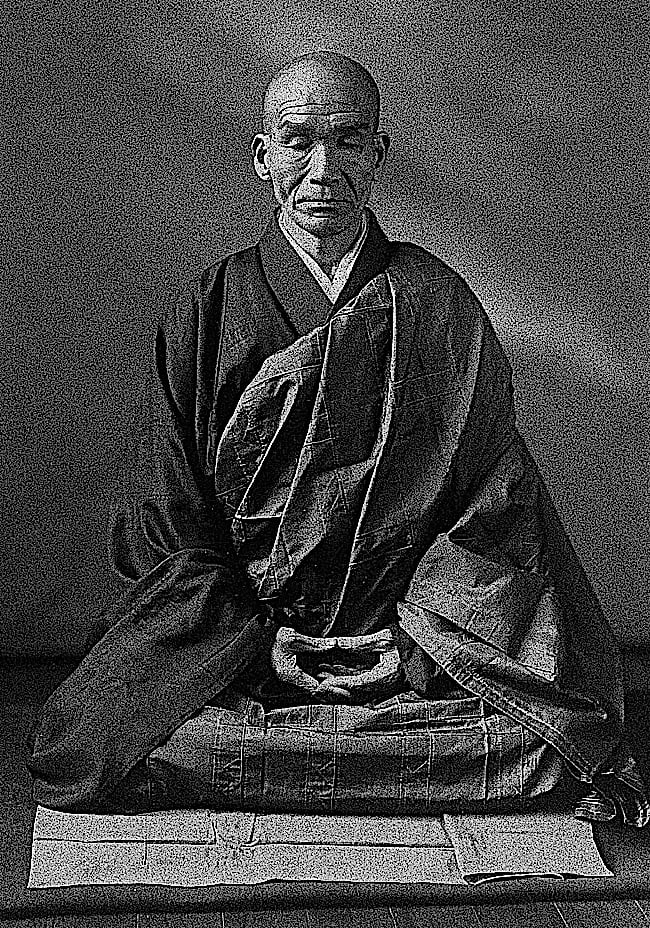

Zazen is sublime. It is a performed image of balance, symmetry and harmony.

By Henry Blanke

Author Opinion Feature

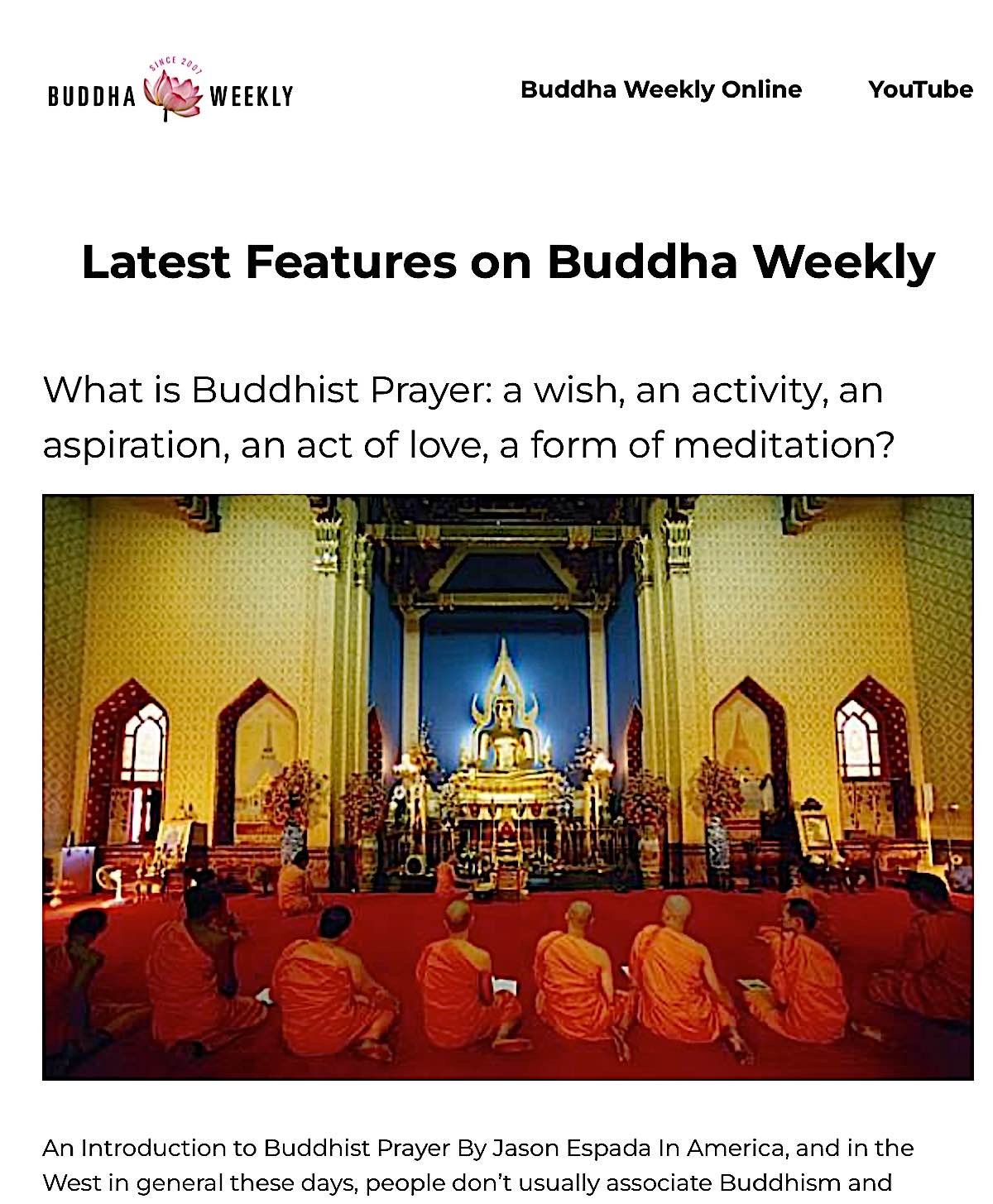

The Zen school takes its name from the Japanese word for meditation and no one prioritized zazen more than Eihei Dogen, the 13th century founder of the Soto sect. According to him zazen is a ritual enactment and expression of the activity of awakened awareness (intrinsic enlightenment).

The other major Zen sect, Rinzai, generally emphasizes zazen as a means to achieve an experiential breakthrough which instantiates enlightenment. In practice, this approach treats awakening as a state to be achieved via the technique of koan introspection. Contrarily, in his Dharma discourses to the monks in his monastery Eihei-ji Dogen emphasizes over and over that the zazen he teaches (transmitted to him in China by Chan masters of the Caodong school) is not an instrumental means-to-an-end praxis, but rather the ritualized enactment of ongoing enlightenment. [1] In this way, it is akin to the arts which are practiced and enjoyed not for their utilitarian function, but for their intrinsic aesthetic value.

One of Dogen’s fundamental points is the unity of practice and realization: one does not sit in zazen to attain a future enlightened state (“make a buddha”), but because Buddhahood is already and always manifest and zazen is the vital function of buddhas, bodhisattvas, ancestors and all practitioners. [2] Also, Dogen stresses that zazen is a communal ritual — not a solitary practice– in which all monks sit together “when the assembly is sitting” in zazen and stop together when its time for sleep. “Standing out has no benefit; being different than others is not our conduct.” [3]

That zazen for Dogen is an enacted ritual is made clear in one of his primary meditation manuals, Fukanzengi (Universal Recommendation of Zazen). Here he provides detailed instructions on preparation of the meditation space, proper posture, leg and hand placement, head alignment etc. “Sit either in the full or half lotus position …. Then place your right hand on your left leg and your left hand on your right palm, thumb tips lightly touching [this is the hokkai-join or cosmic mudra] …. Align your ears with your shoulders and your nose with your navel.” [4] This is similar to the ritual hand gestures (mudras) and yogic postures of Vajrayana Buddhism or the stylized symbolic hand and finger movements of Indian classical dance. In Bendowa, an earlier text intended to introduce Japanese Buddhists to seated meditation, Dogen writes: “When one displays the Buddha mudra with one’s whole body and mind, sitting upright in this samadhi even for a short time, everything in the entire dharma world becomes buddha mudra, and all space in the universe completely becomes enlightenment.” [5]

Dogen’s zazen can be seen as a ritualized aesthetic performance which actualizes realization. And in Zen body and mind form a continuum so that physical posture and and mental states are inseparable. It should be emphasized again that Dogen repeatedly states that zazen is not a skill one can master in order to attain enlightenment. “The way is originally perfect and all-pervading. How could it be contingent on practice and realization? …. What need is there for special effort? …. Indeed, the whole body is free from dust. Who could believe in means to brush it clean?” And later in the text he writes: “The zazen I speak of is not a meditation practice [technique]. It is simply the Dharma gate of joy and ease.” Awakening is not a matter of effort and mastery, but is joyful and all-pervasive. [6]

Zazen is a beautiful practice. Sitting upright, still and quiet with others and not engaging in discursive thought, but simply being can be transformative.

And, according to renowned 20th century Soto Zen master Kodo Sawaki, it is “useless” in that it is not a technique to gain spiritual insight, psychological well-being, self-improvement or any other goal. [7] This runs counter to the consumerist self-help obsessions of contemporary American society. Over the last 50 years or so Zen has been established as an alternative spiritual practice and many have gravitated to it for its perceived lack of ritual formality. But, as this essay has shown, the method of seated meditation promulgated by Soto Zen founder Dogen is a ritual enactment of (and is inseparable from) enlightenment. In fact, he sought to ritualize every activity of the daily life of the monks at his monastery. This included a prescribed comportment for cooking, cleaning, tooth brushing, toilet use as well as the manner in which his Dharma discourses were imparted and received. [8] However, zazen was the focal ritual and remained so as Dogen’s successors spread Soto Zen throughout Japan.

Many young people in the Unites States, following the Beat Generation, gravitated to Zen because they viewed it as being unencumbered by the stilted ritual formality which had disillusioned with them the institutional Judeo-Christianity they were brought up in. And contemporary American culture as a whole seems averse to any kind of ritual. But now in Zen centers across the country there is plenty of ritual employing candles, incense, chanting, gongs, bells and such. However, a deeper understanding of seated meditation itself, not as a means to attain enlightenment, but as an aesthetically refined ritual performance of intrinsic enlightened awareness would be salutary.

Notes and Citations

- Leighton, Taigen Dan; Okumura, Shohaku (2010). Dogen’s Extensive Record: A Translation of the Eihei Koroku. Wisdom Publications.

- Tanahashi, Kazuaki (1995). Moon in a Dewdrop. North Point Press.

- Leighton; Okumura n. 1

- Bielefeldt, Carl (1988). Dogen’s Manuals of Zen Meditation. University of California Press.

- Uchiyama, Kosho; Okumura, Shohaku; Leighton, Taigen Dan (1997). The Wholehearted Way: A Translation of Eihei Dogen’s Bendowa. Tuttle Publishing.

- Bielefeldt (n. 3).

- Sawaki, Kodo; Okumura, Shokaku (2014). The Zen Teachings of Homeless Kodo. Wisdom Publications.

- Leighton, Taigen Dan; Okumura, Shohaku (1995). Dogen’s Pure Standards for the Zen Community. State University of New York Press.

Author Bio

Henry Blanke is a Soto Zen Buddhist who began practice in 1983 as a student of Bernie Glassman’s at the Zen Community of New York. Most recently he was a member of the Ordinary Mind Zendo where Barry Magid teaches. His writing on Buddhism has appeared in Speculative Non-Buddhism, Religious Socialism and the Tattooed Buddha. Henry now resides in New Orleans, Louisiana.

More articles by this author

Search

Latest Features

Please support the "Spread the Dharma" mission as one of our heroic Dharma Supporting Members, or with a one-time donation.

Please Help Support the “Spread the Dharma” Mission!

Be a part of the noble mission as a supporting member or a patron, or a volunteer contributor of content.

The power of Dharma to help sentient beings, in part, lies in ensuring access to Buddha’s precious Dharma — the mission of Buddha Weekly. We can’t do it without you!

A non-profit association since 2007, Buddha Weekly published many feature articles, videos, and, podcasts. Please consider supporting the mission to preserve and “Spread the Dharma." Your support as either a patron or a supporting member helps defray the high costs of producing quality Dharma content. Thank you! Learn more here, or become one of our super karma heroes on Patreon.

Henry Blanke

Author | Buddha Weekly

Henry Blanke is a Soto Zen Buddhist who began practice in 1983 as a student of Bernie Glassman's at the Zen Community of New York. Most recently he was a member of the Ordinary Mind Zendo where Barry Magid teaches. His writing on Buddhism has appeared in Speculative Non-Buddhism, Religious Socialism and the Tattooed Buddha. Henry now resides in New Orleans, Louisiana.